Anderson edited "Leveraging: A Political, Economic and Societal Framework" (Springer, 2014), has taught at five universities and ran for the Democratic nomination for a Maryland congressional seat in 2016.

Representative democracies by their very nature are bursting with conflicts over what policies should be adopted, at the local, state and federal levels. Autocracies, though they may have conflicts of beliefs and values amongst politicians and citizens, by definition are not bursting with them.

Even though politicians and citizens may disagree with each other and with the chief autocrat in the state, they must keep their disagreements to themselves. Otherwise, any display of disagreement would be regarded by the autocrat as a sign of disloyalty, which can lead to punishments ranging from ejection from office to death.

Not all forms of disagreement are permitted in a representative democracy. For one, you cannot express your disagreement with a fellow politician or fellow citizen by injuring or killing them with a gun or a knife.

When does the expression of nonviolent disagreements rise to a level where they are ethically, though not legally, unjustified? Indeed, at what point does the practice of politics reflect a disintegration of the body politic itself?

It is hard to nail down an answer to this question. Different countries have different customs, traditions and styles of their own, and thus what may cross the line for the French may not for the English or the Americans or the Japanese or the South Koreans.

In the American case, many commentators have warned that our democracy has been threatened in recent years by actions of former President Donald Trump and many Republican politicians, especially concerning the electoral process itself. While Democrats are not regularly charged with threatening our constitutional order, they have been charged by many commentators, including Jonathan Rauch, with sharing the responsibility the last 20 years for the dysfunction in Washington.

The future of American democracy is about as sure a thing as the future of the planet in light of global warming. Few scientists would say that life on Earth is definitely guaranteed for at least another 500 or even 100 years. Of American democracy there are those who believe our institutions, especially our system of elections, may in fact be scorched to the earth in 2024, and possibly 2022.

One can approach the fragile situation of American democracy's future from the left, the right or the center. When you approach it from the left, then the Republicans are the villains; when you approach it from the right, the Democrats are the villains. When you approach it from the center — as organizations ranging from No Labels to Braver Angels to the Bridge Alliance (which owns The Fulcrum) do — neither party is solely responsible for the damage that has already been done to our democracy.

Once you are in the center, however, there are many ways to plant your feet and make your case.

You can stand between the two parties — literally in the U.S. Capitol itself— and call on both parties to solve problems, indeed to be problem solvers. That is the approach taken by No Labels, which created the congressional Problem-Solvers Caucus.

You can also stand outside of Washington, D.C., and focus more on mobilizing American citizens, and organizations, to articulate an agenda for America. Frequently those outside of Washington who challenge the "establishment" come from one of the extremes on the ideological spectrum, left or right.

