McIsaac is managing director of learning and experimentation at Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement.

Maybe you’re like me. When you hear a person or organization say they’re trying to “save democracy,” you can’t help but wonder, “What does that mean to you?” Or, when you hear someone’s intention to promote “unity” or “civility,” those words pull at your heartstrings but then you wonder, “Wait, are we saying the same thing?”

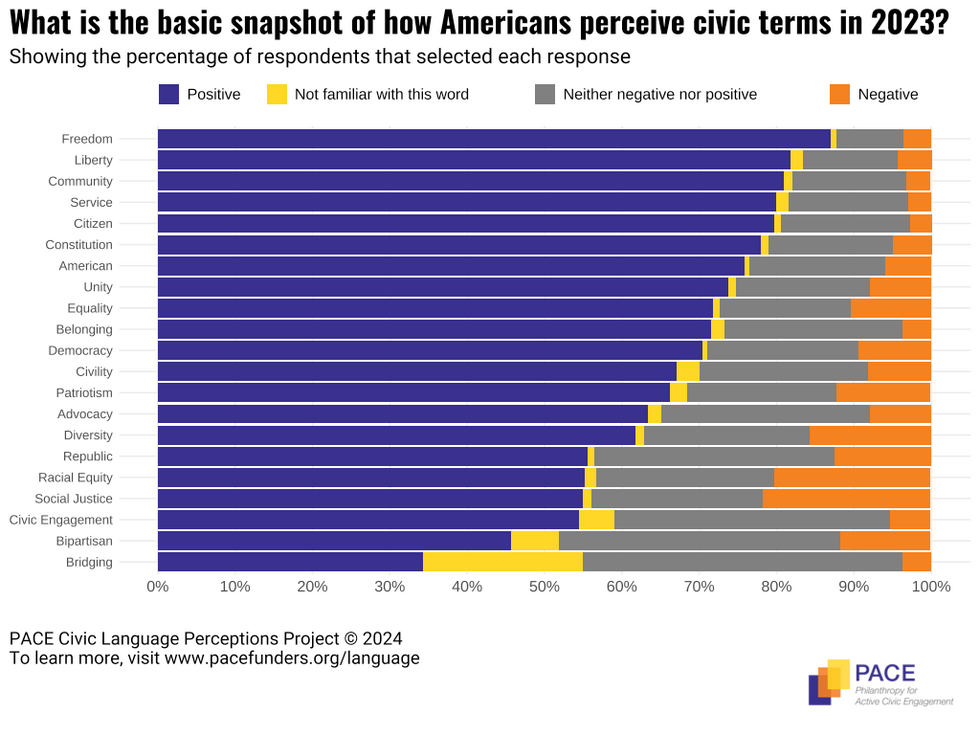

At PACE (Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement), we have spent years investigating how Americans perceive common civic terms like these, with the goal of uncovering which terms resonate most and least, and how these perceptions differ based on one’s identity and experiences. Another major purpose of the Civic Language Perception Project is to understand the degree to which civic terms are coded or loaded in ways that make them politicized – or, in other words, perceived as being favored or “owned” by political actors.

In partnership with Citizen Data, we are now releasing a new wave of data from 5,000 surveys, collected in November 2023. Our terms of interest included: democracy, freedom, patriotism, bipartisan, racial equity and diversity.

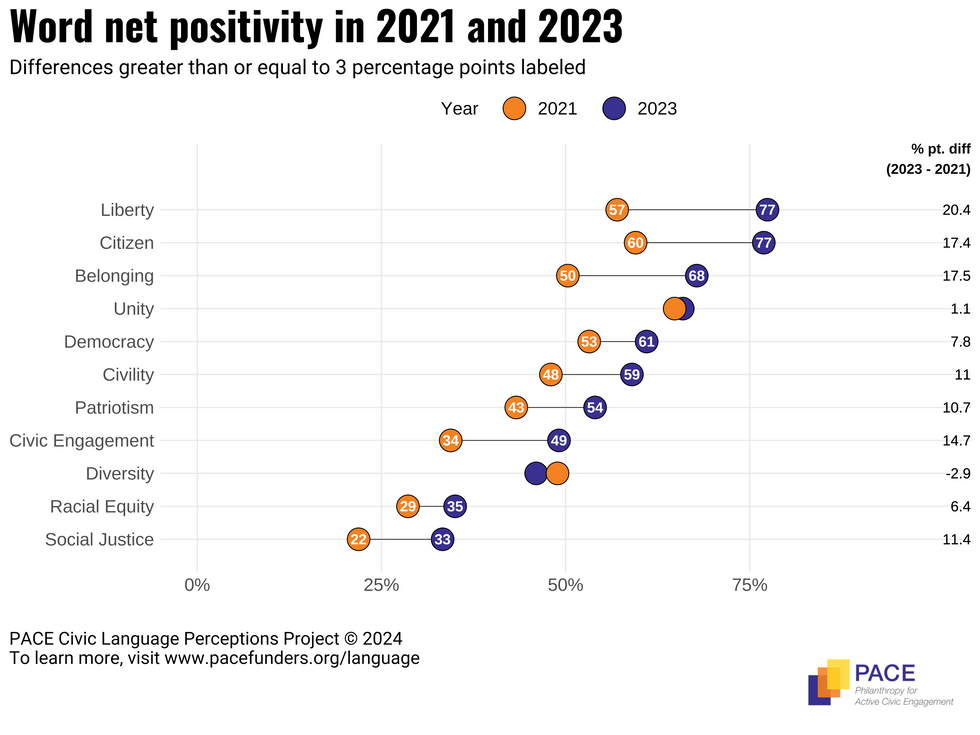

For the most part, Americans’ perceptions got more positive in two years.

Could Americans be growing tired of the language of polarizing politics, and in turn, more appreciative of civic terms? That’s one possibility behind a stunning increase in appreciation for nearly all of the terms of interest in our study – in just two years.

All terms tested in the 2023 Civic Language Perceptions Survey went up in positivity except "unity" and "diversity," though they are within or near the margin of error for the survey.

All terms tested in the 2023 Civic Language Perceptions Survey went up in positivity except "unity" and "diversity," though they are within or near the margin of error for the survey.

Another possibility might be a reconsideration of the 2021 levels. Our 2021 research surveyed people in November 2021 – not even a year after Jan. 6 and the Covid vaccine roll-out. Could Americans have been especially critical of anything having to do with democracy and civic life in 2021, therefore positioning the 2023 positivity levels as a return to normalcy? These are hypotheses at this point, and we intend to go further into our data to understand the storylines that might reveal themselves to us.

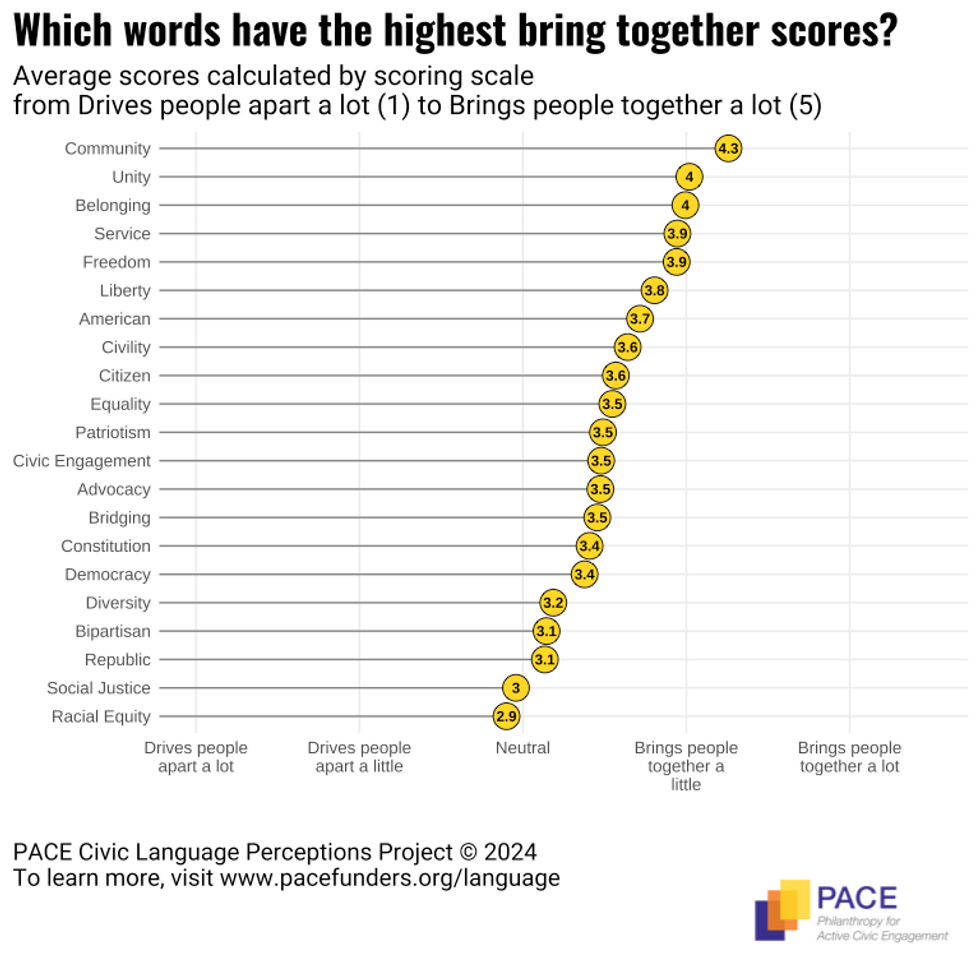

Words signaling broader values are perceived to bring people together, while jargon is perceived to drive us apart.

Political jargon has been found to be a turn off for everyday Americans, as it can send a signal that they don’t belong. This may be why terms like “bridging,” “republic,” and “civic engagement” were not perceived as bringing people together, according to our survey, earning less than 4 on a 5-point “bringing together” score.

Notably, the term “bipartisan” earned a particularly low score (just above 3 out of 5) from our survey respondents, which may reflect the opinion of some that bipartisanship is too forgiving of intolerable perspectives. Some may also be tired of the term overpromising and underdelivering.

Of course, it is also possible that survey respondents were operating with dissent bias (answering negatively, sometimes due to not understanding the question) because they simply weren’t sure what the more jargony words meant. Nevertheless, communications laypeople and professionals in civic spaces should consider when their vernacular has become “ inside baseball ” to a fault, triggering perceptions of exclusion and elitism.

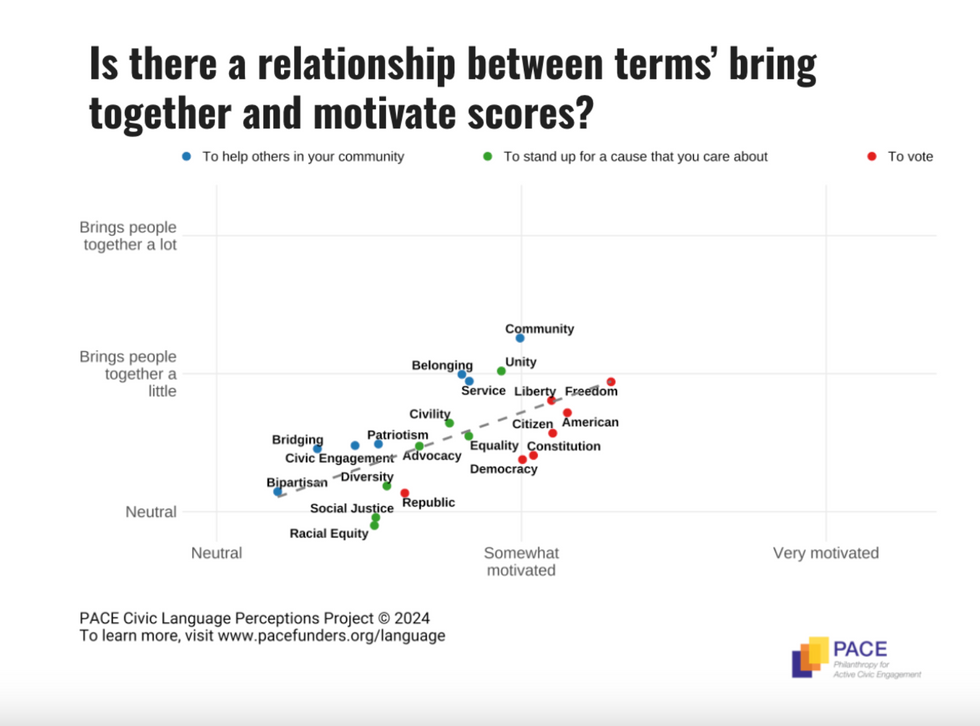

The terms Americans perceive as bringing people together also motivate them to act.

A 2018 study found that Americans donate their time more than any other nation, with over 60 million Americans – about 23 percent of the nation – volunteering 4.1 billion hours in 2021. PRRI found that about 56 percent of Americans in 2018 were “modestly” or “highly” civically or politically engaged. What motivates people to be civically engaged?

Common wisdom has taught us that people are motivated by negativity and fear. In fact, entire political and marketing strategies are built on this premise. But our data tells a different story.

Could it be that the words Americans perceive to bring people together are also the words that motivate them to action? We ran that analysis, and yes, our data confirms the trend. The more a term was perceived to bring people together, the more it was motivating Americans to action. We can't say it's a cause-and-effect relationship, of course, but we can say that there is a correlation. In fact, the correlation coefficient is 0.62, which is considered strong.

What we’re saying vs. what they’re hearing.

As a philanthropy-serving organization, we maintain a membership of funders who are each invested in strengthening democracy and civic engagement from different vantage points. One of the most common challenges we’re hearing from members (as well as others in the civic engagement space) is where people used to think they were just saying words, they now realize their audiences are hearing signals – about their political ideology, their news sources, their views of the world and more. These signals are sometimes constructive, sometimes destructive, sometimes intentional, sometimes unintentional. We often hear it this way: “The coded and loaded nature of civic terms has become unsustainable. Are there even words I can say anymore?”

On the one hand, it’s fair to say that civic terms have always been loaded, or at least fluid, in their definitions and usages. We can’t be assured that the language that is “working” for us today will have the same effect in a decade or two.

On the other hand, it’s unfair to suggest that we should therefore throw in the towel on our communications efforts and default to using whichever terms we like. As PACE’s study suggests, civic terms don’t just have the power of positive or negative perception, but can inspire positive or negative action. In our efforts to inspire voting, volunteerism, belonging, and other prosocial and procivic activities, words matter – and this includes whether they are familiar, unfamiliar, stigmatize, or embraced.