First, some background: As a Wisconsin legislator I was one of the people who sued the state in 2011, arguing that maps drawn by my Republican colleagues amounted to an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander.

It was the case that prompted the Supreme Court to decide last year that federal courts have no role in refereeing such disputes — setting the stage for another set of partisan brawls across the country next year, over the contours of congressional and legislative districts for the rest of the decade.

This week the Republicans retained their solid hold on the Legislature, so they will have the power to unilaterally take the first shot at drawing the new Wisconsin maps. Then the Democratic governor, Tony Evers, will have the power to reject those maps.

In the middle stands the People's Map Commission, created by the governor this year to come up with new lines "free from partisan bias and partisan advantage." The nine people have no authority, but Evers hopes their work becomes a compromise acceptable to him and the GOP lawmakers in Madison. If he's wrong, the stalemate would be broken by maps drawn by the conservative-leaning state Supreme Court.

Here is my proposal for the commission, one that would give us fairer and more competitive districts — two of the chief goals for those of us who want to ban gerrymandering from Wisconsin.

Unlike the so-called Iowa Model, which a lot of "good government" groups in Wisconsin favor, my proposal requires using the data about how people in specific districts have voted over the past four or five presidential or gubernatorial elections. It also would allow for disregarding some municipal and county lines and some communities of interest.

I propose these changes because there's no other way to get to politically competitive districts in Wisconsin.

Such competition is important for the preservation of democracy. If one party gerrymanders its majority into a perpetually dominant position, that seriously erodes public confidence in our democracy and creates doubt that elections mean anything.

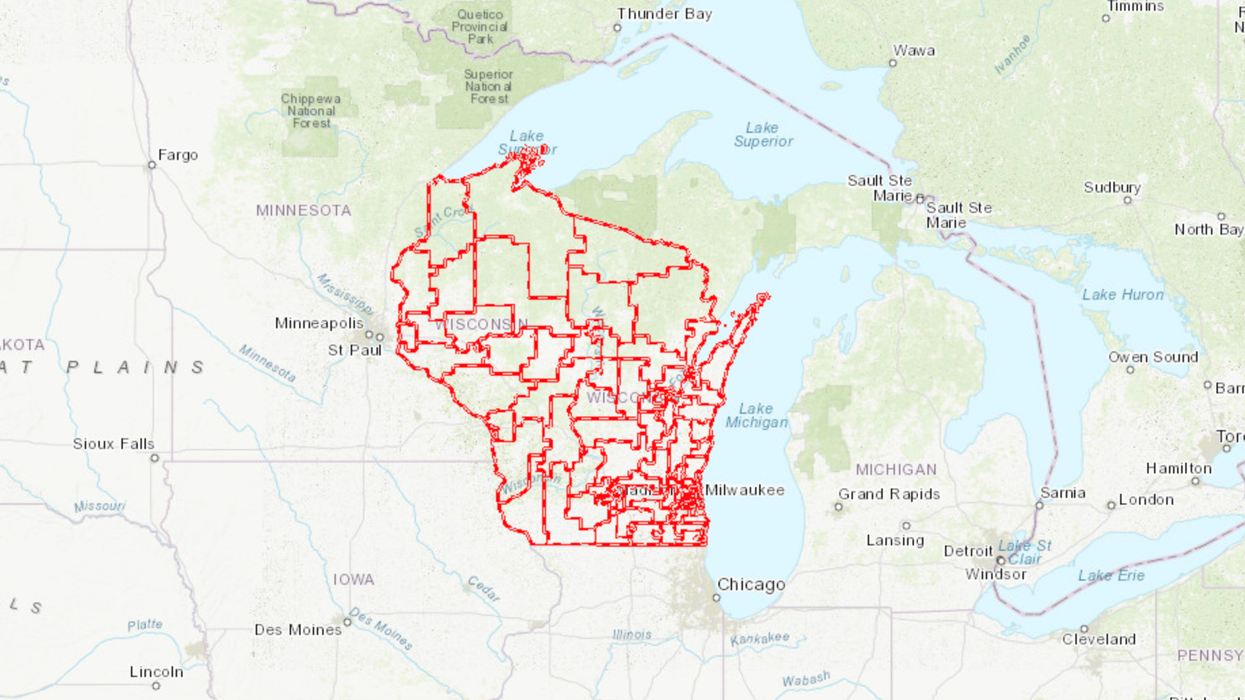

Any map where a majority of districts could be viably contested by both Republicans and Democrats would be impossible under the single-member district plan that Wisconsin has now — because too many people live in areas of Republican concentration, and too many in places of Democratic concentration.

But that doesn't mean we can't have more districts that are competitive. My view is that a fair map should require at least 10 percent of the total districts to be competitive between the parties, meaning the difference between red and blue voting base is below 2.5 percent. Both parties should have a shot at the majority of the seats in a close election, and particularly if it's a landslide. Another 5 percent of districts should be drawn so the difference is below 5 percent.

Since the redistricting is done after the census details are finalized, the votes for both presidential candidates this fall can be combined with statewide totals from all the other elections in the past decade — then averaged to determine the state's partisan balance. Results through 2018 show we are an almost exactly evenly divided state.

It is essential to reflect partisan election voting patterns when constructing a fair map because without this data, you'd be drawing blind.

If you want to achieve equal balance you also may have to stretch and violate the rule against crossing county and municipal lines in order to achieve the ultimate goal of fairness. An outlandish and irregular shape should never be adopted.

You also may have to bend the "community of interest" standard, which is the plague of the redistricting efforts and has exacerbated the excessive partisanship that has occurred in the past 20 years.

Too much focus on keeping like-minded communities of interest in a single district reduces competition too much. It breeds ideologues in both parties' extremes. When a legislator does not have a general election opponent with the potential to win, that lawmakers fears only a primary challenge. This results in the election of too many who fear that compromise will lead to their defeat. This is why bipartisan solutions for major issues are so elusive.

In the 2011 redistricting, Republicans removed African Americans voters from any marginal districts in both houses of the Legislature. The effect was to silence the voices and lower the influence of many Black lawmakers in Madison.

It is essential that a substantial number of districts have populations of both white people and racial minorities, urban and suburban dwellers, or metro area and rural residents. That is what would compel legislators to compromise or at least consider bipartisan solutions.

Drawing maps with an emphasis on promoting partisan competition, and the consensus-focused politics it yields, would do more than make the Legislature more responsive to Wisconsin's challenges. Equally important, it would achieve citizen confidence in the process and affirm that democracy exists at the state level.