Brogan is a volunteer attorney for American Promise.

My family and I are nearing the end of a gap year in France. One highlight of this adventure was watching the French presidential election in April in which Emanual Macron beat Marine Le Pen by a 17-point margin. As an American, it was refreshing to see how a democracy runs a presidential election without spending billions of dollars.

By law, major presidential candidates in France may not spend more than 22.5 million Euros (about $25 million) on their campaigns. We in the United States have no such limits.

Joe Biden spent $1.6 billion to win the 2020 presidential election. That is 70 times more than Macron spent on his bid, yet the U.S. population is just five times larger than France’s. There is no end in sight to the amount of money in American politics. Biden spent three times more than Hilary Clinton did in 2016. One could argue that the high stakes in the 2020 election justified big spending, but that argument applies equally to France in 2022 when there is a war raging on two NATO borders to its east. The only reason France spends orders of magnitude less than the United States in its elections is because the French have limits.

Not only does French law limit the total amount a presidential candidate may raise and spend, the government reimburses nearly half (47.5 percent) of campaign expenditures. That means only half of election funding comes from private donors. The cap on the amount an individual can donate is larger in France (4,600 Euros), but in the United States wealthy individual donors can easily circumvent our $2,900 cap by making unlimited contributions to political action committees and parties that support their candidate.

In the United States, it is perfectly legal for corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts of money to support a candidate. In France, corporate and trade union contributions are illegal. The U.S., like France, has disclosure requirements so the public can see who is funding campaigns, but there is a gaping loophole in U.S law due to our tolerance of corporate donations. Ultra-wealthy donors quickly learned to hide contributions behind the veil of political purpose nonprofit corporations known as 501(c)(4)s, which do not have to disclose their donors – so-called dark money. We simply do not know who is funding many campaigns and political causes in the United States.

Why la difference in these approaches to money and politics? France and the U.S. share the same democratic values. The principles of the French Republic etched above every government building – liberté, égalité, fraternité – are the French version of our founding values of liberty and equality with a dash of e pluribus Unum. Our separation of powers was an idea borrowed from a Frenchman named Montesquieu. Why is the free French Republic able to control campaign spending, when such limits are deemed unconstitutional in America?

Two major news stories circulating when we arrived in France expose the lie behind the reason why America cannot regulate big money in elections. The first story concerned a scandal from the 2012 presidential election in France. In September 2021, former President Nicholas Sarkozy was sentenced to a year of home confinement. His crime? Spending too much on his election campaign. To add insult, it was an election he lost to Francois Holland.

The other story was the mass protests against the government’s Covid restrictions. French citizens have the right to protest their government, just like Americans. Free speech is an essential component of la liberté. In America we have the First Amendment; in France, they have the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. These stories, taken together, prove that a democracy can have limits on money in politics and free speech at the same time.

Over the past 40 years, while France and other democracies in Western Europe have adopted stricter campaign spending limits, the U.S. Supreme Court has taken America in the opposite direction by severely limiting lawmakers’ ability to set such limits. The court’s rationale is that money is speech and limits on money in our democracy, for any reason other than to prevent the crime of bribery, violate the First Amendment’s free speech clause. When I read the Sarkozy story alongside images of citizens exercising their free speech rights on the streets of Paris, I saw just how wrong the Supreme Court is on this issue.

Recently, the court in FEC v. Ted Cruz for Senate doubled down on its long-standing position. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts struck down a limitation on donors paying off a winning candidate’s personal loans to their campaign – a practice long-considered a high risk for influence peddling – because it had “the impermissible objective of simply limiting the amount of money in politics.” In other words, the court does not care if our political system is awash in money and gives wealthy people an advantage over ordinary voters. We have free speech! Yet, as France proves, limiting money in politics and free speech are not mutually exclusive.

French law handles the conflict between speech and money by striking a balance between the democratic values of la liberte and la equalite. One value is not more important than the other. The French believe strongly that candidates and citizens have a right to speak to voters – $25 million is not nothing – but they believe just as strongly in creating as level a playing field as possible for candidates and ideas. Money creates an advantage, so it must be limited. The U.S. Supreme Court, by contrast, believes that liberty under the free speech clause trumps an equal opportunity for candidates or ideas in our political system. Roberts explicitly rejected the concept of a level playing field in a 2014 case that opened the floodgates to unlimited contributions from individuals to political parties and PACs, writing: “No matter how desirable it may seem, it is not an acceptable governmental objective to ‘level the playing field,’ or to ‘level electoral opportunities’ or ‘equaliz[e] the financial resources of candidates.’”

The court’s decades-long perversion of the First Amendment’s free speech clause gives Americans with the most money a constitutionally sanctioned advantage in our political system. As a result, America is now a plutocracy – a government run by the wealthy. Most of the money in our elections comes from less than half of 1 percent of the population, a majority of whom reside in a dozen wealthy ZIP codes. A plutocracy is not government by We the People.

An overwhelming majority of Americans think it is bad for the wealthy to have too much influence in Washington. But how can we pass laws that regulate money in politics when the Supreme Court says they are unconstitutional? There is only one answer. Amend the Constitution. Give lawmakers the power to regulate money in politics. The First Amendment would be protected, but the Supreme Court would have to balance it against the express authority given to lawmakers by the For Our Freedom Amendment to limit the amount of money in American politics.

Article V of the Constitution, covering the power to amend, gives the American people the ultimate say in how we want to be governed. It is not easy to amend the Constitution but we have done so 27 times before. The Article V process was designed to be difficult so that changes to the Constitution are made only when there is overwhelming crosspartisan support from American lawmakers and voters. Polling demonstrates such a level of agreement that money should not provide an advantage in American politics. Three-fourths of Americans, including 88 percent of Democrats and 66 percent of Republicans, support an amendment to get big money out of our politics.

Let’s harness this consensus to pass the For Our Freedom Amendment. My experience observing French politics this year convinced me that the Supreme Court is wrong. Money is not the same as speech. Money destabilizes our political system by giving candidates and ideas backed by big money an advantage. France is proof that a democracy can have both a free exchange of ideas and a level playing field.

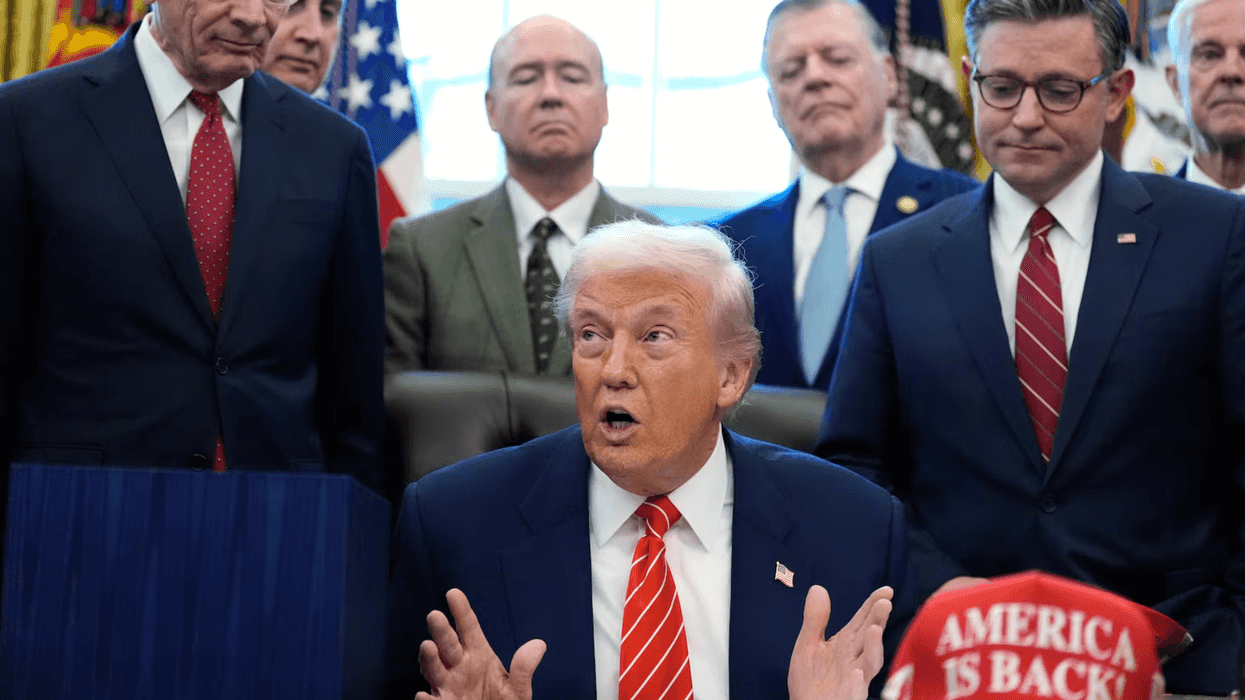

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift