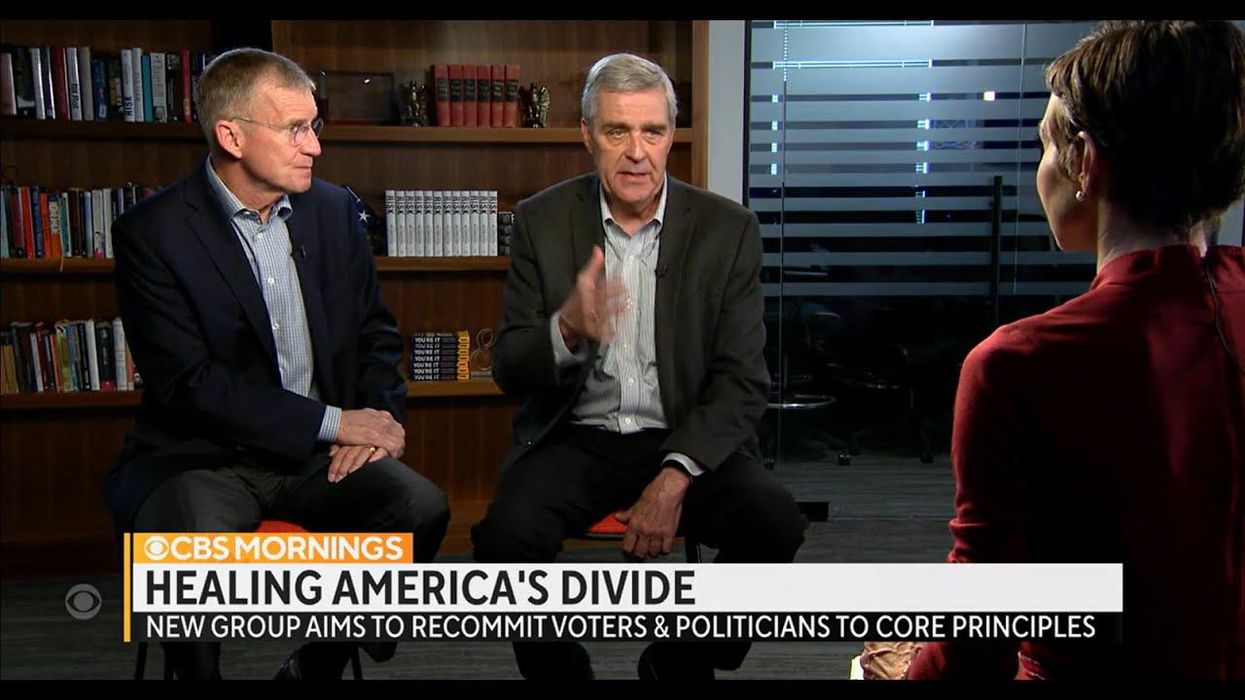

In an interview with CBS Mornings senior national security and intelligence correspondent Catherine Herridge which aired on CBS Mornings, Former Ambassador to NATO Lt. General Doug Lute (USA, Ret.) and General Stan McChrystal (USA, Ret.) publicly endorsed the Safe and Fair Elections (SAFE) Pledge created by the non-profit Team Democracy.

Video: Team Democracy Urges Citizens to Sign SAFE Pledge

Team Democracy Urges Citizens to Sign SAFE Pledge (CBS)