I come from a long line of racists.

Tracing my ancestry back to the early nineteenth century, I discovered that my great-great-great-grandfather emigrated from Ireland and then drifted south, eventually settling in Dallas County, Alabama. Daniel Brislin called Selma home.

He was a cabinet maker, and a decent one at that. The Selma Times Journal reported that he was also exceptionally generous: “The respect and esteem in which he was held by the whole town, and especially the poor, whose staunch friend he was, was attested at his death.” A George Bailey-like figure, Brislin (our surname would morph over time into “Breslin”) was known to forgive payment on a table or a chest of drawers he crafted for a fellow Sel-towner. He regularly fashioned furniture on the commitment of a handshake, a promise, an IOU. That’s what you did in Alabama, I’m sure he would say. You trusted your neighbor.

Unless that neighbor had a different skin color.

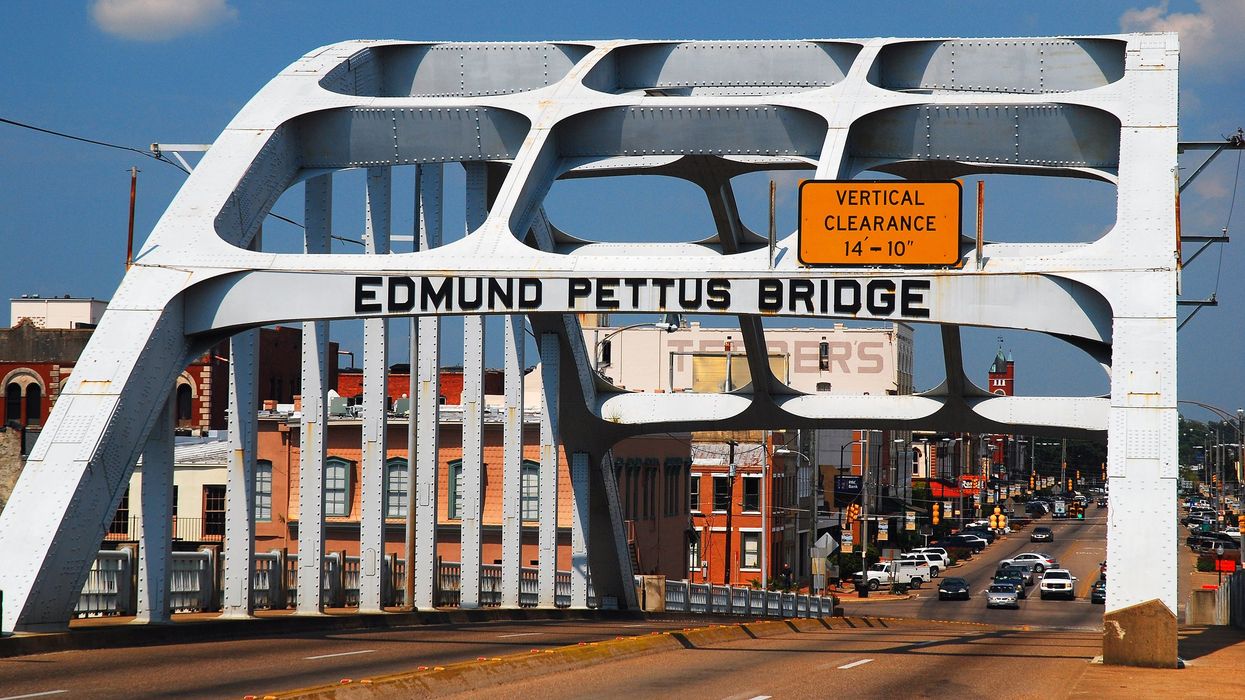

Now, there is no historical evidence that my great-great-great-grandfather was an enslaver. And there is no suggestion that he treated the growing Black population of Selma with conspicuous disdain. But he was friendly with Edmund Pettus, the infamous U.S. Senator and white supremacist who fought for the Confederacy and who wore the distinctive costume of the Grand Dragon, the state’s ranking Ku Klux Klan officer. They walked in the same circles; they worshipped in the same churches; their children went to the same schools. To be sure, the two enjoyed the privileges of whiteness in an antebellum Alabama. No one should doubt that my forebear shared much in common with the famous bridge’s namesake.

How do I make sense of this past, this blemish on my family name, this dent to my identity? Daniel Brislin bore me, after all. Not literally; there were many Brislins and Breslins between him and me. But it seems the prejudice of my earliest forefathers only diluted over time. It never fully disappeared.

To start, I realized I could not make much sense of anything in the comfortable confines of my home. Upstate New York has its demons, but it does not carry the heavy burden of American slavery. Or at least not outwardly.

So I recently accompanied my adult daughter on a journey to our ancestral homeland. She’s been to Alabama before—we’re enormous Crimson Tide football fans—but never exactly on a civil rights pilgrimage. Specifically, I wanted to explore Montgomery’s unique legacy in the nation’s enduring struggle for racial equality. I’ve been to Selma and I’ve walked the Edmund Pettus Bridge. I’ve stood in front of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. I’ve even traveled to Scottsboro. But I had never been to Montgomery. I felt I needed to go.

The city, of course, is the epicenter of the civil rights movement. The state’s house of government, Montgomery, was also the first capital of the Confederate States of America. It thus has profound symbolic importance. It was the final destination of the Voting Rights Marches organized by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, and others. It boasts more than its fair (or should I say “fare”) share of historical heroes—none grander than Rosa Parks, who famously refused to surrender her seat to a white man on a Montgomery city bus. Americans forget that Dr. King cut his pastorate teeth at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church across the street from the State Capitol and just around the corner from what was the first Confederate White House. It was in Dr. King’s place of worship that so much of the civil rights strategy was birthed.

Today, the Legacy Sites are the heart of Montgomery’s racial retelling. Three spaces in all, the Legacy Sites are intended to “invite visitors to reckon with [America’s] history of racial injustice in places where that history was lived.”

The Legacy Museum is a powerful and interactive object space that transports visitors from the slave ships—where more than 12 million Africans experienced the brutal conditions of the trans-Atlantic passage and more that 2 million died on the voyage (the mental image of a cemetery with several million souls buried at the bottom of the sea is hard to forget)—through Reconstruction, forced segregation, Jim Crow, and finally mass incarceration.

Freedom Monument and Legacy Park include a boat ride on the Alabama River, a major waterway supporting the slave trade.

Both are impressive. But it was at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice that my daughter and I began to understand the significance of our family’s legacy. The six-acre outdoor space is both commemoration and exhibition, deeply somber and penetratingly artistic. It tells the story of America’s racial terror lynchings. Over 4400 Black men and women were murdered because of their skin tone, tied to trees and posts and bridges, and left to hang limp and exposed. Each victim of these racial executions has their name inscribed on one of the corten steel blocks that, together, form an indelible sight. The memorial is beautiful and despairing in equal measure.

The exhibition is also allegorical. Visitors navigate the space by walking under blocks that are attached to rods by noose-like connectors, unsubtly suggesting that we are all spectators and participants in a real-life lynching. The blocks themselves resemble both coffins and the human form. The durability of the steel stands in contrast to the frailty of the deceased. The indifference of the executioner is powerfully vanquished by the permanence of the blocks themselves.

Lynchings were a display of racial power – THE most jarring and vicious show of racial control invented by man. The snapping of the neck or the suffocation that occurred were meant to convey dominion. Lifeless bodies were left for all to see. Nineteen of these gruesome demonstrations were staged in Dallas County during the Jim Crow era, the second-highest number in the entire state. Selma claims its share of them.

Deep down, I know that my great-great-great-grandfather must have been part of that terror. In a sense, then, that terror now courses through my veins. And my daughter’s. Aside from facing our past through education, dialogue, and raised awareness, I can’t shield us from the cruelty we inherited.

They say that silence is acquiescence. At best, Daniel Brislin stayed mum while Black persons in Selma and throughout the South were subjected to unimaginable cruelty, torn from their families, treated with scorn and reprisal, lynched for the most inconsequential “transgressions,” and taught that the white patriarchy considered them morally inferior. My condemnation of his silence is easy, trite, almost. And yet even in this vastly polarized moment, I think we can all agree that any form of racial dominion is wicked. It is now; it was then. I journey on.

Beau Breslin is the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair in Government at Skidmore College.

Why does the Trump family always get a pass?