Nevins is co-publisher of The Fulcrum and co-founder and board chairman of the Bridge Alliance Education Fund.

We need the space, time and safety to explore options for co-creating our future. We need to pilot ideas and practices that could strengthen our commitment to democracy. The two-year election cycle in the United States is currently designed to keep us in an endless loop focused on elections. What our nation needs is more imagination, creativity and experimentation. We need functional governance. And in this time of increasing political violence, how might we avoid or minimize harm with a future vision of inclusion and belonging – for all people? All. People.

To make this a reality, we need advocates for Justice, Equity, Dignity and Inclusion, or JEDIs for democracy.

In August of 2022, Bridge Alliance convened 30 JEDI fellows, containing a BIPOC majority as a representation of the future of our nation. These JEDI’s actively engaged around deepening relationships, sensemaking and solutions to sticking points in our current system; received leadership development and a foundation on which to draw from for the rest of their careers.

In this Part 1 of a series we focus on JEDIs in the news.

JEDI Jerren Chang is the founder and CEO of GenUnity, an organization designed to build a community based on our shared humanity.

Chang says at GenUnity “we envision a community by everyone for everyone, because when we are co-creators in building the systems that impact us, we are all better off. We bring residents together to tackle the issues critical to their communities, starting by connecting their own lived experiences to the systems and power structures that shape them. Together, residents translate their passion and learning into civic action — from introducing new legislation to changing workplace policy — ultimately transforming what we believe is possible with democracy.”

GenUnity’s issue-focused community leadership programs (like Health Equity in Boston) convene up to 50 residents — from ‘proximate experts’ experiencing the issue to the ‘siloed experts’ working in institutions to address them — for ten weeks, three hours per week. Through facilitated sessions and small-group discussions with local partners, members go through successive modules that build up their understanding of the issue, connecting people’s lived experiences to the systems and power structures that shape them. In the process, they develop leadership skills like active listening, systems thinking, and action planning. The inquiry-based conversations that members engage in help folks uncover “why” issues persist in their community and “how” they can use their power to drive change. Upon completing the program, members join the Lifetime Community of Practice (LCOP), where they continue to build deep peer-to-peer connections and collaborate on the execution of their action plans.

Since 2020, they have launched four programs on Health Equity and Housing Insecurity, serving nearly 150 residents. One of their residents, Gloribel (Housing ’20), met Suffolk Law School housing discrimination researchers and connected them with her representative, Adrian Madaro, and together they drafted and introduced legislation to combat bias against voucher holders and Black renters. Another resident, Alex (Health Equity ’22), learned how changing reimbursement policies could expand access to affordable LGBTQIA+ and behavioral healthcare, especially in communities of color, and is now spearheading this effort within Blue Cross MA.

Chang and his team believes in and are committed to being champions for equal opportunity, individual agency, and the transformational power of compassion and community to build a better world.

These guiding beliefs start with his parents. On his father’s side, his grandfather benefitted from a civil service exam that provided a pathway to education and a career. This in turn allowed him to move his family from poverty to the middle class, even while escaping to Taiwan during the Chinese Civil War. His mother was born an orphan in Malaysia and adopted by a low-income single mother whose individual compassion changed the course of his mother’s life. Through their journeys, Chang experienced his generational inheritance in America as an opportunity and obligation to tap into our compassion for each other — to build systems that provide equal opportunity and, by extension, the agency and liberation that all deserve.

In reflecting on his upbringing Chang says:

“G rowing up as a scrawny Asian-American kid in upstate New York, I didn’t know what embracing this generational inheritance looked like. I got lucky. I I found opportunities for civic learning through work, from researching global migration at McKinsey, to doing policy work at the Chicago Mayor’s Office, to graduate school at Harvard’s Kennedy and Business Schools. Most importantly, these experiences enabled me to see how our top-down, technocratic approaches to social change conflate compassion with control, agency with paternalism. Without transforming the underlying power dynamics of who gets an equal say in systemic decisions, we will never build the systems of opportunity our communities deserve. At GenUnity, I am committed to a different kind of leadership — one that centers equity, not ego; decentralizes power to those most proximate to community needs; and builds a culture, organization, and model that mirror our hopes for our democracy: compassionate, humble, diverse, and equitable.”

GenUnity’s work is shifting our narrow conceptions about civics (e.g., voting and volunteering) to an empowering understanding of ‘civic well-being.’ Civic well-being recasts civics as a set of universally relatable questions: How are people in my community doing today? How do our systems and power structures shape those outcomes? The use of well-being concretizes why civics matters to each of us as individuals, organizations, and communities. It provides a framework to understand the strengths we bring — such as the unhoused person who knows how to navigate existing social services — and where we need support — such as connecting with decision-makers with whom we might not have access. At a time when it feels like the country can’t agree on our underlying beliefs, civic well-being offers us a pathway to claim our agency, recognize that not all civic engagement is equally helpful, and engage in productive practices to promote our own and our communities’ wellbeing.

Chang believes we can transform civic culture to one where people most impacted by issues are seen as experts, centered and empowered to co-create solutions alongside institutions; where these relationships are not just transactional to design policies and practices, but consistent and longstanding pillars of solidarity; where our community is truly by everyone, for everyone.

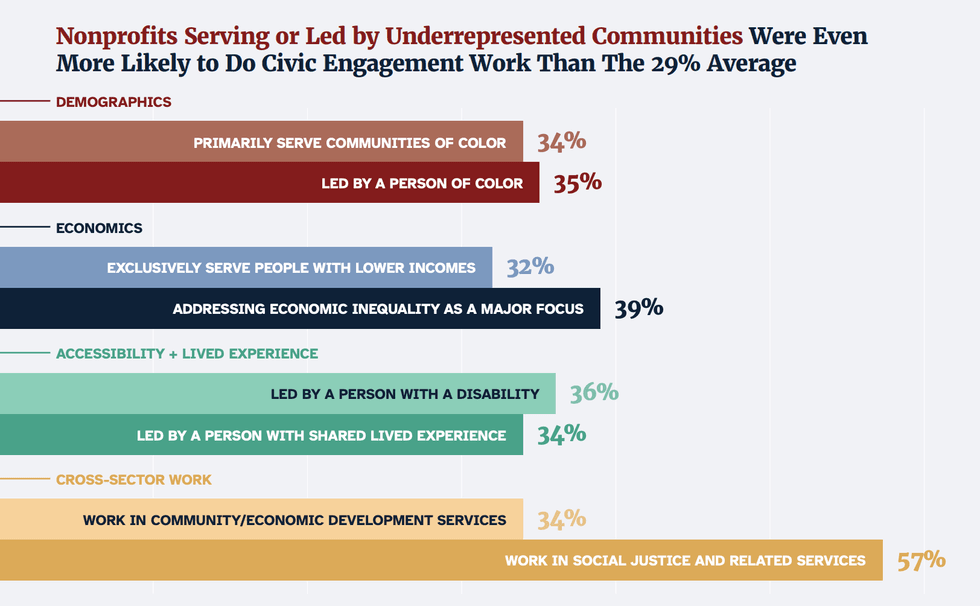

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift