Your internet access is dependent on the security and resiliency of garden-hose-sized underwater cables. More than 800,000 miles of these cables criss-cross the oceans and seas. When just one of these cables breaks, which occurs about every other day, you may not notice much of a change to your internet speed. When several break, which is increasingly possible, the resulting delay in internet connectivity can disrupt a nation’s economy, news and government.

If there were ever a bipartisan issue it’s this: protecting our undersea cable system.

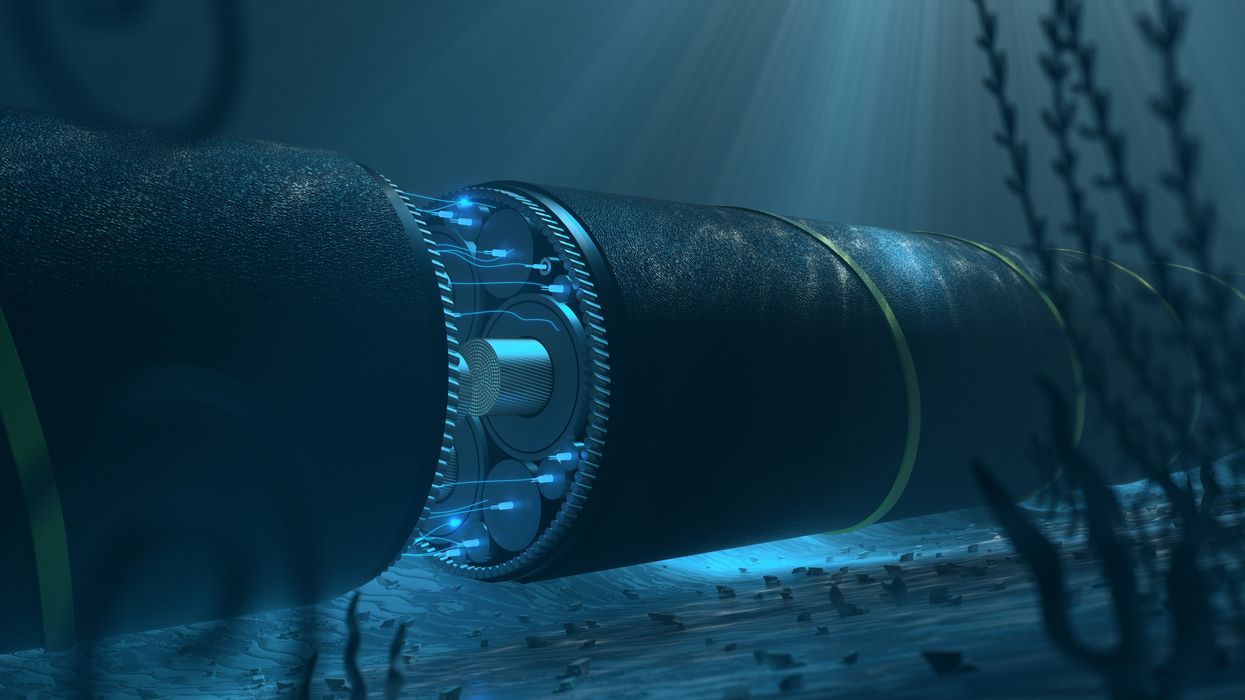

Nearly all internet traffic goes through this cable system. The fiber optic glass at the core of the cables allows the internet to operate at incredible speeds. The alternative — relying on satellites — is nearly five times slower. That’s why protecting these cables is essential, especially for countries with fewer cables.

The hundreds of cable systems around the world are not equally distributed. Whereas the United States has dozens and dozens of cables on both coasts, some countries have less than a handful, or none at all. Those latter countries are especially vulnerable to diminished internet upon a cable break. Take, for example, Japan in 2011. The tsunami that struck the island nation caused seven of its 12 transpacific cables to break. If one more cable had been severed, internet traffic between Japan and the U.S. may have come to a halt.

Reducing the vulnerability of this system is not easy. It’s not a matter of governments simply laying more cables. For lack of a better phrase, governments are not in the cable laying business. Nearly all undersea cables are privately owned. Microsoft, Meta, Google and Amazon are the ones laying cables at a historically unprecedented rate.

It’s also not as simple as sending out more repair ships. There’s only a couple dozen ships outfitted to repair cables. This small fleet is made up of a small, aging labor force.

Finally, it’s not as straightforward as hiding cables from bad actors who might want to intentionally break them. Making cables harder to find might actually increase the number of breaks. The plurality of breaks are caused by fishers accidentally dropping nets, anchors and other equipment on cables. If fishing boats do not know where cables are laid, they may cause breaks on an even more frequent basis.

All potential ways to make the undersea cable system more resilient come with tradeoffs. New Zealand and Australia, for example, have developed cable protection zones, in which all cables must fall. These zones decrease the odds of unintentional breaks by making more actors aware of cable locations. Yet, by concentrating cables in a single area, the odds of a single storm or bad actor causing several breaks increase. Cables made of more resilient material may withstand more severe storms, but upon a break may be even harder to repair. This is just a short list of proposals that come with pros and cons but merit more investigation.

While the next best step to protecting undersea cables is unclear, what’s obvious is that the status quo cannot persist. The public must make this an issue. Elected officials on both sides of the aisle ought to prioritize this critical infrastructure. And, cable owners like Google should embrace the public service they are performing by making the cable laying and repair process more transparent and participatory. That’s a tall order for each set of actors; it’s also one that should inspire and motivate us all to rally in defense of the undersea cable system.

Frazier is an assistant professor at the Crump College of Law at St. Thomas University and a Tarbell fellow.