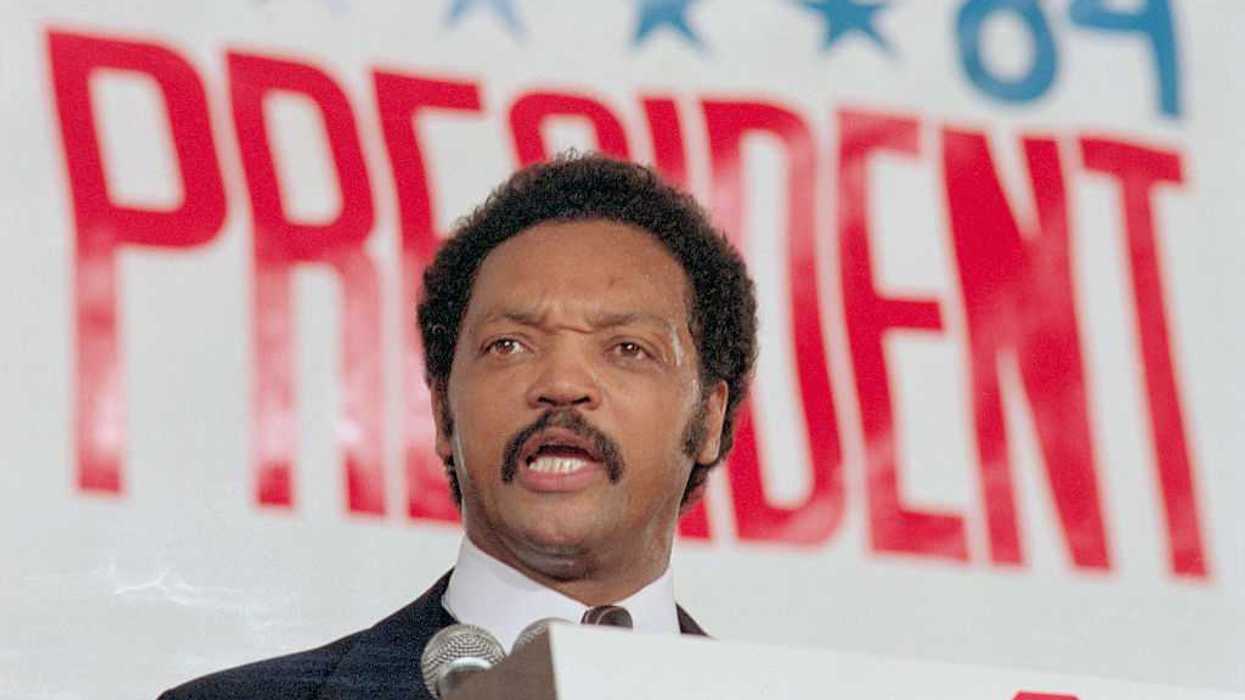

There is also a tradition of radical centrists, especially in the 1980s and 1990s — including Ted Halstead, Michael Lind, Tom Friedman (in an earlier life), Jesse Ventura, Matthew Miller, Mark Satin and John Avlon. They are animated by the idea of transcending the existing left and right of American politics to find a "new center," one that may even take extremist ideas or values from both sides.

A major problem with radical centrism is that it scares people because it is called "radical." Radical centrists intentionally mean to not be radical left wingers by saying they are centrists, but the name has always been a turn off.

Americans don't cotton to things radical.

“Third Way” Democrats, starting with President Bill Clinton, were themselves very influential in the 1980s and 1990s, but they were (and are) always moderate centrists and not ambitious centrists. Progressives on Capitol Hill today regard Clinton centrism as the source of the chief ills of the Democratic Party.

So if you are not going to be a radical centrist or a moderate centrist, then what kind of centrist should you be?

The starting point is to put aside the ideological spectrum. Maybe even work above it.

An ambitious synthesis of left and right or transcendence of left and right departs from the left-center-right spectrum while lifting ideas and values from it. Moderate centrists, in contrast, stay on the spectrum and find a compromise between liberals and conservatives without introducing fundamentally new language, concepts or frameworks.

Here is a policy proposal to start explaining this vibrant center perspective above the political spectrum.

A national family policy that offers a choice between child care support or a tax credit for stay-at-home parents after an initial paid parental leave policy is a policy that fits the mold. Progressive Democrats are single-minded about promoting equal opportunity for working women to return to work after paid leave expires, but new centrists seek to provide new mothers (or new fathers) with the option of staying home for at least two more years.

Moreover, the vibrant centrist is engaged in an activity to not only find a new center but to craft synthesis policies and mobilize people to join this creative effort.

The vibrant centrist, however, cannot be defined by a set of policies when their raison d'être is to actively work with others to craft a new framework for politics and articulate new public policies. In the same way that the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein famously maintained that philosophy was not a doctrine but an activity, ambitious centrism is not a doctrine but an activity.

Policies must ultimately be articulated, but they are not the heart of the new centrism. Activity is.

Saving American democracy starts with a fierce individual and organizational activity fighting for values and ideas not on the ideological spectrum but above it. This point of view can mobilize politicians in office and motivate people to run for office who do not take the party line.

This vigorous activity is not one of revolution and it could engage both parties. The process is still within the parameters of a reform. Like the Protestant Reformation, a vibrant centrist reform effort can build an alternative approach over a period of years. Many existing pro-democracy and bipartisan organizations that are currently fighting for reform could occupy this space together.

What is needed now is leadership.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift