Kevin Frazier will join the Crump College of Law at St. Thomas University as an Assistant Professor starting this Fall. He currently is a clerk on the Montana Supreme Court.

Disastrous. There's no other word to describe the state of civic education in the U.S. In the wake of the latest test results released by the National Assessment of Educational Progress it would be hard for anyone to conclude otherwise.

According to the NAEP, just one in three eighth grade students--individuals on the cusp of voting--can describe the structure or function of government. On the whole, barely more than one out of every ten students scored at or above the proficient level.

The worrying state of civic education should have been a crisis thirty years ago--when the first nationwide assessment was administered and students earned an average of a mere 259 points out of 500 (on the most recent test, students averaged 258). Though such a long spell of inadequate attention to civics may suggest that renewed attention to teaching the fundamentals of our democracy is too little, too late—to give up on civic education is to give up on our democratic experiment.

The good news is that the horrendous results have already caused an appropriate level of panic--headlines covering the dismal results demonstrate popular concern that we’re sowing the seeds of our own democratic demise by leaving the next generation the keys to a governing system they don’t understand. It’s as if we’ve left our kids a sports car and neglected to teach them how to drive a stick shift.

Assuming that this panic increases the educational resources paid to civics, the question is how to introduce students to a system that is undergoing a troubling bout of partisanship and gridlock.

Do we emphasize how our democracy should be (civic optimism), how our democracy is (civic cynicism), or how it was (civic memory). A recent experience with a group of elementary students suggests we need a mixture of all three, with an emphasis on civic optimism.

I provided a group of youngsters a tour of the Montana Supreme Court--where I work as a judicial clerk. The group peppered me with questions after I covered the basics of the court.

For the most part they asked questions pulled from the headlines: ”What happens when a judge doesn’t seem ethical?” “Do judges think about their friends when they make decisions?” “If a judge gets too old, how long can they keep their jobs?” In other words, they seemed to have received an informal civic education grounded in justifiable cynicism--justifiable because few would argue that how our system operates today aligns with how we’d expect it to run under ideal conditions.

Notably, they didn’t ask many questions about how our judicial branch and democracy as a whole have changed over time. They also didn’t inquire into when, if ever, the issues they heard discussed at the dinner table were less common or, at least, less severe. Absent having a civic memory--familiarity with the twists and turns of our democracy over time, the students appeared to think that this is how officials and voters have always behaved.

Most importantly, the students didn’t bring up any ideas for how to remedy the status quo and develop a more resilient and responsive democracy—the sort of questions that rely on an education in civic optimism.

So while we need to make sure that students understand how to drive our democracy, they must also have the skills and education necessary to decide where they’ll steer our grand political experiment.

Civic optimism is hard to teach, hard to test, and hard to measure, but if the next generation isn’t asking how we can improve our democracy from an early age, then we’ll likely be stuck in neutral.

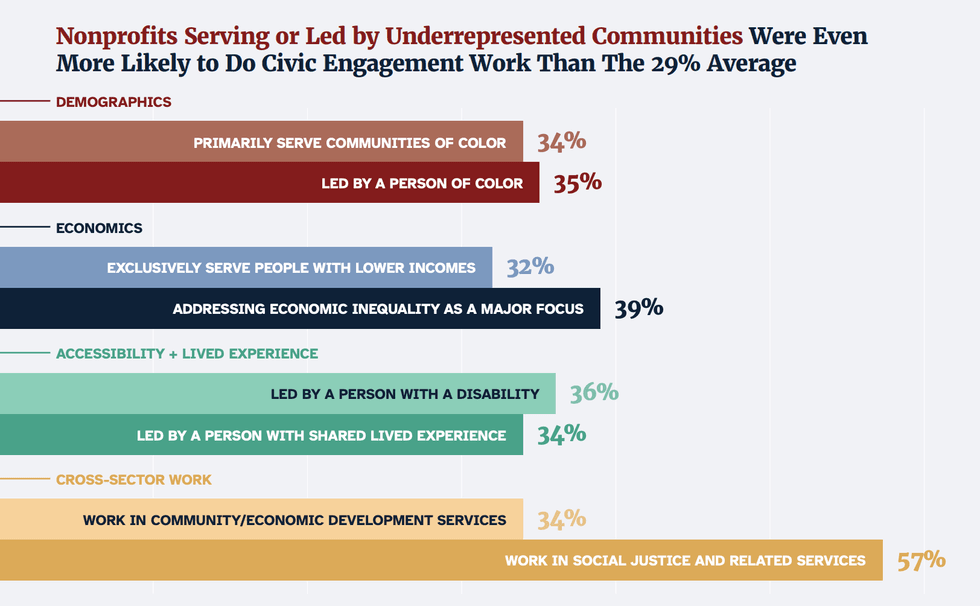

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift