Since New Mexico enacted a new disclosure law last year, more than $800,000 in political spending has been publicly reported by nonprofit groups that in the past would have remained largely hidden.

It's a change that Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver calls "a huge victory." But Austin Graham of the Campaign Legal Center, which advocates for tighter regulation of money in politics, is more reserved: "What's on the books in New Mexico is not the most cutting edge, but it's undoubtedly a big improvement from the last decade."

The New Mexico experience illustrates that improving the transparency of how campaigns are financed can be done, but making progress often requires incremental steps that take a lot of time. What has happened in New Mexico is an example of what states across the country must grapple with when they seek to slow the influence of money over their own politics, at a time when federal regulation of presidential and congressional elections has shriveled.

An ocean of money still floats through the state's elections while remaining out of public view — it's spent on mailers and advertising that blanket television, radio and social media as elections near — because the new law didn't strengthen donor disclosure requirements for political action committees.

More than $4.8 million in spending on campaigns across the state this year came from PACs whose donations are very difficult if not impossible to trace to their original source, according to an analysis by New Mexico In Depth and The Fulcrum. That's because their donors often are nonprofit groups or other PACs, so the only way to learn where the money originally came from is to find out the contributors to those other groups.

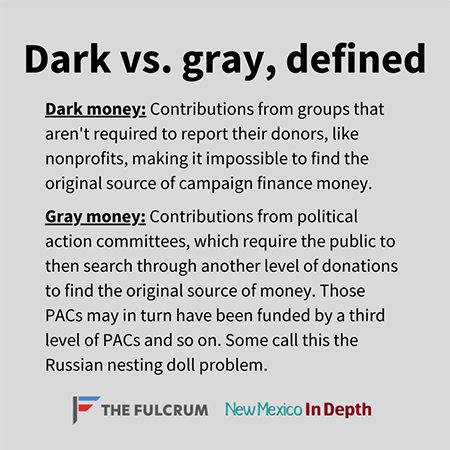

Finding out who gives to nonprofit organizations — so-called "dark money groups" — can be next to impossible, because for the most part they aren't required to identify their own donors.

But identifying who is giving to groups registered as political action committees in Santa Fe is difficult, too, it turns out. Sifting and sorting through multiple layers of public reports that PACs must file might lead to original sources of their money, but more often it comes to a dead end.

Welcome to the world of "gray money" — when PACs give to other PACs.

One salient example in New Mexico this year was the almost $1 million spent by two groups to promote a ballot measure, passed with 56 percent support, that will make the state's Public Regulation Commission an appointed rather than elected body. The Committee to Protect New Mexico Consumers reported spending $269,000 but didn't disclose its donors. Vote Yes to Reform the New Mexico PRC spent $689,600 and reported that its donors were five other groups — one based in New Mexico and the others in Washington, D.C., or New York.

Creating a system with far greater transparency about who's seeking to influence elections may be daunting, but other states have done it and offer models for drawing back the curtain on political giving. Several campaign finance experts point to California in particular. For nearly five decades, its robust campaign finance system has been successful in promoting transparency in one of the largest political spending markets in the country.

Awash in gray as well as dark money

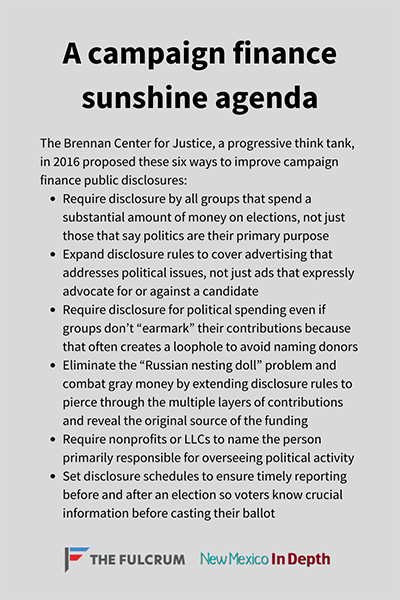

Since the Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. FEC lifted restraints a decade ago on political money spent independently of candidates, secretive spending has only become more entrenched in American elections. The Brennan Center for Justice, a liberal public policy institute at New York University Law School, found that just four years after the decision, only 29 percent of outside spending in state races across the country was transparent — plummeting from 76 percent four years before the ruling.

In a 2016 report, the center described dark and gray money as especially harmful in state elections because special interests can spend far less than they would at the federal level and still have a substantial influence on the outcome.

"For candidates used to modest budgets and low-key campaigning, dark money can prove an unfair and expensive obstacle, possibly discouraging potential candidates from deciding to compete," it concluded.

Six years ago, two-thirds of contributions to political committees nationally came from other PACs. And such gray money has only become more pervasive in state and local elections since, said Chisun Lee, one of the authors of the Brennan report.

"Gray money is a convenient and too often legal way to conceal the identity of the true giver of the money for political spending," she said. "Why wouldn't political donors take that route if they're able?"

