WASHINGTON — For months, Reta Mays’ treachery slipped through the cracks at the VA hospital center in West Virginia, where she worked as a nursing assistant. By injecting insulin into elderly patients who didn’t need it, she murdered seven people from 2017 to 2018.

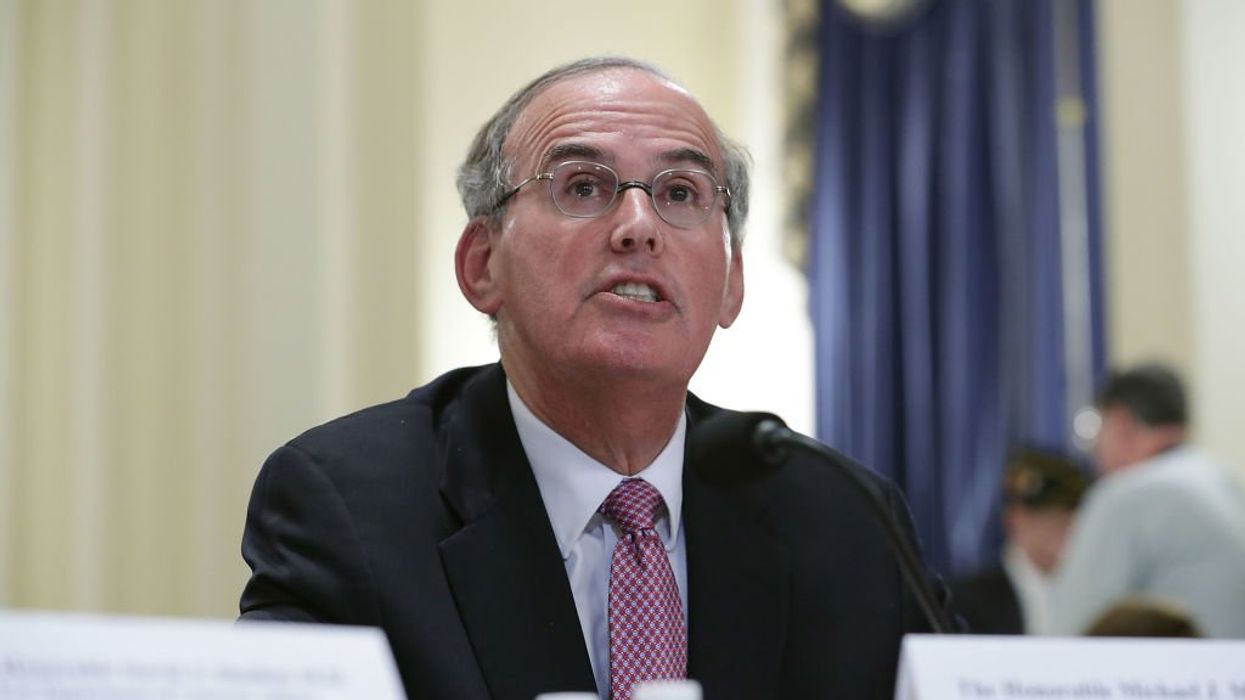

She eventually confessed, but in the meantime, the VA’s Office of Inspector General, led by Michael Missal, began investigating where things had gone wrong. Three years later, in 2021, Missal’s office released a damning report.

Before they hired her, the VA failed to check Mays’ background adequately. She lacked any official certificates or licenses as a caregiver and was accused of using excessive force against inmates in her previous job as a correctional officer

As he did throughout nine years as an inspector general, Missal’s report made the agency look bad by shining a light on its mistakes. Like the dozens of other inspector generals, known as federal watchdogs, Missal and his office are supposed to be independent so they can conduct thousands of vital reports and recommendations for their parent agencies.

President Donald Trump broke precedent in his first week back in office by firing 17 inspector generals, including Missal. Some are now suing to get their jobs back.

Last Wednesday, Missal and seven other former inspector generals filed a lawsuit against the president, claiming he had broken the law by failing to inform Congress 30 days before the removals and providing detailed explanations.

“The firing of the independent nonpartisan inspectors general was a clear violation of the law,” Missal said in an interview with USA Today. “The IGs are bringing this action for reinstatement so that they can go back to work fighting fraud, waste, and abuse on behalf of the American people.”

Many inspector generals had years of experience ferreting fraud and waste in federal agencies, including the Pentagon, the Departments of State, Education, Labor, and Agriculture.

Trump’s dismissal of the inspector generals, including some of his own appointees, soon sparked widespread criticism.

“Inspector General Missal has served his office with integrity and led a number of unbiased investigations during the Biden and first Trump administrations that Congress relied on to perform its oversight duties and improve the quality of care and benefits delivered to our nation’s veterans,” said Rep. Mark Takano (D-Calif.).

According to last week’s lawsuit, Missal’s access to the VA’s devices, networks, and buildings was quickly cut off.

Two days after the lawsuit was filed, a federal judge denied the inspector generals any chance of immediate reinstatement to their jobs, potentially lengthening the legal battle ahead. The judge then gave the Trump administration a week to respond to their requests.

Neither Missal nor his legal team responded to requests for comment before this story’s publication.

While the Trump administration never explicitly explained his firing, the Mays’ investigation was one of the many instances in which Missal uncovered scathing health scandals and exorbitant spending at the VA during his nine years in office.

Under his tenure at the VA, Missal charged the Trump administration's acting VA secretary with blocking access to data on whistleblower complaints. He also uncovered critical flaws in a $10 billion electronic health record system at a VA hospital in Spokane, Washington.

Missal was appointed in 2015 as the VA’s inspector general by former President Barack Obama and confirmed by the Senate. At the time, the job had been vacant for almost two years.

Missal’s acting predecessor, Richard Griffin, resigned following allegations that he interfered with federal investigations. A group of VA employees also revealed that Griffin’s office had attempted to retaliate against whistleblowers.

Missal’s appointment, as many hoped, turned the page.

“For far too long, the VA OIG’s lack of permanent leadership has compromised veteran care, fostered a culture of whistleblower retaliation within the agency, and compromised the independence of the VA’s chief watchdog,” Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.), who served then as the chairman of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, said at the time.

Before the VA, Missal had a long history working in law firms. He spent over 25 years as a partner at K&L Gates LLP in Washington, D.C., specializing in government enforcement and business protection services.

He also helped oversee multiple large-scale bankruptcy protection cases involving the New Century Financial Corporation and WorldCom.

Missal became one of the longest-serving VA inspector generals since the inspector general positions were first widely established in 1978 under the Jimmy Carter administration.

At the time, Carter suggested that inspector generals could be “perhaps the most important new tools in the fight against fraud.” He viewed the move as even more essential to restore public trust after the Watergate scandal involving President Richard Nixon,

Since Carter, Presidents Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama have made similar efforts to safeguard the presence of inspectors general within the government.

Jerry Wu covers national security and veteran's affairs in Washington D.C. for Medill on the Hill. The San Diego native is a sophomore at Northwestern University studying journalism and international studies.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room