Breslin, author of "A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation's Fundamental Law," holds the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair in Government at Skidmore College.

The Founding generation would be astonished by the Supreme Court’s abortion ruling. Not because constitutional framers like James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin gave much thought to a woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy. Let’s be honest, they didn’t. No, the revolutionary and visionary men who birthed a nation and designed the country’s federal constitution would be astounded by the high court’s impudent decision because it violated the very principle they fought so hard for – the principle that expanding liberty was the ultimate aim of a righteous polity.

The American Revolution was fought to expand liberty. Thousands of colonists perished on the battlefields of Saratoga, Breed’s Hill, Trenton, Lexington and Concord precisely in order to reclaim those rights that the British Crown had withheld. Those courageous individuals recognized that they were fighting to expand a conception of liberty that King George III so cavalierly disregarded. Indeed, the Declaration of Independence was penned by Thomas Jefferson and signed by 56 patriots so as to magnify the “unalienable” rights that the “Creator” had “endowed.” Governments, Jefferson wrote, “are instituted among men” to “secure these rights;” it was inconceivable to think otherwise.

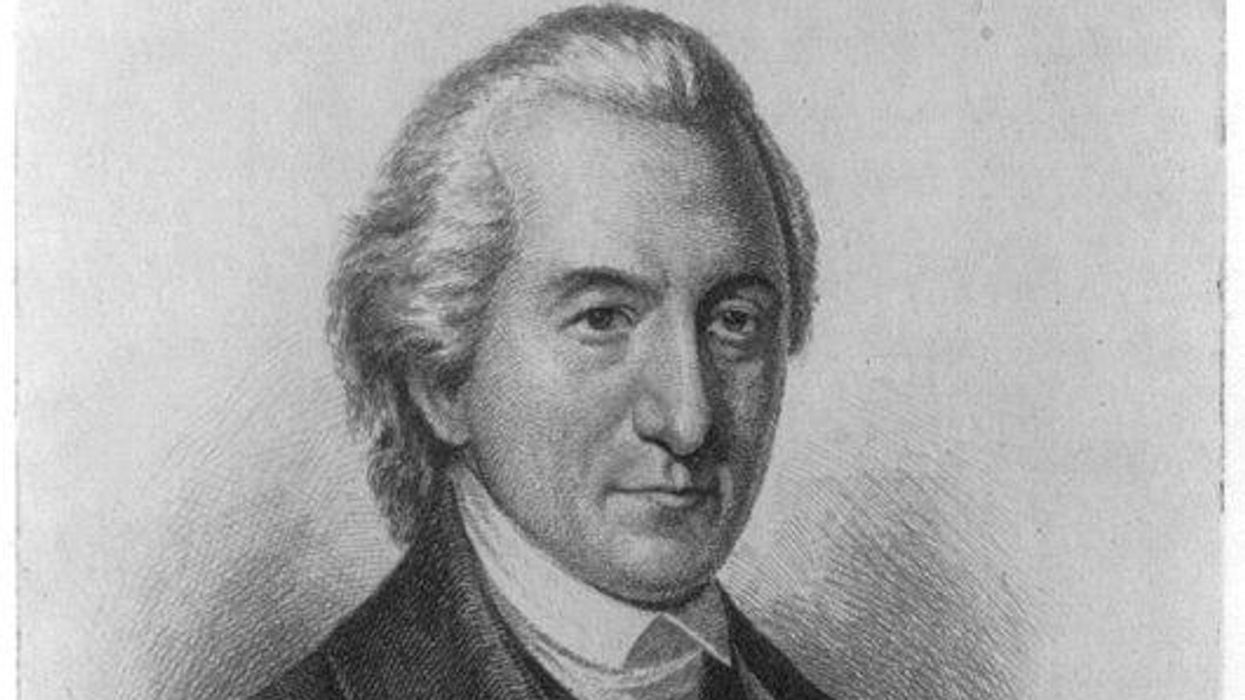

John Dickinson, one of America’s most underappreciated Founders, even drafted an early version of the Articles of Confederation in which he emphasized the significance of extending personal freedom. As a Quaker, Dickinson recognized that a Constitution is divine; it is a sacred text. But it also evolves. And the arc of that evolution, he insisted, must point towards greater freedom – the extension of rights, not the retraction of them. His sentiments resonated with an entire generation. Most newly independent Americans embraced that bedrock principle.

But perhaps the greatest evidence that the Founding generation would be shaken by the overturning of Roe v. Wade comes from the pen of Alexander Hamilton. He, you see, warned the members of the Philadelphia drafting convention and the various state ratifying conventions of the real danger associated with including a Bill of Rights in a Constitution. He wrote in “Federalist 84” that embedding a list of freedoms in the fundamental law is both redundant – “a Constitution is itself a Bill of Rights,” he argued – and potentially hazardous because no group of people could ever recognize, articulate and enumerate the entire list of safeguards humans enjoyed. There are freedoms we can’t yet conceive of, the famous New Yorker maintained; and those liberties will remain unprotected by a government that is beholden to a discreet and exclusive list.

Madison agreed. As a pragmatist, though, he also conceded that ratification of the Constitution hinged on the addition of a constitutional list of freedoms. So, what did the “father of the Constitution” do? He included the Ninth Amendment among the 17 he introduced to the First Congress. The Ninth Amendment reads, “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” In other words, Madison maintained, the list of freedoms that the founding generation has identified in 1789 cannot, and should not, be static. That list is not a fixed or settled object. Indeed, Madison, demonstrating characteristic humility, concluded that there are other rights he had yet to imagine, distinct rights that have not yet revealed themselves to any human mind. The right of privacy is one such freedom.

For Madison, Hamilton, Dickinson, Jefferson, the Anti-Federalists and so many others, the expansion of rights, not the retraction of them, was always the objective. Like most members of the Founding generation, these men acutely understood that the story of America’s development has to be a story of the amplification of freedom. The court’s decision rolling back a fundamental freedom belies that origin story.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift