Problematic elections have become unsettlingly common this spring, but Georgia's primary is standing out as particularly disastrous.

By the morning after, civil rights and good government groups were joining mostly Democratic lawmakers in a stark warning: Without more spending, more polling places, more poll workers, more equipment testing and more efficiencies in their vote-by-mail systems, states across the country are bound to replicate Georgia's debilitating chaos.

And that, they said, would turn the November presidential into a national crisis, with the results in dispute and millions of voters concluding they'd been disenfranchised.

The situation would not be helped by a spread of the sort of angry partisan finger-pointing occurring in Georgia about why Tuesday amounted to a master class in how elections should not be conducted — especially in a battleground state that could face potentially record turnout.

After the state urged people to vote by mail, many absentee ballots arrived late, were for the wrong voter or never showed up at all. That forced thousands to risk Covid-19 exposure to head out to vote in person — assuming they could locate one of a shrunken roster of voting centers instead of their usual polling places.

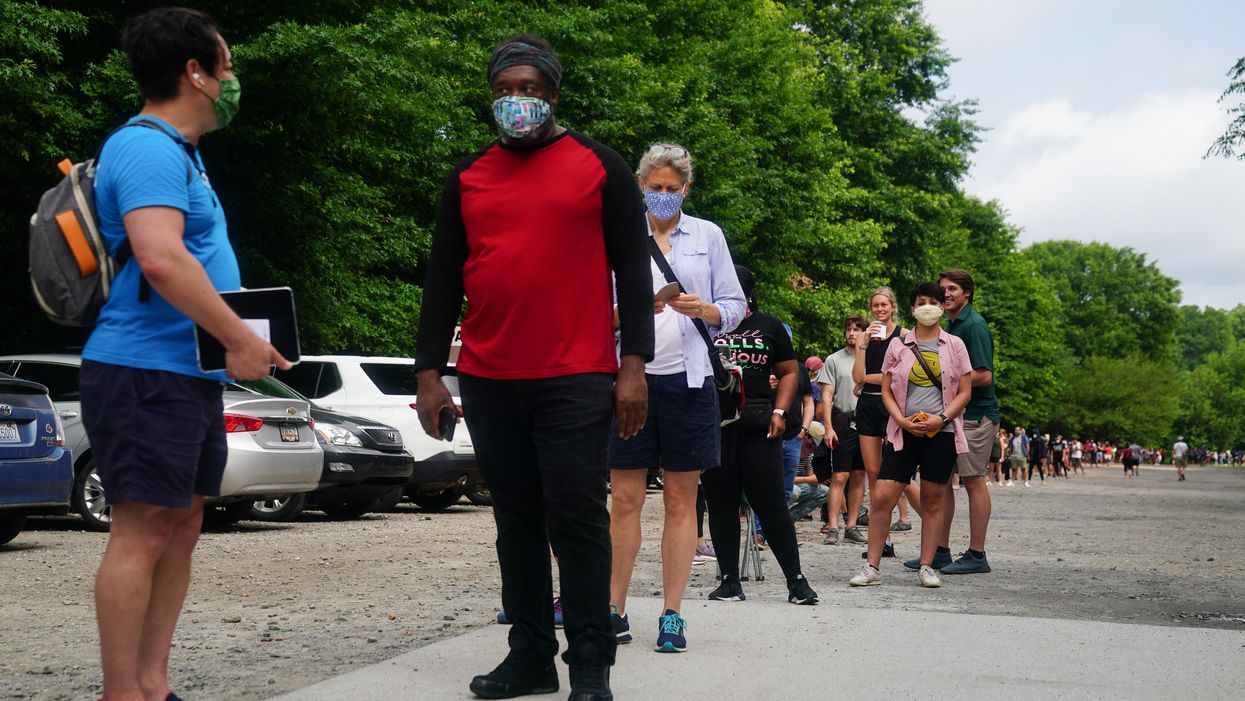

Once they'd arrived, many stood in line for several hours. (The last ballot in Atlanta was cast 195 minutes after the scheduled poll-closing time.) The roster of election workers was down; poll workers pressed into service only recently were minimally trained and overwhelmed. New touch-screen machinery malfunctioned frequently. And many precincts didn't have sufficient copies of paper provisional ballots as backup.