New Mexico In Depth analyzed every contribution made to a political action committee in the state during the 2018 and 2020 campaigns, focusing on transactions of $500 or more. Based on these contributions, we identified 11 funded mostly with dark money from nonprofits and 25 that received most contributions with gray money from other PACs. All together, these PACs spent almost $13 million over the last two elections, roughly a third of all PAC expenditures in the state.

The biggest of them, the Verde Voters Fund of Conservation Voters New Mexico, paid more than $2.5 million primarily to communications and political consulting firms. But the source of the cash that came from its largest donor, the League of Conservation Voters, is permitted to remain a mystery.

Perhaps most clearly emblematic of gray money, though, is a PAC called Better Future for New Mexico, which funneled $1.6 million to other PACs operating in the state. It reported raising $2.7 million, almost entirely from three nonprofits: State Victory Action, Grove Action Fund and Civic Participation Action Fund. Two of them don't have to report their donors, and they didn't.

California goes deep on disclosure

Had those contributions been given to groups in California for political activity, those groups would have likely had to file their own reports with that state. California is seen as a model for how other states could implement disclosure laws geared toward identifying the original source of campaign finance dollars.

Even though campaigning and lobbying in the nation's most populous state is a billion-dollar industry, Sacramento has kept dark and gray money spending at bay.

California requires groups to disclose the source of the money they use to influence elections, and goes a step further by requiring donors themselves to file reports if they give generously enough.

Groups involved in elections must report donors who give $100 or more for political purposes. But when such money doesn't account for a group's entire spending in an election, it must start identifying donors whose gifts weren't earmarked for political activity — starting with the most recent, until the total donated matches the total spent.

But what combats gray money secrecy in California the most is its major donor rule.

PACs taking a gift above $5,000 must notify those donors they might be required to file their own report with the state — which they have to do once their cumulative campaign donations top $10,000. And if those major donors, in turn, have raised money to fuel their political giving, they must register as a political committee under California law and send similar disclosure notices to their own generous donors. This process continues until all the original donors are identified.

Hiding behind a corporate identity is not allowed; the $10,000 threshold combines money from individuals and businesses or groups they control. And failure to disclose the "true source" of a campaign's money can be prosecuted by the state as money laundering.

Beyond the reporting requirements, California puts donor information in front of the public when they're confronted with a political ad — in print, on social media, or on TV or radio. In some cases, the "paid for by" messages must list the sponsor's three most generous donors at $50,000 or more.

Then there is the state's Fair Political Practices Commission. Established 46 years ago in response to the Watergate scandal, the bipartisan watchdog agency is independent from the state government.

Last year the panel responded to more than 14,200 phone and email inquiries, hosted 44 workshops about state campaign finance law and resolved almost 1,500 enforcement cases, including 343 settlements that produced almost $800,000 in fines. It also has the power to set new money-in-politics rules, including one that took effect in August requiring some businesses to name the person primarily responsible for approving political activity.

"While the amount of dollars spent is an issue for some people, our main concern is that the public gets to see where the money is coming from," said Jay Wierenga, a commission spokesperson.

Making change in New Mexico

Toulouse Oliver, New Mexico's chief elections official as secretary of state, said she supports further bolstering of the state's campaign finance disclosures because it's important information for the public is making voting decisions. "It's something that I absolutely will be talking to our legislators about as we prepare for the next legislative session," she said.

The 2021 session of the Democratic-majority Legislature convenes in January for its regular annual session. But Toulouse Oliver expressed trepidation, saying she didn't want to see New Mexico's laws voided by the courts again, after a decade during which the state's Campaign Reporting Act was unenforceable. And she said a push for new rules would likely be an uphill effort.

"It's something that I anticipate having a lot of pushback on from every entity or organization that does this kind of political activity, because it will mean that they have to dedicate more resources to keeping their books straight in terms of where the money is coming from," she said.

Both the Brennan Center report and New Mexico reform advocates point to evidence the public wants greater disclosure. In a poll last year by the Campaign Legal Center, 85 percent of Democrats and 81 percent of Republicans supported changing the rules to require public disclosure of contributions to all organizations that spend money on elections — effectively ending the world of dark money. And a poll last year by Common Cause New Mexico found 94 percent support statewide for enhancing campaign finance disclosures.

But the Brennan Center report also warns that states should set reasonable parameters and not make disclosure laws unduly burdensome on the free speech rights of political groups or their benefactors.

"The idea is not to force transparency against everyone and their neighbor who is participating, but rather common-sense disclosure laws so voters can be informed about substantial donors and who is influencing public discourse," said Lee of the Brennan Center.

One possible reason that reforming New Mexico campaign finance law has taken so long is that citizen-initiated ballot measures are not allowed — so changing the rules is up to legislators, for whom ease in raising campaign money is top of mind.

Dede Feldman, who retired after 16 years as a Democratic state senator, during which she championed a law imposing campaign contribution limits, said the possibility of changing such rules presents legislators with a tough choice: Protect themselves and their odds of getting re-elected or do what's best for the public?

"When you come to power with one system, you are reluctant to give that up," she said.

Metzger is a reporting fellow at New Mexico In Depth. This story was written and edited in collaboration with that nonprofit news site.