Carlson is a high school science teacher in the rural farming town of Royal City, Wash., and a volunteer for RepresentUs, a nonpartisan organization that advocates for a broad array of democracy reforms.

I was blessed to be born into a family that taught and modeled conservative values. My parents and grandparents showed me — not just with their words, but with their deeds — the values of honor, integrity and heeding the wisdom of our ancestors.

These values have shaped my personal and political choices my whole life. I have always voted for the candidate who I thought best represented these values, which I will readily admit has usually led to me voting for Republicans.

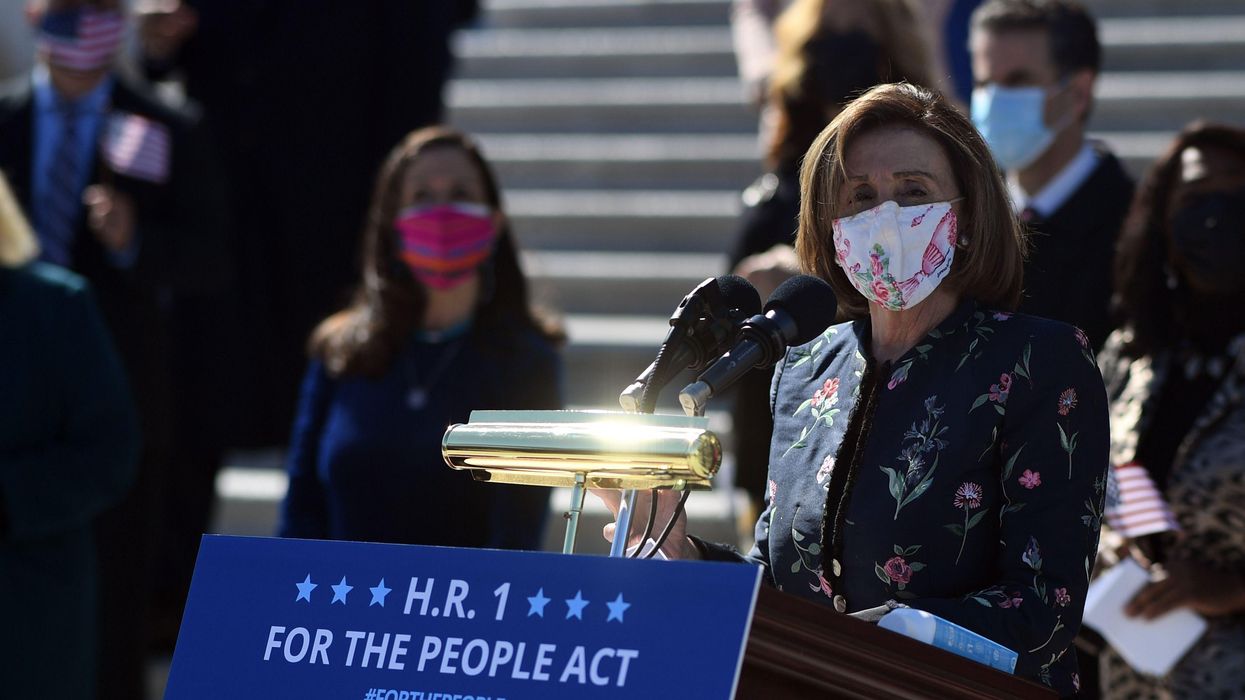

My conservative values also lead me to support the For the People Act — the comprehensive voting rights and democracy reform legislation now pending in the Senate after being passed by the Democratic-majority House, albeit without a single GOP vote.

I truly believe that conservative values make the strongest case for this bill.

Consider the conservative values of honor and integrity. Many modern politicians lack either one. This is because honor and integrity are not assets, but rather liabilities, in a system that relies on such things as partisan gerrymandering and dark money.

Gerrymandering allows the politicians in power to pick their voters, custom-drawing their own electoral districts so they can coast to re-election year after year — without honoring their commitment to represent all the people they have pledged to represent.

Dark money is the term for the ocean of cash — more than $1 billion during the 2020 campaign — that nonprofit organizations are able to spend on politics without revealing the identities of their donors. Candidates who benefit from dark money have an obvious competitive edge over those not beholden to these special interests.

Given these two advantages, is it any wonder Congress had an average 24 percent approval rating in the last year but a 90 percent re-election rate last fall?

The For the People Act (also known as HR 1 and S 1) addresses these issues by turning over the drawing of congressional districts to independent commissions instead of politicians, and by requiring trade associations, unions and other politically active nonprofits to disclose who's giving them money and what campaigns they are funding — which, incredibly, is not required right now. (The scandal, as they say, ain't what's illegal.)

Once politicians are required to actually earn the votes of those they represent — and can no longer rely on rigged districts and secret money sources to stay in power — we will see honor and integrity filter back into the institutions that were designed to represent us.

When discussing this legislation with my conservative friends and family, the single biggest objection they raise is that the bill would seize power from states and local governments and put it in the hands of a remote and bloated federal government. "What could be more sacred to the conservative values than the right of a community to manage its own affairs?" they ask.

This is a valid concern. Its resolution comes from looking through the lens of another conservative value: the wisdom of our ancestors.

States will still run their own elections. The bill sets some basic rules to protect voters and the security of our elections nationwide. History shows this balance is necessary.

Following the Revolutionary War, our country first framed a government dedicated to the principle of complete local autonomy. The outcome under the Articles of Confederation was disastrous, spurring a constitutional convention to revise and repair the system.

The wise James Madison realized that corrupt factions had a much easier time gaining control over a local government than a central government — the phenomenon that caused the collapse of the Greek democracies and the Roman Republic. He believed a strong central government would provide an important check and balance on the worst impulses of local control.

In "Vices of the Political System of the United States," Madison made this argument powerfully.

"Place three individuals in a situation wherein the interest of each depends on the voice of the others, and give to two of them an interest opposed to the rights of the third. Will the latter be secure?" he asks. "The prudence of every man would shun the danger."

He then suggests that if the number of people is expanded to 3,000, the danger would be substantially reduced, concluding: "A common interest or passion is less apt to be felt, and the requisite combinations less easy to be formed, by a great than by a small number. The society becomes broken into a greater variety of interests and pursuits of passions, which check each other."

For that reason, he and the other Framers designed a Constitution with a central government, one that has lasted over 230 years.

I have no doubt that Madison — along with Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and George Washington — would fully support enactment of the For the People Act. And while I may not agree with a number of the positions held by my state's senators, Democrats Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell, I am happy to note their support for this legislation.

Conservatives should want politicians with honor and integrity, and a government that heeds to the wisdom of our ancestors who wrote the Constitution. The For the People Act takes us in that direction. And for that reason, I call on my fellow conservatives across the country to support this bill and to encourage their senators, in both parties, to vote for its passage.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift