Just three Republican senators have declared their intent to vote in favor of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, completing a slide toward extreme partisanship on Supreme Court confirmations that began during George W. Bush’s presidency.

In recent days, Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski and Mitt Romney have announced they will support Jackson’s nomination, drawing the ire from some fellow Republicans. That level of support is in line with the limited number of Democrats who voted to confirm Donald Trump’s three nominees to the court.

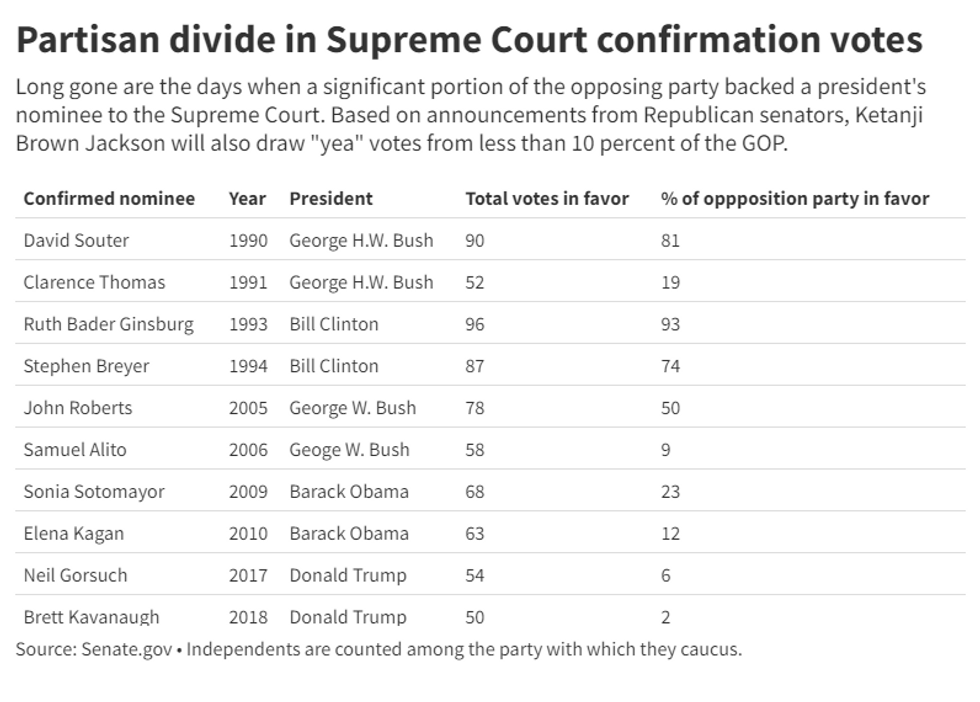

But through the 1990s, it was more common for the opposition party to back nominees. That pattern began to shift in 2005, when only half of Democratic senators voted to confirm John Roberts as chief justice.

Three of the four justices appointed prior to Roberts each received the support of at least three-quarters of the sitting president’s opposing party. Ruth Bader Ginsburg established the high-water mark in 1993, when 93 percent of Republicans voted to confirm her.

The outlier during that era was Clarence Thomas, who received just 19 percent of Democratic support following contentious confirmation hearings in which he was accused of sexual harassment. In fact, the 52 total votes in his favor were the fewest for a confirmed nominee since Sherman Minton garnered just 48 votes (but was opposed by only 16 senators).

Despite the acrimony in the Thomas confirmation, Republicans continued to generally support Democratic nominees, backing Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer during Bill Clinton’s presidency.

But then things began to change. After Roberts was supported by half of Democratic senators, Samuel Alito performed even worse in 2006, getting just four votes from the Democrats.

Republicans returned the favor during Barack Obama’s administration, providing limited support for Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Polarization has hit a new low since the Trump presidency, with barely any Democrats supporting Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh when they were nominated, and zero Democrats voting for Amy Coney Barrett in 2020.

“Increasingly partisan confirmation fights are another manifestation of more polarized parties. Starting in the late 1970s, the two parties began sorting themselves ideologically," said Keith Allred, executive director of the National Institute for Civic Discourse. "Without the mix of conservatives, moderates and liberals that used to be in each party, both parties are now more beholden to the most extreme views of their most fervent members. Presidents feel more pressure to nominate judges who will please their base and senators in the opposing party have greater incentives to please their base with more strident opposition.”

Jennifer McCoy, a professor political science at Georgia State University, agreed with Allred's assessment that confirmation voters reflect broader polarization.

"Unfortunately this pattern in confirmations follows the general of pernicious polarization in the U.S., by which I mean that the society is divided into two mutually distrustful and immoveable blocs, in an Us vs Them contest with zero-sum views," she said. "Because Republicans, as the minority party at the moment in the Senate, view any win for the Democrats or for President Biden as a loss for them, they seek to deny those wins. This produces a politics of obstruction, rather than solving problems."

McCoy further explained that structural changes are needed to reverse this slide into polarization.

"I believe we need institutional change, particularly to break the rigid binary party system holding democracy hostage in the U.S.," she said. "Reforms to increase voter choice and representation, such as ranked-choice voting with multimember districts, could begin to attenuate the vicious logic of pernicious polarization."

Allred, on the other hand, believes bipartisan cooperation can help heal the divide.

“Going forward, presidents and the most moderate senators in the opposing party will need to work together even more to nominate individuals who can attract bipartisan support and then confirm them if we’re to have more dignified and substantive confirmations than we’re currently seeing,” he said.

No Supreme Court nominee has been rejected by the Senate since Robert Bork in 1987, Harriet Miers asked George W. Bush to pull her nomination in 2005 (leading to Alito being put forward). And Obama’s final nominee, Merrick Garland was never considered by the Republican-controlled Senate – perhaps further poisoning any hope of bipartisan support for future nominees.