Hans Zeiger is president of the Jack Miller Center ( www.jackmillercenter.org), a nationwide network of scholars and teachers who are committed to advancing the core texts and ideas of the American political tradition.

Recently, I was on a cross-country flight when someone was having a medical emergency in the back of the plane. A flight attendant spoke up over the loudspeaker, asking that anyone on board with medical training hit their call button. Well, there happened to be quite a number of nurses on board that flight—they were heading to the national nursing convention in Philadelphia. One after another, chimes rang out in chorus. Call it what you will, a cacophony of professionalism, mixed with a spirit of volunteerism, the sound of men and women who had committed their lives to caring for people like the person who was in need on that airplane. Everyone who pushed their call button that day felt some obligation to do so, and the person in the back of the plane received the care they needed.

We see this spirit in the men and women who commit their lives to service in the uniform of the armed services, to first responders in every community, to teachers, nonprofit board members, city council members and school board members, charitable donors, neighborhood watch organizers, Little League coaches and scout leaders—the list goes on. We see this spirit in countless moms and dads, and grandmas and grandpas, who sacrifice for their families and do everything they can to pass along a legacy to the next generation. These kinds of human connections, borne of obligation, can happen anywhere in the world, but in America they have a particular role to play in our national story.

Yet when it comes to our narrative about ourselves, we tend to emphasize rights far more than obligations.

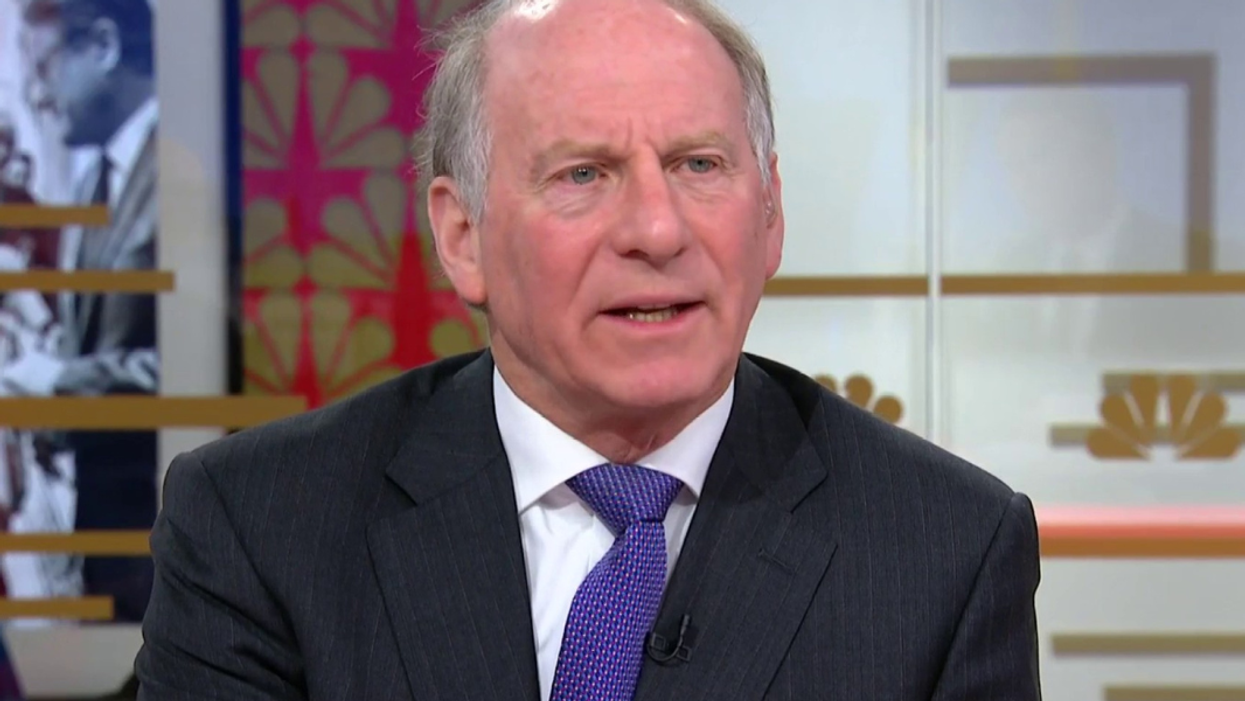

In the face of declining trust in our public institutions and a waning sense of shared identity as fellow citizens, Council on Foreign Relations President Richard Haass says that Americans need to recover a sense of obligation. This is the central argument of his new book The Bill of Obligations: The Ten Habits of Good Citizens.

It is no surprise that Haass has devoted most of his prolific writing career to foreign policy. It is noteworthy that he has turned his attention to American civic life at a moment when internal disunity threatens America’s standing in the world. The Bill of Obligations is a useful treatment of the subject that makes for a quick and easy read.

Haass calls out Americans’ obsession with rights in our political discourse without a commensurate focus on obligations, which he defines as voluntary commitments “involving not what citizens must do but what they should do.”

Haass is not the first to decry our obsession with rights at the expense of civic commitments—one prominent writer on the subject is Harvard legal scholar Mary Ann Glendon, whose 1993 book, Rights Talk: The Impoverishment of Political Discourse exposed the inadequacy of public debate centered on rights. Haass’s contribution to this literature comes at a moment in our political history when we can surely benefit from a reinvigoration of enlightened patriotism.

In laying the groundwork for his list of obligations, Haass describes the nation’s current state of political dysfunction and division. He worries about a loss of “common identity” among Americans. He writes, “It is increasingly hard to speak of a shared American experience, outlook, values, or priorities.”

When it comes to Haass’s list of ten obligations, there is much to admire. He celebrates values like civility, compromise, norms, and a respect for the common good. Haass does well to name “Be Informed” as the first obligation of a citizen and to emphasize the importance of understanding the foundational texts and ideas of republicanism. Being informed is not just about keeping up with the latest headlines; it requires a common body of knowledge about the nation and its institutions. This points to the importance of another obligation on Haass’s list: that of supporting civic education.

Haass’s concept of public good includes a strong dependence on private character. To keep the hope of America alive, he says, “more than anything else” we need “an abundance of character, what in earlier times was known as virtue.” If anything is lacking in Haaas’s book, it is an extended elaboration on why we must devote ourselves to the cultivation of virtue. It is a point that deserves exploration when too few public intellectuals even acknowledge it at all.

Moreover, Haass only scratches the surface when it comes to voluntarism as a component of active citizenship. He recognizes the importance of respecting one another, becoming active in political and government activities, and caring for our neighbors. More could be written on the neighborly activities that are so fundamental to the vitality of American civil society: daily support for individuals and families around us, charitable giving, and active membership in local associations, service organizations, and congregations.

Some readers may take issue with particular policy illustrations that Haass uses to describe his list of obligations—but in doing this, Haass demonstrates an independence of viewpoint that will appeal in turns to readers on the left and the right.

Haass’s book may not be an exhaustive treatment of the subject, but it is a worthy conversation-starter. America needs more public conversation and debate about the proper role of obligations, and we need more emphasis on duties alongside rights in our teaching of American civics. Perhaps most poignantly, The Bill of Obligations should be a reminder to its readers of their own obligations in our beloved republic, and of how, like the nurses on that recent cross-country flight, we might each do our part.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift