Meyers is executive editor of The Fulcrum.

Even as the partisan divide drives liberals and conservatives apart, there are certain words or ideals that continue to unite Americans, like freedom and liberty. But patriotism? Not so much.

Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement, which helps funders maximize their support for democracy-focused nonprofits, recently released a study of Americans’ perception of political terms. While many of the words and phrases have universal appeal across the ideological spectrum — the aforementioned freedom and liberty, but also others like citizen, belonging, service and Constitution — a handful performed quite differently.

“We used to think we were saying words. Now we are sending signals,” said Amy McIsaac, managing director of learning and experimentation at PACE. “‘Patriotism’ has been sending signals for a very long time.”

Nearly 90 percent of Americans have a positive reaction to “freedom,” with Democrats, independents and Republicans all above 80 percent. Similarly, “liberty” has across-the-board positive reactions. The lowest positive rating was 79 percent among Democrats, reaching as high as 87 percent among independents.

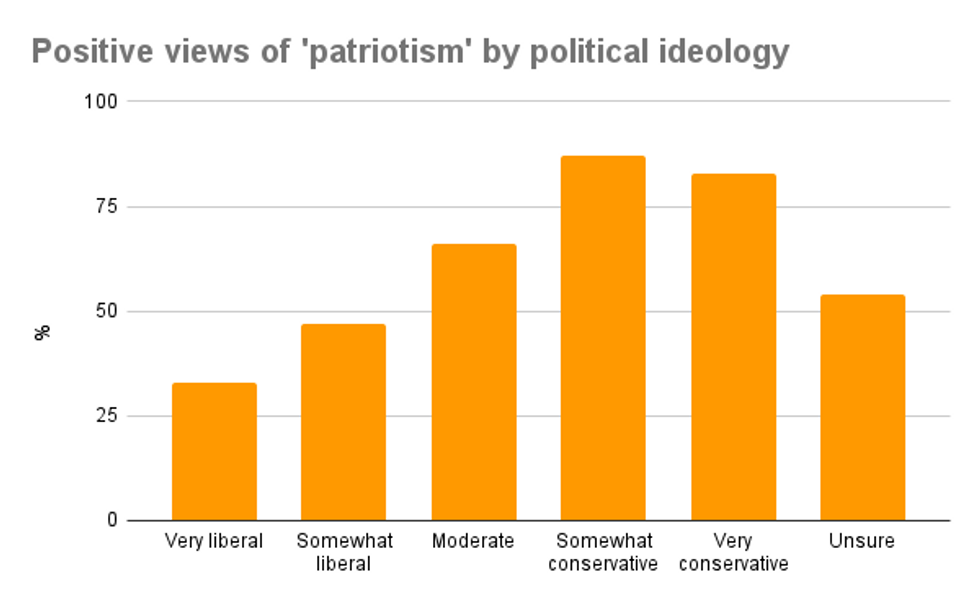

“Patriotism,” on the other hand, was only rated positive among 67 percent of respondents, with a 50-point gap among the partisan extremes: 83 percent among those who are very conservative and 33 percent among the very liberal.

Source: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement

Source: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement

And the spread between the wings has grown in recent years. PACE compared its most recent data, from 2023, to data collected in 2021. Among very conservative respondents, positive views of “patriotism” increased 12 points, from 71 percent in 2021. During that same period, positive attitudes among the very liberal decreased from 44 percent to 33 percent.

Lee Pierce, a professor of rhetorical communication at SUNY Geneseo, says these words have never really been “all-American” terms.

“These words have partisan origins that correspond with the dominant identities of conservative and liberal viewpoints. I'm not sure they've become 'more’ partisan,” Pierce said. “But there has been a significant concentration of media since the 1990s so it may be that the talking points, particularly on the right, … are more consolidated so we're seeing more frequency of fewer words. That would track with the trend toward ‘"message discipline.’"

The partisanship seems to be building on itself, according to the PACE data. Nearly three-quarters of people who identify as somewhat or very conservative said “patriotism” is fully or somewhat “meant for me.” At the other end, 44 percent of the very liberal respondents and 38 percent of somewhat liberal people said “patriotism” is somewhat or fully “meant for someone else.”

“Liberals are saying, ‘Not for me,’ and conservatives are saying, “Yep, for me,” McIsaac said.

That divide led to a striking dichotomy: “Patriotism” was both the second most positive term (after “community”) and the second most negative term (just ahead of “bipartisan”).

“Patriotism” wasn’t the only word that demonstrated a partisan divide. “Republic” is viewed far more positively among Republicans (79 percent) and Republican-leaning independents (70 percent) than among Democrats (43 percent), Democratic-leanding independents (37 percent) and independents (48 percent).

But “diversity” and “racial equity” are flipped the other way, with significantly lower positivity scores among those on the right than on the left.

Deborah Schildkraut, a political science professor at Tufts University who specializes in political psychology and racial and ethnic studies, believes there’s an element of race at play.

“In short, people’s attitudes about anything having to do with race have become more strongly associated with other political outcomes, such as vote choice,” she said. “So words have partisan connotations because people of different parties feel differently (and strongly) about the issues that those words represent. “

And then there are terms that have yet to gain a foothold, presenting a challenge — and perhaps an opportunity — for the people and organizations working to bring Americans together across the partisan divide.

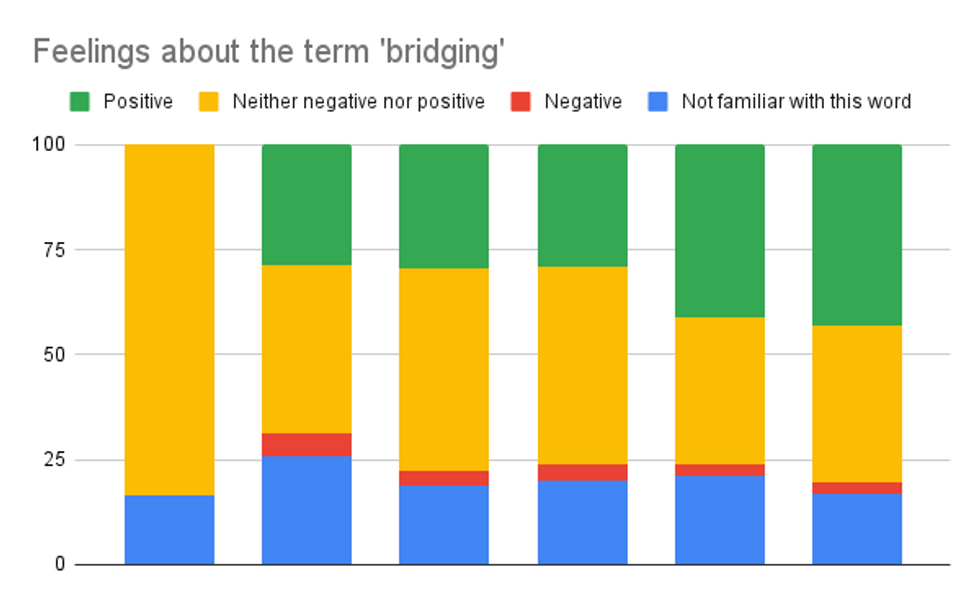

For example, “bridging” and “civic engagement” – concepts championed by dozens and dozens of organizations – do not resonate among many Americans. More than half of respondents, across partisan affiliations, said they feeling neither positively or negatively about the word “bridging,” or said they are not familiar with it.

Source: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement

Source: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement

“I also don't love the bridge metaphor,” said Pierce. “Think about a bridge — it's still two separate places (right and left) and then there's the work of building a stable structure that goes from one place to the other and then someone has to cross the bridge. I don't think you're ever going to see traction on concepts like bipartisanship until we don't have such an entrenched two-party political system, which is hard to imagine given the amount of money currently controlling US politics, especially since the decision in the Citizens United case. Right now partisanship is very profitable for politicians and corporations. As long as it's profitable it's going to be proliferated.

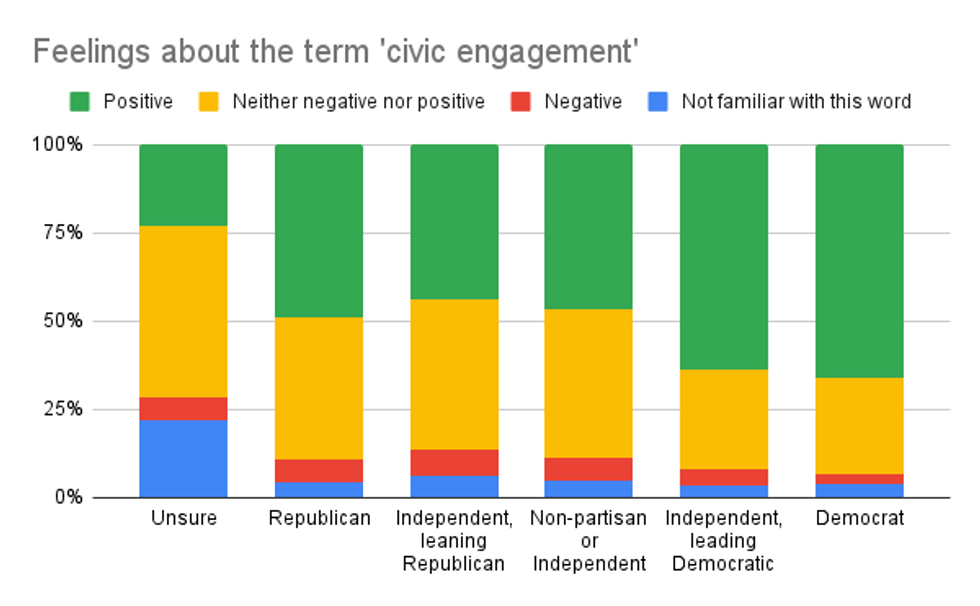

While Americans are more positive about “civic engagement,” particularly on the left, there’s still a significant share of people who say they are unfamiliar with the term.

Source: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement

Source: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement

Kristin Hansen, executive director of the Civic Health Project, is among those who see opportunities with such terms.

“Enough people across enough different sectors think these terms are working and will resonate with people,” said Hansen, who is deeply involved in bridge-building efforts. However, she does think there is an opportunity for some rebranding.

“When you use terms like ‘bridging divides’ and ‘bridging differences,’ you hear ‘divides’ and differences,” she said, explaining that the movement needs to start using more positive concepts. ”Building toward trust is more positive. Trust is the simplest word that conveys the same ideals and has broad resonance from right to left party because it doesn't sound so high-falutin.”

Among the other words Hansen is trying to bring to the bridging movement are connection, belonging and inclusion.

“We are evolving DEI toward something more like inclusion or belonging rather than identity markers,” she said.

Schildkraut also sees value in finding different language for bringing people together.

“One phrase you hear a lot in movement circles is ‘meeting people where they are.’ So yes, I can see why finding terms that resonate with people may be a better strategy than trying to get them to appreciate words like bridging and civic engagement in the way that scholars or organizers might use and understand those terms,” she said.