Eckam is a Texas software developer and graphic designer. Last year he self-published "Beyond Two Parties: Why America Needs a Multiparty System and How We Can Have It."

A year ago the Supreme Court declared partisan gerrymandering beyond the reach of its adjudication — while at the same time acknowledging the practice is "incompatible with democratic principles." So what can be done about it?

Many activists are pursuing independent redistricting commissions, which would certainly help. But something a little more radical would go further in safeguarding our democracy from partisan abuses of power.

Instead of electing each of the 435 members of the House to represent a district with a single member, we could create fewer congressional districts but then elect several members in each of them. For example: Texas, which because of population growth will probably be able to send 39 representatives to Congress for the next decade, could decide to have 13 districts with three members each.

These seats would be filled in a single election using a proportional, multi-winner voting method, such as the single transferable vote.

The number of representatives from a district is called its "district magnitude." Once the number reaches five or so, the electoral system becomes effectively immune to partisan gerrymandering, political scientist Douglas Amy of Mount Holyoke College has noted.

To see why, remember that single-member elections are winner-take-all. The stakes are very high for the parties because losing, even by a hair, means getting nothing. There's no proportionality of representation; one can only hope that disproportionality in one district is balanced by an opposite disproportionality somewhere else. The low fidelity of representation leaves a huge opening for political operators to skew their party's seat share, relative to vote share.

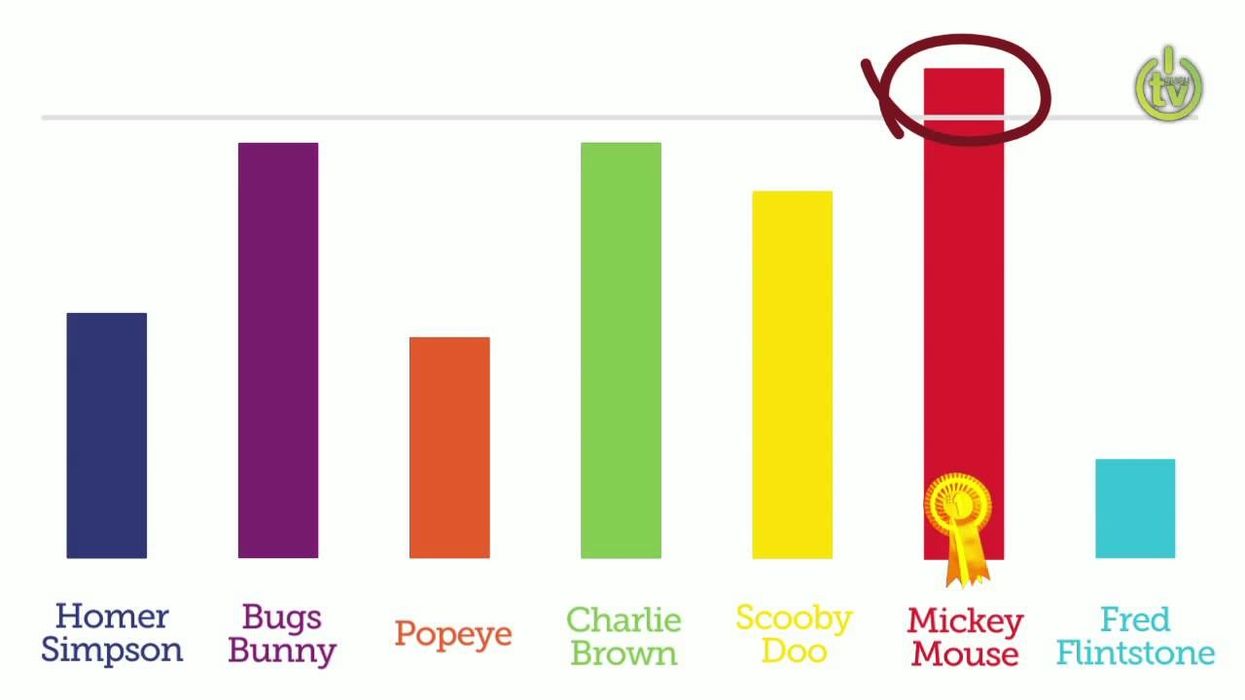

It's easy to see how this works by looking at the first illustration below. The big rectangular "state" has 60 voters, 36 Republican red and 24 Democratic blue, and they get to fill six single-member House seats. This can be done in some very different ways. In Map A, red gets 100 percent of the seats even though it has just 60 percent of the voters. But in Map B,the reds get just one-third of the seats despite its three-fifths of the voters — thanks to the power of the complementary redistricting tactics known as "cracking"and "packing."

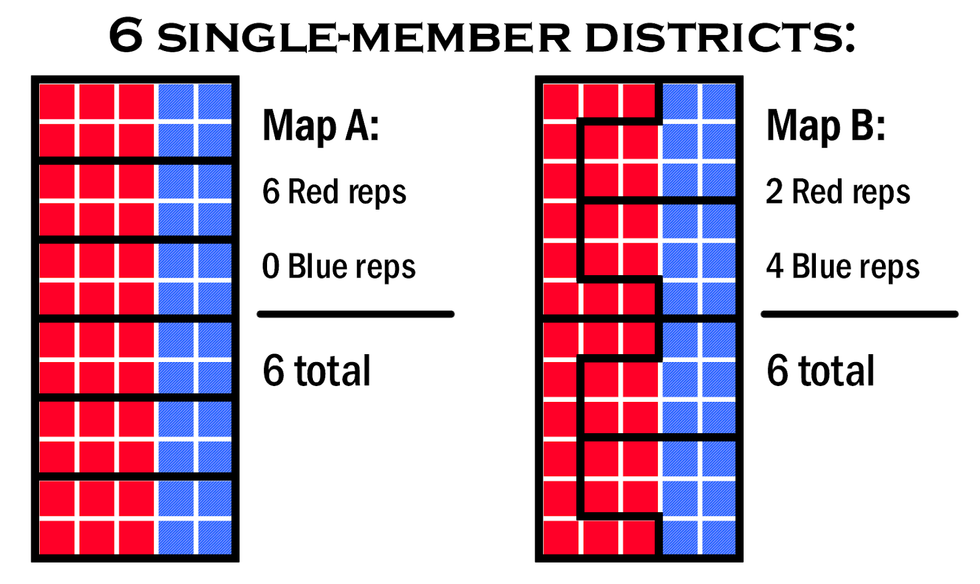

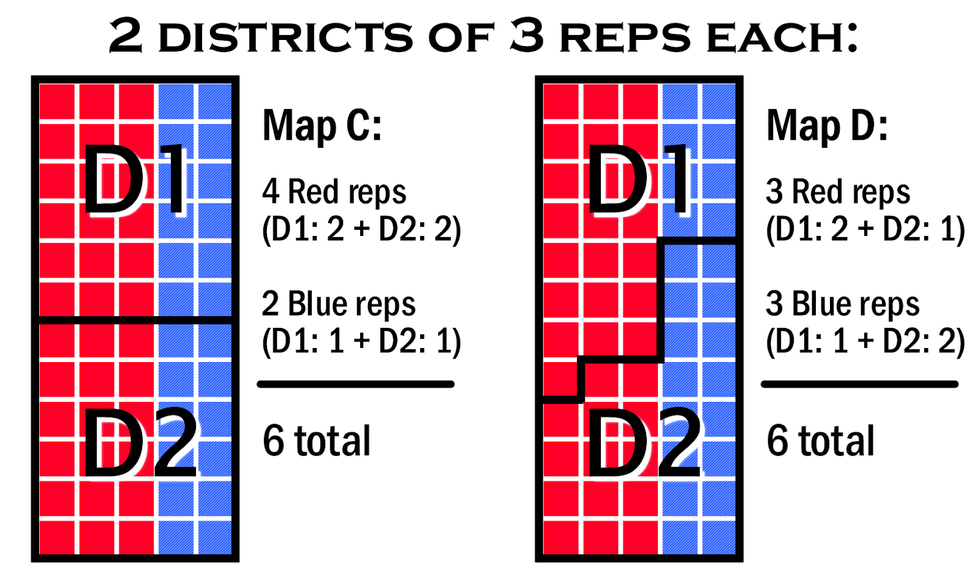

In this second set of schematics, below, the same jurisdiction elects three members each to represent just two districts.

Map C shows a simple division in which both districts have the same share of voters as the state, three-fifths red and two-fifths blue. But because of the multimember system the Democrats get to fill one of the three seats in each district, which isn't too far from their share of the vote.

Map D shows what might happen if the blue team drew the maps. By adjusting the lines so they have a slight majority in one district, while leaving enough of their allies in the other to maintain a single representative there, they manage to take half of the six seats.

That's still out of proportion to their share of the overall vote, but not too far out of line compared to what the blue team was able to achieve under the most aggressive single-member gerrymander scenario. What's more, there's no way to distort the balance any further than that. Blue cannot gain more representatives in one district without losing one in the other district.

Put another way, as district magnitude increases, the granularity of representation narrows further the scope for distortion. Greater representational accuracy renders attempts at gerrymandering unprofitable. It's ruled out structurally, rather than by a delicate balance of competing interests.

Multimember districts were used to draw the congressional maps of many states for much of American history. But it was usually for a wrong purpose — combined with non-proportional, "at large" election methods such as block voting in order to dilute the electoral strength of Black voters. In 1967, Congress prohibited multimember House seats, concluding that single-member districts were a good way to comply with the Supreme Court's landmark "one person, one vote" decision a few years before — and were an improvement over at-large elections.

That's no doubt true, but it's quite a low bar. Combining several-member seats with proportional representation is a far better way to ensure representation for minorities of all kinds — because it flows from the structure of the system. Under single-member districts, minority representation depends on groups being geographically concentrated, to some extent. Mapmakers can't draw a "majority-minority" district for a group that's perfectly integrated.

But why should integration and fair representation be in conflict with each other? With proportional multimember districts, they wouldn't be.

A bill stuck in Congress would require multimember districts in all states with more than one representative. Alternatively, Congress could simply repeal the 1967 law and let states decide. Local reform would also help, both to achieve better representation and to raise awareness.

Of course, it won't be easy to get legislators to act. It will require sustained effort, starting with a greater understanding of how the switch would mean fairer representation for all Americans. There's a lot of "bang for the buck" here — the costs may be somewhat higher than for independent commissions, but the benefits are also greater.

That gerrymandering is such a big issue in our democracy attests to deeper problems of representation. Only because of the partisan duopoly are the politicians (either Republicans or Democrats are always in control) able to abuse their power to suppress competition. Why not attack this problem at the root? Given time to become established, proportional multimember districts would loosen the grip of partisan interests over our democracy by depriving them of majority power.

James Madison wrote that since it's impossible to eliminate factions, we need to find ways to control their pernicious effects. His idea was that an extended republic would encompass a greater variety of interests, making it less likely that an oppressive majority could be established.

Gerrymandering is clearly one of many such pernicious effects of faction. Multimember districts would not only end the political profitability of such mapmaking but also begin to address the deeper issues of representation that now enable the practice.