A Maryland law intended to prevent foreign election interference by regulating online political advertising has been struck down by a federal appeals court.

At a time when controlling the surge of misleading campaign spots on social media and news sites has proved easier said than done, Maryland was the first state to expand disclosure mandates. Its General Assembly enacted a law in time for the closing months of the 2018 midterm campaign requiring such platforms to publish information about ad purchases and keep records for the state to review.

But a three-judge panel of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals says the law unconstitutionally singles out political expression for special scrutiny and promises a "chilling effect" on free speech. The unanimous ruling on Friday, upholding a federal trial judge's position, is the latest in a series of federal judicial decisions against efforts to regulate campaign financing.

The decision could complicate efforts, which have stalled in Congress again this year, to subject online paid political advertising nationwide to the same disclosure and disclaimer regulations as TV and radio spots. The bill, known as the Honest Ads Act, has significant bipartisan support but GOP Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is unalterably opposed.

Nine newspapers that cover Maryland, including The Washington Post and The Baltimore Sun, successfully argued the law violates the First Amendment. More than a dozen news organizations supported the lawsuit.

In defending the statute, the Board of Elections maintained it was written only with electoral transparency in mind and does not infringe on the rights of the press to exercise editorial control and judgement.

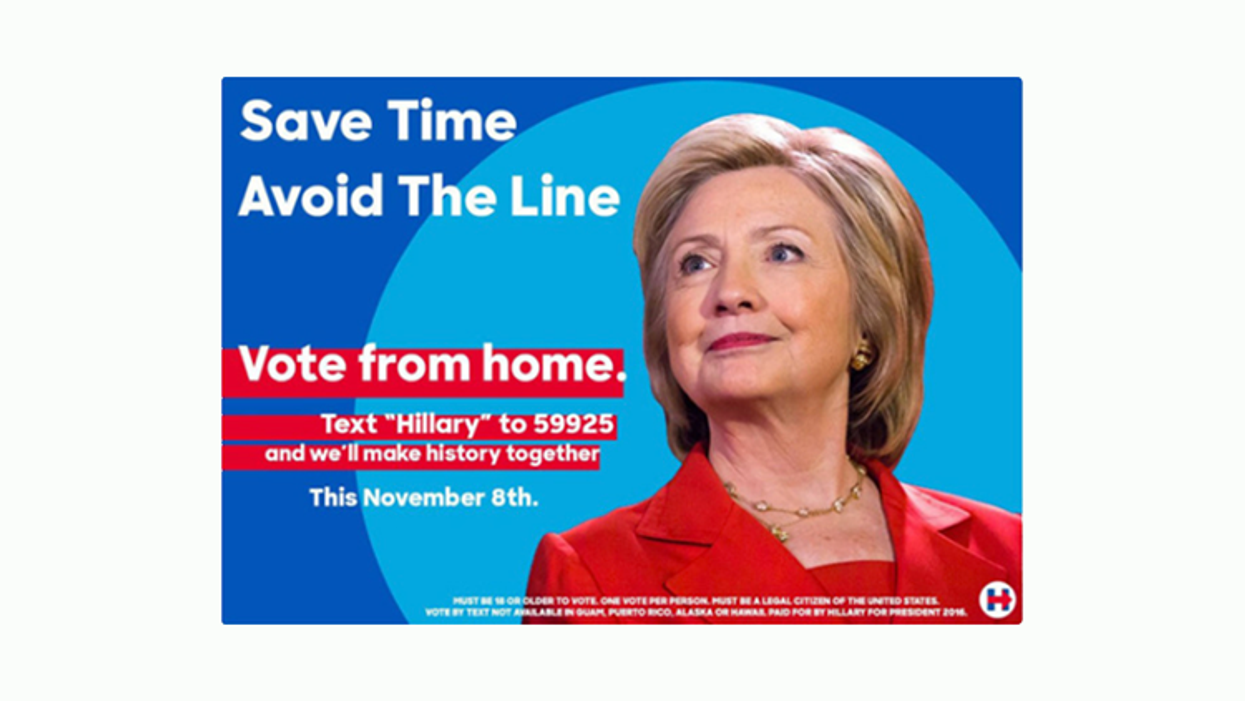

At the time the Democratic-majority Legislature wrote the measure, it was clear the policymakers of Annapolis were motivated by a desire to prevent a repeat of the sort of online misinformation campaigns by Russians and others that sullied the 2016 election. (GOP Gov. Larry Hogan raised free speech concerns but allowed the bill to become law without his signature.)

"Despite its admirable goals, the act reveals a host of First Amendment infirmities: a legislative scheme with layer upon layer of expressive burdens, ultimately bereft of any coherent connection to an offsetting state interest of sufficient import," Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III wrote for the court.

The law required online platforms that hosted political spots to maintain records of the buyer identities and contact information, the person exercising control over those entities and the total amounts paid for each ad.

Online platforms were also ordered to keep detailed records about the content of the ads for inspection by the Board of Elections. The records had to include the candidate or ballot issue the ad referred to, whether the ad was supportive or opposing, a description of the geographic locations where the ad was disseminated and a description of the audience that received or was targeted to receive the ad.

The court cited Google's decision to stop hosting political ads in Maryland last year as one example of the law's "chilling effect." Several other publishers promised to do the same if the law was upheld. At least one candidate for the state House claimed Google's withdrawal harmed his campaign.

"In sum, it is apparent that Maryland's law creates a constitutional infirmity distinct from garden-variety campaign finance regulations," Wilkinson wrote.