Drutman is a senior fellow at New America and author of "Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America."

Well, here are some of my takeaways from Election Day, and some other thoughts.

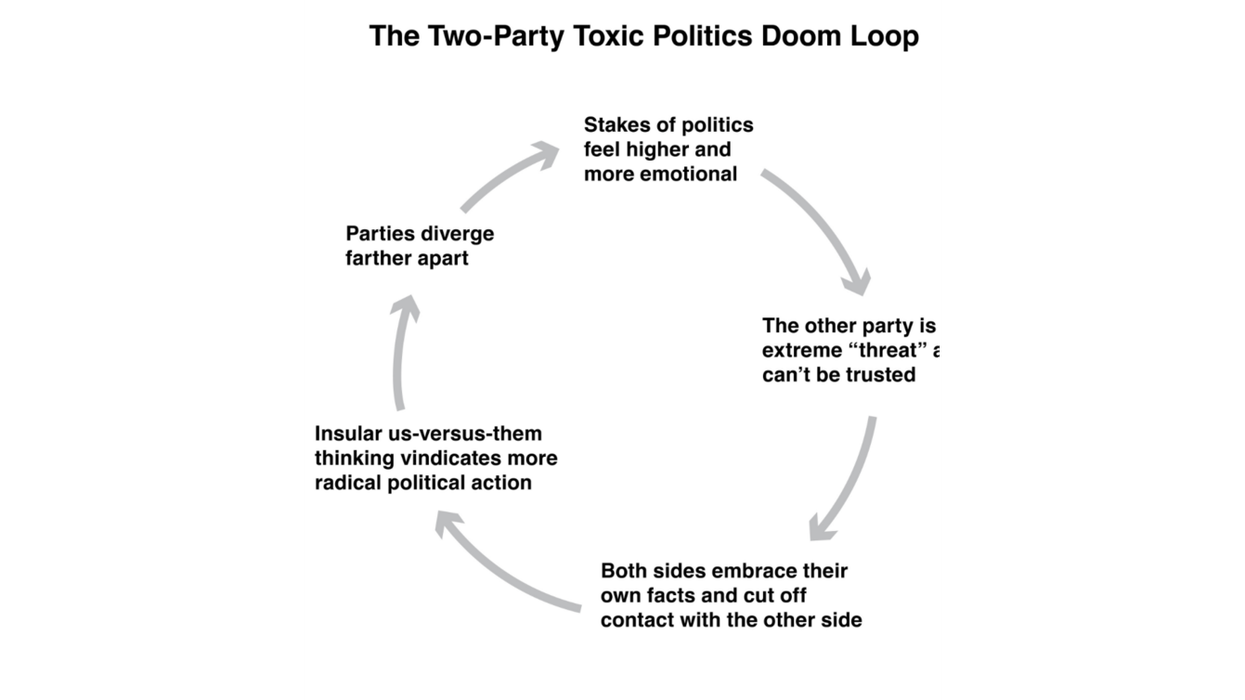

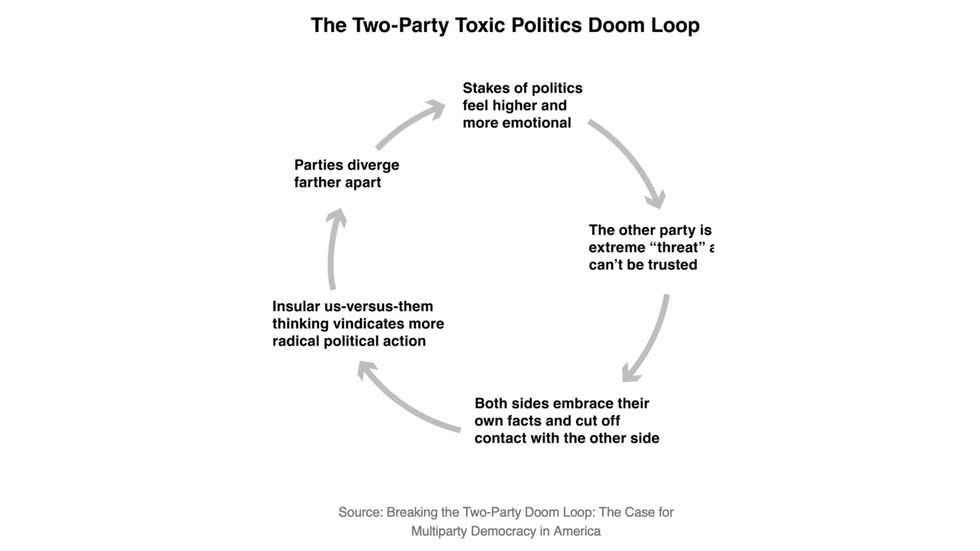

1. The two-party doom loop keeps getting doomier and loopier.

This was an ugly campaign. The tone was very nasty. The threats and dehumanizations grew quite dark. This is the two-party doom loop in depressing motion: a vicious cycle of escalating rhetoric around continually high-stakes, narrowly decided elections. As parties become more polarized, they compromise less and demonize more. It only gets worse and worse.

