Dayton is a former House GOP aide and a policy advocate at Protect Democracy, a nonprofit that works "to prevent our democracy from declining into a more authoritarian form of government."Marcum is a governance fellow at the R Street Institute, a pro-free-market public policy research organization.

It is rare these days that people have happy news to share in the nation's capital. But we are here to do just that.

Last week, the House Rules Committee held an extraordinary hearing on ways Congress could reassert authorities it has long ceded to the executive branch. It was extraordinary for its form, its substance and its energy. (And yes, we're still talking about a Rules Committee hearing.)

First, the form. The hearing used principles that were first developed by the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress. Established just last year, part of the purpose of this rarely discussed Modernization Committee is to "help Congress help itself" with new processes that make it more effective and less polarized.

Last week, the Rules Committee practiced what the Modernization Committee has recently preached. And the result was a hearing conceived on a bipartisan basis, with witnesses picked jointly by committee staff from both parties, and with unlimited time for committee members to probe witnesses and dive more deeply into substantive and complex policy questions.

Beyond these bipartisan successes, perhaps the most important symbolic moment of the hearing was this: Instead of turning over the gavel to another member of his majority, as is almost always done, when Democratic Chairman Jim McGovern of Massachusetts had to leave the room he handed it to the panel's top Republican, Tom Cole of Oklahoma.

To understand the importance of this small but significant gesture, it's important to understand that the Rules Committee's members are appointed by the Speaker with an eye toward making sure the majority always wins. Almost all controversial legislation passes through Rules, which sets the procedures for debating and amending bills on the House floor. The Rules majority has the most lopsided majority of any committee, essentially guaranteeing the Speaker will get the ground rules she asks for.

This means most committee proceedings are entirely party-line affairs. But, last week, as Cole noted in his opening statement, the committee did not function in "usual partisan camps of 9-4" but instead came out 13-0 in favor of improving the institution of Congress.

And this leads to the substance of the hearing, focused on how Congress can reassert national security authorities it has long lost or delegated to the executive branch. In a joint statement announcing the hearing, McGovern and Cole argued that Congress for many years has been abdicating its authority to presidents over such fundamental matters as going to war, monitoring the regulatory process and controlling federal resources and powers during national emergencies. This "has happened regardless of which party controlled Congress or sat in the Oval Office," they noted, and so bipartisan diligence on Capitol Hill will be the only way to recalibrate the balance of power toward the legislative branch.

In his opening, Cole furthered this sentiment, noting that the Founders positioned Congress in Article I of the Constitution for a reason: "It was no accident that they first described the powers entrusted to Congress on behalf of the American people. Indeed, the legislative branch established in Article I remains the most closely connected to the views of our nation's citizens to this day."

The witnesses, who fell across the ideological spectrum, agreed. Testimony from professors Laura Belmonte and Matthew Spalding's provided a historical background of an ever-expanding executive branch coinciding with a legislature that has become more reluctant to use it foreign affairs powers. Professors Saikrishna Prakash and Deborah Pearlstein offered a number of possible reforms.

The hearing's bipartisan goodwill and institutional focus were only surpassed by the committee's genuine energy for reform. In addition to McGovern and Cole, most of the committee attended the entire hearing. This is a rarity in Congress, let alone for a hearing that went on for nearly four hours.

Members had also clearly done their homework. Two members of both the Modernization and Rules committees, Democrat Mary Scanlon of Pennsylvania and Republican Rob Woodall of Georgia, asked detailed questions about Congress' structural role. Republican Debbie Lesko of Arizona emphasized deep thinking about these issues happening across the political spectrum and referred to a recent Republican Study Committee report that included many recommendations about taking back power it has long abdicated. Democrat Donna Shalala of Florida, who was Health and Human Services secretary in the Clinton administration, explained that executive branch officials often "celebrate" this abdication and try to "drive a car through" broadly (or badly) drafted legislation.

Optimism for congressional reform, however, is always marred by subsequent inaction. Members of the Rules Committee have taken the important first step of setting the model for other members and committees. From here, it is up to the public — and the people's branch of government — to continue this important discussion.

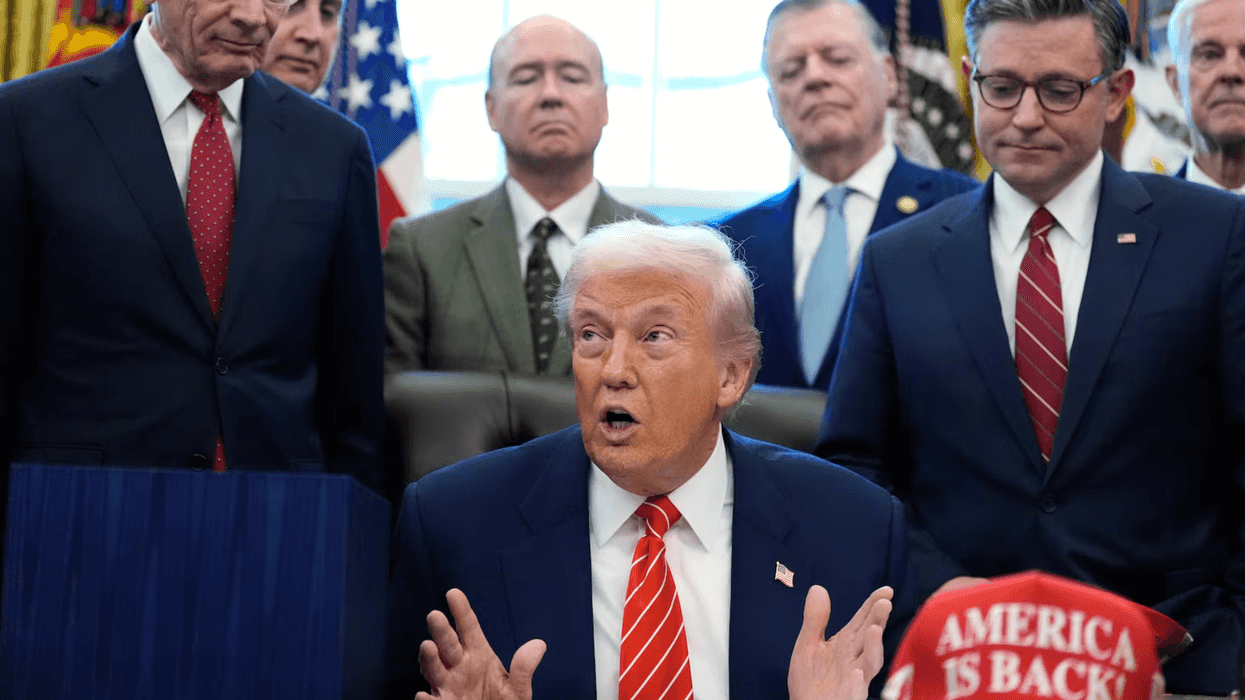

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift