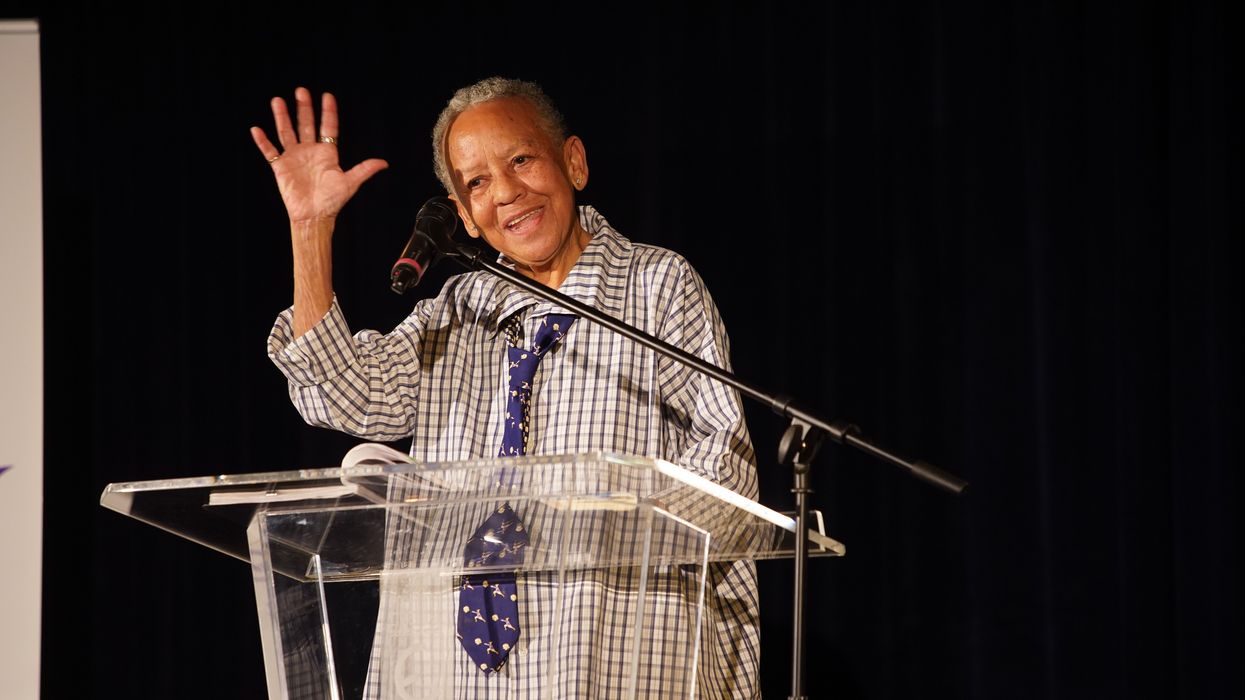

Earlier this month, we lost a voice that rang for decades with the clarity of truth and the warmth of eternal joy. Nikki Giovanni, the acclaimed poet, professor and icon of the Black Arts movement, passed away at the age of 81. The news struck me with the force of personal loss — not just because we lost a literary giant but because Giovanni's words have been a constant companion in my journey toward understanding the fullness of Black consciousness and the power of poetic expression.

As I sit with this loss, I remember how Giovanni's work exemplified what James Baldwin called "the artist's struggle for integrity." As a leading voice in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and '70s, her fiery and radically conscious poetry challenged social conventions while celebrating Black life's beauty and resilience. She didn't just write about revolution — she embodied it in every verse, her teaching and every dimension of her public life.

My first encounter with Giovanni's work was in the early years of high school. Her words didn't just speak to me; they ignited something profound within me. In “Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day,” she wrote of the sweetness that persists even in life's storms — a metaphor that would become central to my understanding of Black joy as a discipline of resistance. Her ability to weave together the personal and political, the tender and the fierce, showed me that our stories could be both protest and celebration. Her work became a source of inspiration, motivating me to search for my identity as a seminarian.

For 35 years at Virginia Tech, Giovanni shaped generations of writers and thinkers, proving that the classroom could be a space of radical imagination and transformation. She understood that teaching was about imparting knowledge and awakening consciousness. Her legacy lives on in the countless students who learned from her that poetry could be both a sword and a healing balm. While others might have been content to document our pain, she celebrated our triumphs, love and ordinary moments of grace. As a cornerstone in the Black Arts Movement, she demonstrated that our resistance could be expressed through celebration as much as through protest.

Giovanni's influence was more impactful than ever imagined in my development as a preacher-prophet. Her fearless truth-telling informed me that authenticity was not just about speaking truth to power but about speaking truth to ourselves. When she wrote “Nikki-Rosa”, she wasn't just telling her story — she was permitting all of us to tell ours, to claim our narratives as worthy and beautiful. She was signaling it was alright to insert one's self in the subject line. Giovanni's pen was never divorced from the struggle for justice. Her ideas about Black nationalism were integral to her poetry and activist work, yet she never let ideology overshadow humanity. She taught us that militancy could coexist with tenderness and that revolution could be fueled by love as much as anger.

Sister Nikki’s passing leaves a void in American letters that cannot be filled, but her influence ripples outward through generations of writers, activists, proclaimers and dreamers. Many who sat at her feet learned from her that our stories matter, that joy is a superpower and that love is revolutionary. She showed us that Black consciousness wasn't just about understanding our oppression — it was about recognizing our magnificence. I want to believe that Nikki Giovanni wouldn't want us to dwell in sorrow. She wants us to create, celebrate and continue liberation through love and language. Her words remain a beacon, showing us how to transform pain into power, find light in the darkness and make poetry out of the raw material of our lives.

In one of her final interviews, Giovanni reminded us that her dream "was not to publish or to even be a writer: My dream was to discover something no one else had thought of." She achieved that dream many times over, discovering new ways to articulate the Black experience, new paths to freedom through words and new ways to love ourselves and each other.

Farewell to our warrior-poet, teacher-activist and champion of Black exuberance. I pray we carry forward writing our truths, teaching our children, loving fiercely and resisting beautifully as she did. Nikki Giovanni showed us that poetry could be a path to liberation. Now, it's our turn to walk that path, to create our own verses in the ongoing story of freedom and human dignity.

Rest in power, Sister Giovanni. Your words will forever be our revolution.

Johnson is a United Methodist pastor, the author of "Holding Up Your Corner: Talking About Race in Your Community" and program director for the Bridge Alliance, which houses The Fulcrum.