It was a perfect storm, which civil rights groups labeled a form of voter suppression that was as predictable as it was preventable.

"Georgia has had problems with voting for decades, but this was beyond anything in recent history that voters have seen," said Julie Houk of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which runs a hotline to help voters navigate election issues.

The problems, especially the long waits, were disproportionately worse in Atlanta and the closest suburbs, home to most of the state's black population. (A report from the Brennan Center for Justice, a progressive voting rights group, has concluded that black voters across the country waited 45 percent longer to cast their ballots in the 2018 midterm election than white voters.)

Voting rights groups say the state's Republican government could have done more to prevent these issues. For instance, officials knew well in advance about the problems with the new equipment — purchased for every polling station in the state in the past year, at a cost of $104 million, to enhance election security by replacing the electronic machines that had no paper backup. A pilot run of the machines last fall showed malfunctions, but the state decided to use them anyway.

Another issue was with the absentee ballot process. When the primary was delayed from March because of the coronavirus outbreak, the state sent all 6.9 million voters an application to vote by mail, but the vendor that produced the ballots was located thousands of miles away in Arizona. This distance caused delivery delays and other inconsistencies.

But Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger blamed county election officials, especially in Democratic areas, for the misbehaving voting machines and long lines. Even before the polls closed, he announced an investigation into how the voting was conducted in Fulton and DeKalb counties, which Atlanta stretches across, so problems could be fixed before November.

"Obviously, the first time a new voting system is used there is going to be a learning curve, and voting in a pandemic only increased these difficulties," he said. "But every other county faced these same issues and were significantly better prepared to respond so that voters had every opportunity to vote."

[See how election officials in Georgia — and every other state — are preparing for November.]

While this primary was particularly disastrous, voter suppression has been prevalent in Georgia elections for decades. And the state's strict voter ID laws, demands for bureaucratic exactitude and penchant for closing polling locations were all aggravated by the public health crisis.

Even basketball legend LeBron James spoke out about the primary. "Everyone talking about 'how do we fix this?' They say 'go out and vote?' What about asking if how we vote is also structurally racist?" he tweeted.

Democrat Joe Biden's presidential campaign called what happened "completely unacceptable." President Trump's campaign laid the fault at Georgia's decision to make mail voting easier, which the president asserts without evidence is a recipe for fraud.

For months, voting rights groups have pointed to inconsistencies in how states, including Georgia, are handling their elections. States could be better prepared if they had enough federal funding. In March, Congress allocated $400 million for states to conduct elections amid the coronavirus, but voting rights groups say this is not nearly enough.

Amy Klobuchar, the Minnesota Democrat who has been the major proponent of having the Senate join the House in providing as much as $1 billion more this summer, said she hoped the Georgia mess would spur that cause.

"When we don't properly fund our elections and develop plans to protect voters, Americans — often in communities of color — get disenfranchised and that's what happened," she said.

With proper funding, Georgia could open more polling locations, hire and train more election workers and process the larger share of mail ballots.

VoteSafe, a coalition of election administrators hoping to find bipartisan consensus for more money, emphasized the amount of work required in the next five months.

"From Wisconsin in April to Pennsylvania and D.C. last week to Georgia yesterday and certainly others, there are clearly opportunities to improve systems before November," said the new group's leaders, former GOP Gov. Tom Ridge of Pennsylvania and former Democratic Gov. Jennifer Granholm of Michigan. "Election administrators at the local, county, and state levels must act immediately and take seriously the threat of a second wave of Covid-19 to safeguard our elections this fall."