This self-reinforcing logic cuts at the foundational core of the democratic bargain — mutual toleration and forbearance. I only see it getting worse under a second Trump administration, which promises to be even more combative and vindictive.

Authoritarian leaders benefit from polarizing conflict. The ruthless us-versus-them dynamic gives them power to fight “the enemy within.”

The conflict is only going to grow more intense. Doomier and loopier, I often find myself thinking. This election did not reveal any off-ramps.

This makes me sick. It is like being on the scariest roller coaster ever and not being able to get off.

2. The anti-system vibes remain strong — and bad for incumbents.

Americans are in a sour mood and have been for a while. Overwhelming majorities report feeling dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country. For the last few years, the share of Americans feeling satisfied has hovered around 20 percent.

Such persistent dissatisfaction does not help incumbents. As I wrote earlier this year, no national political figure is viewed favorably. Incumbency, once an advantage in politics, is now a liability. Every election is now a “change” election.

This rumbling anti-incumbent dissatisfaction appears to be a global phenomenon, across democracies. We are in a kind of era of discontent. But this discontent seems especially pronounced in the United States. More than two-thirds of Americans think “the system” needs to change.

Harris at times tried to pitch her campaign as a “fresh start.” But ultimately she fell back on a campaign of continuity and defending the (distrusted) institutions. As the sitting vice president, she really had no other choice.

The big problem is that when voters are unhappy with the status quo, they only have one other choice. If that choice happens to be an authoritarian, then voters who just want “change” may wind up with fascism.

3. Complicated, incremental electoral reform is not a winning path out of the doom loop.

In six states plus the District of Columbia, voters had the option to open up their party primaries, adopt ranked choice voting or both, via ballot initiative. In one state, Alaska, voters were asked whether to preserve their reform.

Only Washington, D.C., voted in favor of open primaries and ranked-choice voting.

As an electoral reform nerd, this round-the-board rejection of primary and RCV reform was the biggest shock of the night. I had expected reform to pass in at least Oregon and Colorado, and possibly Nevada.

So what happened? Let me break it down.

In four states, the open primaries and rankedc hoice voting initiatives were yoked together into one initiative.

In Colorado, voters rejected Proposition 131, which would have moved the state to a top-four “all candidate” primary and a ranked choice voting election. (The vote was 55 percent no to 45 percent yes.)

In Nevada, voters rejected the same proposition (but with a top-five primary), by a similar margin (54 percent to 46 percent).

In Idaho, voters rejected their version of the measure even more overwhelmingly — 69 percent against, 31 percent in favor.

In Alaska, voters were deciding whether to keep their top-four-plus-ranked-choice-voting system, which they had approved narrowly in 2020 (when it was paired with a provision to eliminate dark money). The Alaska repeal effort appears to have narrowly succeeded, thus ending Alaska’s short-lived experiment with open primaries and RCV.

Only in my super-liberal home city of D.C. did an RCV and semi-open primaries initiative pass.

In other states, ranked choice voting and open primaries were on the ballot separately.

In Oregon, v oters rejected a standalone ranked choice voting proposition (60 percent against, 40 precinct in favor). In Arizona, voters rejected Proposition 140, to create a single, all-candidate open primary by a similar margin (59 percent no to 41 percent yes).

In Montana, voters considered two separate initiatives: CI-126, to create a single open primary, like Arizona, and CI-127, to require a majority winner. Voters decisively opposed CI-127, but as of this writing, they have only narrowly opposed CI-126, which remains too close to call.

Finally, South Dakota decisively rejected a top-two primary reform (modeled on California and Washington), 68 percent against to 32 percent in support.

Frankly, I think voters made the right choices in all these places, even if they didn’t always do it for the right reasons.

To me, the open-primaries-plus-RCV combo (often billed as “fiinal four voting” or “final five voting”) only further weakens parties (by pushing parties further out of the business of nomination). My view has long been that we need to build healthier and stronger parties. And that starts with giving parties more control over their nominating process, rather than allowing any schmuck to claim the legitimating label. These reforms would have moved us further in the wrong direction.

This combination also adds confusion and complexity to elections (making life difficult for already over-taxed election administrators). And making elections “nonpartisan” increases campaign costs and makes money even more important. This benefits wealthy candidates and donors even more than the existing system. The United States already has the most “open” primaries of any democracy in the world. Only in the United States can you register (for free!) as a member of a party and get to choose that party’s nominee.

I think there is a better direction for reform: combining fusion voting for single-winner elections with party-list proportional representation for multi-winner elections. This straightforward solution addresses the core problems voters care about: lack of choices, gerrymandering, lack of competition, etc., with a single transformative sweep.

And yes, I understood the case many made behind the smaller changes: Get some wins, build momentum, get people comfortable with the idea of electoral reform.

Given these overwhelming losses, it’s time to reconsider that strategy and explore new options and approaches.

This will be the subject of Part 2 tomorrow.

This article was first published in Undercurrent Events.