This is the fourth of four parts in an exclusive weekly series of articles in The Fulcrum by J.H. Snider on Alaska’s 2022 periodic constitutional convention referendum. Part I describes the spending spree over the referendum. Part II proposes a deterrence theory to help explain the extraordinary amount the no side spent. Part III describes the failure of the referendum’s marketplace for campaign finance disclosures. Part IV provides recommended reforms to fix this broken marketplace.

The legitimacy of constitutional democracy should depend in part on the ability of a people (the “constituent power”) to initiate higher lawmaking without seeking approval from government officials created by a constitution (the “constituted powers”) who have an intrinsic conflict of interest when given power to determine their own powers. That is, constituent power should include a meaningful right for the people to not only ratify but initiate and propose constitutional changes independently of the constituted powers, including the legislature.

If groups with concentrated benefits have effective veto power over calling a constitutional convention, such power conflicts with the democratic norms of both political equality in general and constitutional democracy in particular.

The higher lawmaking power to initiate and propose constitutional change is conferred in 18 states by the constitutional initiative and in 14 by the periodic constitutional convention referendum. Many groups like the former while hating the latter because the former gives them substantial constitutional agenda control whereas the latter does not. As for legislatures, they are the natural enemy of both types of constitutional bypass mechanisms.

The democratic reform community should oppose any threat to the reasonable exercise of constituent power at the initiation and proposal stages of constitution-making. That should include not only creating undue barriers to placing a constitutional initiative on the ballot, such as barriers to gathering signatures, but also undue barriers to calling a constitutional convention, such as disproportionate and obscene expenditures by one side in a debate over calling a convention. Such expenditures give one side an unfair and undemocratic advantage not only for current but also future convention election cycles.

For calling a convention, I suggest that the no-to-yes-expenditure-ratio be viewed as an indicator of a failed political marketplace. For example, a ratio of 78 to 1 should be viewed as not only a clear indicator of such failure but also that convention referendums in general are an extreme case of such failure. With the vast majority of referendums, yes expenditures are either higher or at least comparable in size to no expenditures.

One explanation for such extreme no-to-yes-ratios for convention referendums is that the great majority of ballot measures require a well-organized, well-resourced entity such as a legislature or petition champion to get on the ballot. The sponsor won’t place an item on the ballot if it doesn’t think it has the will and resources to fight expected opposition to its proposal. In contrast, a periodic convention referendum is mandated by a constitution and thus has no such sponsor at the starting gate. Winning a powerful sponsor then becomes difficult because a convention can offer no selective incentives with adequate certainty to such a sponsor in comparison to working on a well-targeted and tightly controlled constitutional amendment via the legislature or an initiative. Thus, a convention becomes a public good with the collective action problems that plague public goods.

If it were constitutionally feasible, I’d recommend banning all group contributions to periodic convention campaigns. But a series of U.S. Supreme Court cases during recent decades ruled that such a ban would be an unconstitutional breach of the First Amendment. A competing standard, now constitutionally irrelevant, was stated in Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990): “the corrosive and distorting effects of immense aggregations of wealth that are accumulated with the help of the corporate form and that have little or no correlation to the public’s support for the corporation’s political ideas….”

Fortunately, fixing access, loophole, and enforcement flaws in campaign finance disclosure laws remains constitutional. On access, ballots should include links to campaign finance disclosures for the yes and no positions on a convention referendum, with an exemption for small individual contributions. The purpose of campaign finance disclosure is to provide a helpful voting cue to voters and making that cue more accessible would further that goal.

This would provide a better cue than Alaska currently provides via its ballot pamphlet. For the 2022 convention referendum, Alaska’s Lt. Governor recruited the head of a fringe party with 3% support among registered voters to write the position favoring a convention, which he then mailed to all Alaskans. The no campaign then touted that person and his extremist positions as the face of the yes campaign.

Effectively implementing this proposal would be difficult, as illustrated by the abysmal interface of Alaska’s disclosure database, which is like wading through old-fashioned handwritten checkbooks with a separate checkbook report for each day’s entries. This information pigsty is why many people go to Open Secrets to access such data.

Illustrating a common loophole, a union in Rhode Island skirted the disclosure laws by giving funds for organizational expenses to allied groups that didn’t need to file campaign finance disclosures despite serving as the no campaign’s public face. In Alaska, two major loopholes were that the vast majority of contributed money was dark money and that group funding sources could be hidden for crucial months by having vendors take on “debt” on a group’s behalf.

On enforcement, Hawaii and Rhode Island election authorities winked at major campaign finance disclosure violations even before an election.

Civil society remedies might be more practical than public policy ones. At the local level, democratic reformers should attempt to reduce the expenditure gap between convention yes and no campaigns. At the national level, they should foster a community of both scholarly and practitioner experts on convention politics, policy, and law.

Existing practitioner organizations such as FairVote, Open Primaries, and the Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy illustrate what’s needed. For much of the 20th century, the National Municipal League served such a role. Indeed, Alaska's constitution, including its periodic convention referendum provision, closely followed the League’s model constitution.

Given the degree of current opposition and ignorance, there needs to be a commitment to making a sustained, long-term investment while tolerating short-term defeat. But given current democratic dysfunction, the ultimate payoff should be viewed as potentially large. This would require that the public be convinced that a state convention would be part of the solution rather than problem—something that convention opponents, including America’s best political talent, have invested countless millions of dollars convincing the public otherwise.

Convention opponents are correct that the convention process has significant problems. But, as democratic reformers know, that is also true of our ordinary lawmaking systems. For not only ordinary but also higher lawmaking systems, the solution to democratic deficiencies should be to fix, not abandon, democracy. Democratic reformers have been far too focused on fixing America’s ordinary rather than higher lawmaking systems. The result is that our higher lawmaking systems are now in greatest need of repair.

J.H. Snider, the president of iSolon.org, is the editor of The State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse, which provides summary information about the 14 U.S. states with a periodic constitutional convention referendum. He also edits separate websites, such as The Alaska State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse, for each state that has a convention referendum on its ballot. Snider has a PhD in American Government from Northwestern University and been a fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, the American Political Science Association, and New America.

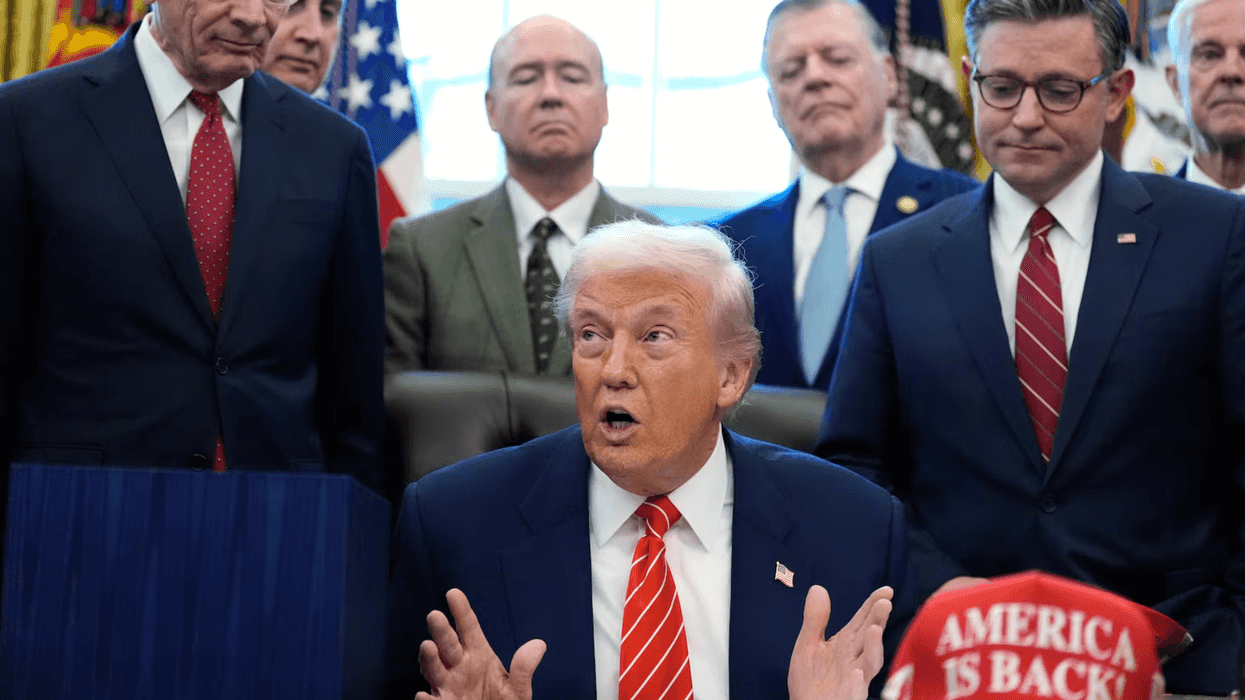

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room