In one of the most narrowly divided Congresses in recent history, as party loyalty and the filibuster are often key determinants of legislative outcomes, common sense tells us not to expect much production from our lawmakers.

But we would be wrong.

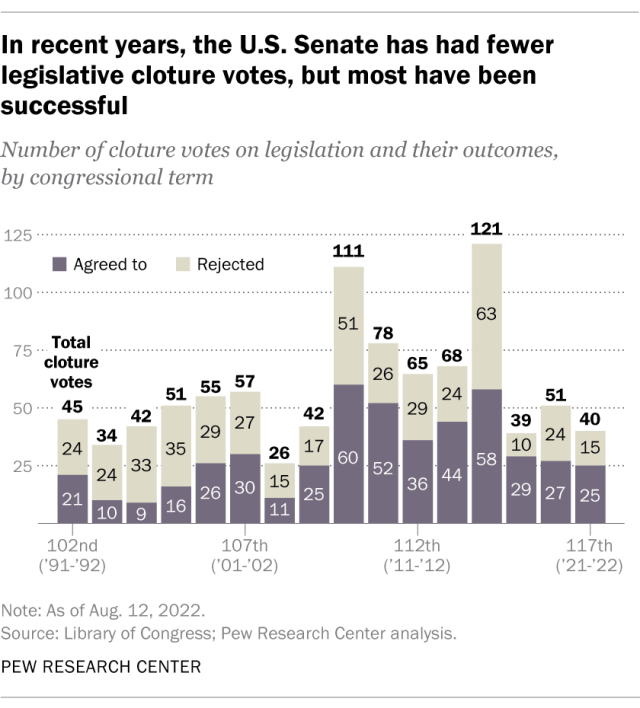

According to data compiled by the Pew Research Center, the current Senate has taken the second fewest cloture votes on legislation since 2005-06 (with an unusually high rate of success) and this Congress is on pace to pass more legislation than most of its predecessors over the past decade.

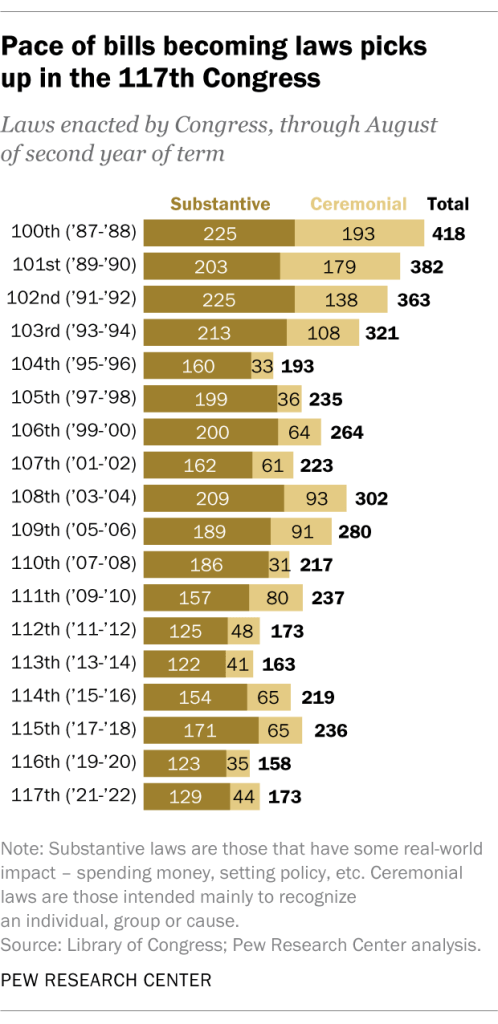

Congress has received some unusually positive publicity in recent months for passing a series of laws with bipartisan support, including an infrastructure package, a bill providing new health benefits for veterans, and a gun violence bill. While those bills deserve to get the headlines, the numbers show progress on much more.

Pew gathered data on the number of bills passed through August of the second year of each Congress’ two-year term. Pew further broke the totals down into “substantive” bills (such as spending and policy-setting measures) and “ceremonial” bills that honor individuals, groups or organizations.

The 117th Congress has passed 129 such substantive bills so far, up from 123 in 2019-20. Only the 114th (2015-16) and 115th (2017-18) Congresses passed more in the past dozen years. Republicans controlled both chambers during those four years, with comfortable margins in the House.

While the House can pass legislation with a simple majority vote, things are more complicated in the Senate. Yes, the Senate also passes legislation by majority, but the minority party – or even an individual senator – has the power to slow the process and even prevent passage of policy measures through the filibuster.

Before the Senate can vote on a bill, it must first vote to end debate on the measure (known as “cloture”). That motion requires 60 “yes” votes. In theory, lawmakers seeking to prevent cloture must keep speaking through the debate, but the Senate has evolved in a way that allows for a silent filibuster, in which the mere threat is enough to block passage.

The filibuster has been prominently used in the past few years to block legislation intended to establish national standards for election: the For the People Act, and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and the Freedom to Vote, which merged elements of the other two after they were blocked.

So far in the current Congress, the Senate has taken 40 cloture votes – one more than the 115th (2017-18). The last time there were so few cloture votes was 2003-05, which featured 26 such votes. Among the 40 votes, 25 (or 63 percent) were successful in ending debate and advancing to a final vote. That success rate is the fourth highest in the past 16 Congresses.