Everything about this year's election season has been exceptional, so it comes as no surprise that the plans for monitoring Election Day are without precedent.

On the day before the big day, members of the Election Protection Coalition, which includes many prominent civil rights groups, and the Voter Protection Program, which includes attorneys general from around the country, outlined ambitious and assertive plans to make sure that people who set out to vote in person Tuesday have unfettered access to the polls and help if they encounter problems.

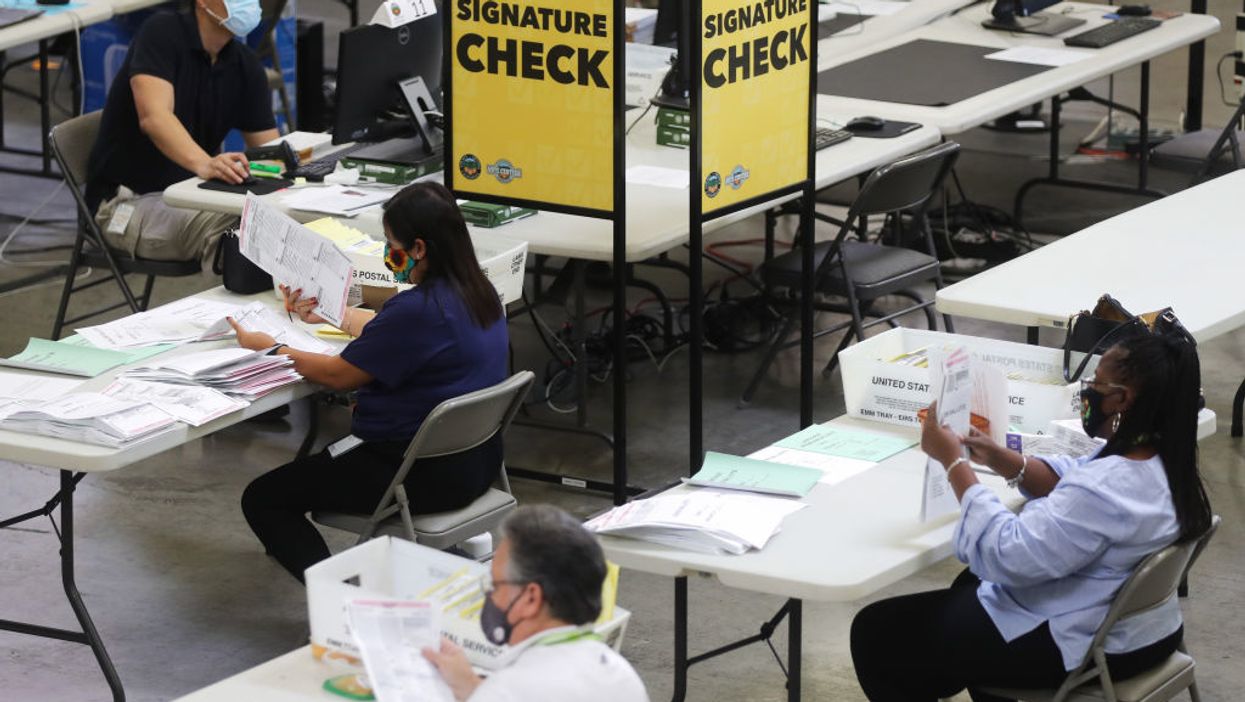

Although an astonishing 97 million votes have already been cast either by mail or in person, a consequence of intensified partisan feelings and the realities of the coronavirus pandemic, that still means 60 million ballots or more are almost certain to be cast for President Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden at polling places before all voting in the nation ends Tuesday night.

Kristen Clarke, president of the Lawyers Committee for Justice Under the Law (which leads the Election Protection Coalition), said the group's efforts are the most extensive in the 20 years it has existed.

She said the group handled about 120,000 telephone calls seeking help in casting a ballot or confronting suspected voter suppression in all of 2016 — and just in the last month has handled 135,000 such calls. And she said the number of legal volunteers it had enlisted and trained to promote a fair vote Tuesday has crested 42,000 — probably 10 times the number four years ago

So far, Clark said, the biggest volume of calls with concerns were coming from the swing states of Pennsylvania (17,800), Florida (14,900) and Texas (5,100).

Among the issues they expect to deal with Tuesday are the sorts of long lines voters have encountered in early voting states and the failure of absentee ballots that were requested to show up in people's mailboxes.

Karen Hobert Flynn, the president of Common Cause, said the venerable good government and watchdog organization organized about 6,000 volunteers to monitor the polls in 2016 and about 6,500 for the midterm 2018 election. This year's total is seven times that many — about 45,000.

In addition, several thousand volunteers will be monitoring social media for misinformation.

Maya Berry, executive director of the Arab American Institute, said proof that the disinformation campaigns have worked are polls that find two-thirds of voters worried their ballot will be counted. Despite the fear, she said, "Voter excitement has been something profound."

For those who have a problem voting, the coalition hotline is 866-OUR-VOTE (866-687-8683).

On their call, the attorneys general and other officials from the battleground states of Michigan, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Arizona and Texas condemned any attempts to threaten or intimidate voters on Tuesday. They all expressed confidence that the election process would be safe and secure, but said if any problems did arise, they would be prepared to take swift action.

At the same time, the Justice Department announced it will be sending staff Tuesday to monitor for federal election law violations in 44 jurisdictions in 18 states — ranging from the D.C. suburb of Fairfax County, Va,. to Los Angeles, and from Boston to Houston

The heightened presence of government officials and outside watchdogs comes as the nation seems on edge going into a presidential election in a way not matched in decades. Their apprehension is not only about whether Trump or Biden wins. It's also about profound concern that basic democratic foundations are wavering. Whether their vote counts, whether the loser accept the result and whether the winner will be able to at least partly repair the breach are questions on the minds of millions.

Seven in 10 voters in one of the last pre-election polls, by the Associated Press, say they are anxious about the election and the potential for violence afterward. Biden supporters were more likely than Trump voters to be nervous — by 72 percent to 61 percent.