Anderson is editor of "Leveraging" and ran for the 2016 Democratic nomination in Maryland's 8th Congressional District.

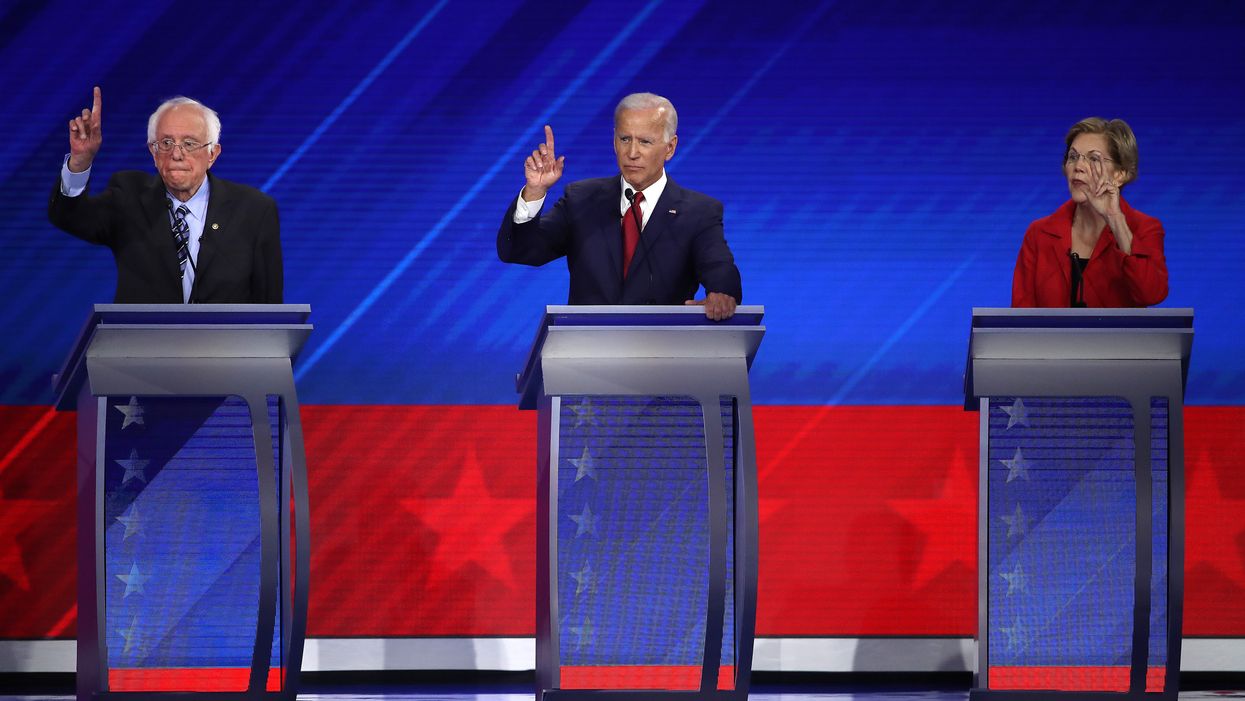

With the House impeachment inquiry officially launched, no one can predict how this will affect the race for president, especially the Democratic primary. Because the inquiry concerns allegedly impeachable acts by President Trump to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate behavior by Joe Biden when he was vice president, Biden's candidacy is now being discussed from every possible angle.

With so much attention on Biden, it is notable that the concept of centrism has received so little analysis. The pundits tell us Biden is a centrist and that Elizabeth Warren, for example, is a progressive; likewise, Amy Klobuchar is a centrist and Bernie Sanders is a progressive. And so on. Indeed, the campaign to date is regarded as a standard battle within the Democratic Party between its moderate-centrist and progressive-leftist wings.

But there are many problems with the way the internal battle has been conceptualized.

Centrists are frequently defined in terms of what they do not support. Thus centrists in the Democratic Party who are running for president don't support Medicare for All. And they don't support the Green New Deal. Instead, these centrists defend more "moderate" health care and climate change policies. This is why centrists are frequently called moderates.

The concept of centrism actually comes from the positioning our politicians have on the political spectrum. The left includes the socialists, even communists, and the right includes fascists. Toward the center you find a space for mainstream democrats. Now mainstream democrats, and this is small d and not capital D for the United States' Democratic Party, have their own spectrum. Thus those to the left of center are the progressives or welfare state liberals; those to the right are the conservative or libertarian democrats. Those in the middle are the moderates.

Almost all Democrats and Republicans in Congress, and also President Trump, fit into the center of the overall political spectrum. There are some exceptions. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, for example, is a Democratic Socialist. She is on the left of the entire spectrum and is indeed a critic of almost all Democrats and certainly all Republicans. Although Democrats like Biden get labeled as "centrists," there are members of the Republican Party, though not many, who can also be called centrists. The Republicans who are a part of the No Labels Problem-Solvers Caucus, for example, can be called centrists or certainly "moderate Republicans." A co-chairman, former Ambassador to Russia and Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman, can be considered a centrist.

There is a significant problem with how centrism is conceptualized because it invariably means either a moderate version of the Democratic Party platform, the Republican Party platform — or compromise of both. The problem is that there are some versions of centrism which aim to do more than split the difference between the two parties. This other kind of centrism, which I like to call "sentrism," seeks to create a bold synthesis of the two party platforms or positions on given policy issues. Moreover, sentrism tries to create a following by motivating citizens who reject standard left, right and centrist points of view. This following is designed not to focus on public policies alone.

A sentrist could win the Democratic nomination for president, but only by breaking free of the other centrists. Trump, in many ways, provides a model. He ran as a Republican, but created his own lane in the Republican primary.

Biden could emerge as a sentrist candidate. To do so, he would need to change his campaign from one focused on restoring order and criticizing progressives in his own party to one that embraces an exciting centrist point of view that motivates citizens. What would this sentrist point of view look like? To start, Biden would need to define himself in these terms. Tell the voters: I am not a bland moderate. Nor am I a run of the mill progressive. Although 76 years old, I am a new kind of centrist.

Biden would have to make it clear where a cross-partisan synthesis is used on a given policy; why it is a mistake to call him a moderate; how he can mobilize the millions disillusioned with politics; and why this election is about electing him and not about rejecting Trump.

In Tennessee Williams' "The Glass Menagerie" the central character Wingfield exclaims, "it's just the shank of the evening" when she is hoping to keep "the gentleman caller" in her house to bond with her shy, physically limited, daughter Laura. So too can we say that for Democratic voters, it is just the shank of the primary.

If voters are patient, they may yet see a vigorous, bold centrist candidate emerge.

The reason it matters how we categorize political positions is that the pundit world and the parties themselves now control the narrative. Millions of registered Democrats and registered independents are feeling stuck between two undesirable choices: a bland, moderate centrist and an exciting, ambitious leftist. Too many citizens don't want to risk putting a vigorous, left-wing progressive in the ring with Trump, assuming he survives impeachment. Just as many are not motivated by the safe bland moderate centrists.

Yet there is a kind of centrism that gets voters out of this choice — if only a candidate will come forth and be that kind of sentrist.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift