A long, and long-shot, quest to get more candidates onto the presidential debate stage has run aground in a federal appeals court.

The Libertarian and Green parties, and the nonprofit advocacy group Level the Playing Field, have been challenging the debate qualifications for six years, arguing they unfairly if not unconstitutionally favored the nominees of the two major parties. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals flatly and unanimously rejected all those arguments last week.

Many groups who view the political system as broken place much of the blame on the Republican and Democratic duopoly, which they say will never be weakened unless candidates with other allegiances have a shot at victory. And a prerequisite for getting a serious look for president, they argue, is getting your personality and policies known to the sort of national TV audience only debates command.

For three decades, however, the Commission on Presidential Debates has used a 15 percent national polling average threshold in deciding who is invited to the general election campaign faceoffs. The threshold is so high, critics say, that it's essentially impossible for an outsider to meet during this era of highly polarized partisan politics.

Candidates must also be on the ballot in enough states to be mathematically capable of winning a majority of electoral votes, a much simpler test to pass than the polling average.

The nonprofit commission, run by a bipartisan board, is generally bound by rules set by the Federal Election Commission. And, writing for a three-judge panel Friday, Judge Raymond Randolph concluded"there is no legal requirement that the commission make it easier for independent candidates to run for president."

The lawsuit also maintained the debate commission's membership and procedures were biased in favor of the two major parties.

"Party chairs, former elected officials, top aides, party donors and lobbyists" have almost always filled the seats on the so-called CPD, the plaintiffs argued in their brief to the appeals court. "These staunch partisans endorse Republican and Democratic candidates, lavish them with high-dollar contributions, oversee even larger contributions as paid-for-hire lobbyists and accept undisclosed contributions from corporations that buy influence with the major parties using the CPD as a conduit."

Randolph's 13-page opinion rejected that argument as well, noting that the panel is largely following the parameters set by the FEC but also reviews its rule book and considers changes after every election to see if changes need to be made.

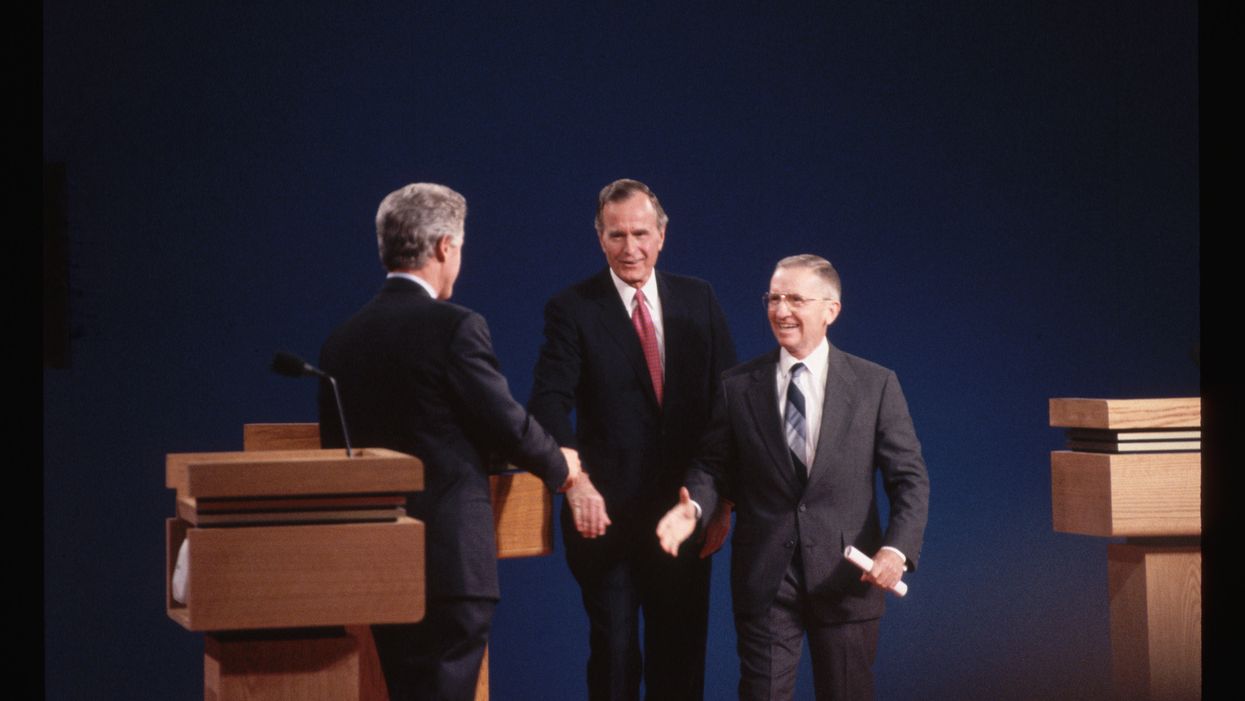

For instance, after the independent billionaire Ross Perot was excluded from the 1996 debates despite running a second nationally visible campaign, the panel adopted new criteria making the stage a bit more accessible — although not so available that anyone other than the GOP and Democratic nominees has participated in the subsequent five elections.

The same will almost certainly be true this fall, when President Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden are scheduled to meet three times and their running mates are to debate once. Libertarian Justin Amash was the most prominent third-party candidate to enter the race this year, but he ended his bid only after three weeks.

Level the Playing Field and a voter in Washington, D.C., started the case back in the fall of 2014, filing an administrative complaint with the FEC. The Greens and Libertarians joined the cause the next year, but they were unable to persuade the agency to drop public opinion polling from the debate invitation criteria.

The groups then sued in federal court, where District Judge Tanya Chutkan at first asked the FEC to reconsider and then dismissed the lawsuit altogether last year. The D.C. Circuit ruling affirmed that dismissal.