Frazier is an assistant professor at the Crump College of Law at St. Thomas University. Starting this summer, he will serve as a Tarbell fellow.

There’s a handful of folks who argue that this is the best time to be alive in all of history. They have some compelling statistics to support that lofty claim. For instance, life expectancy is up; poverty is down; education is trending in the right direction; and deaths by violent conflict are generally declining. I’m sure that supporters of this argument could cherry pick a bunch of other statistics to add to that already impressive list. It would also be a waste of their time because they’re asking the wrong question.

Rather than ask if stats commonly associated with a good life are on the right track, we should be assessing if we’re living up to our potential — in other words, are we doing the most we can with all we’ve got? The answer to that question is an unequivocal “No.” And that answer should motivate us all to start exploring why we’re falling short of our collective capacity to do a lot more good for a lot more people.

Those focused on well-being statistics are akin to those who think whoever can hit a golf ball the furthest is the best golfer of all time. Unsurprisingly, this stat is always going to result in a contemporary golfer being the best — after all, they have better clubs and balls, improved health routines and mountains of analytics to develop the optimal swing. This stat also misses out on assessing how much better the golfer could be — an analysis that would require looking at a broader set of statistics and, most importantly, looking at the player’s capacity and willingness to improve.

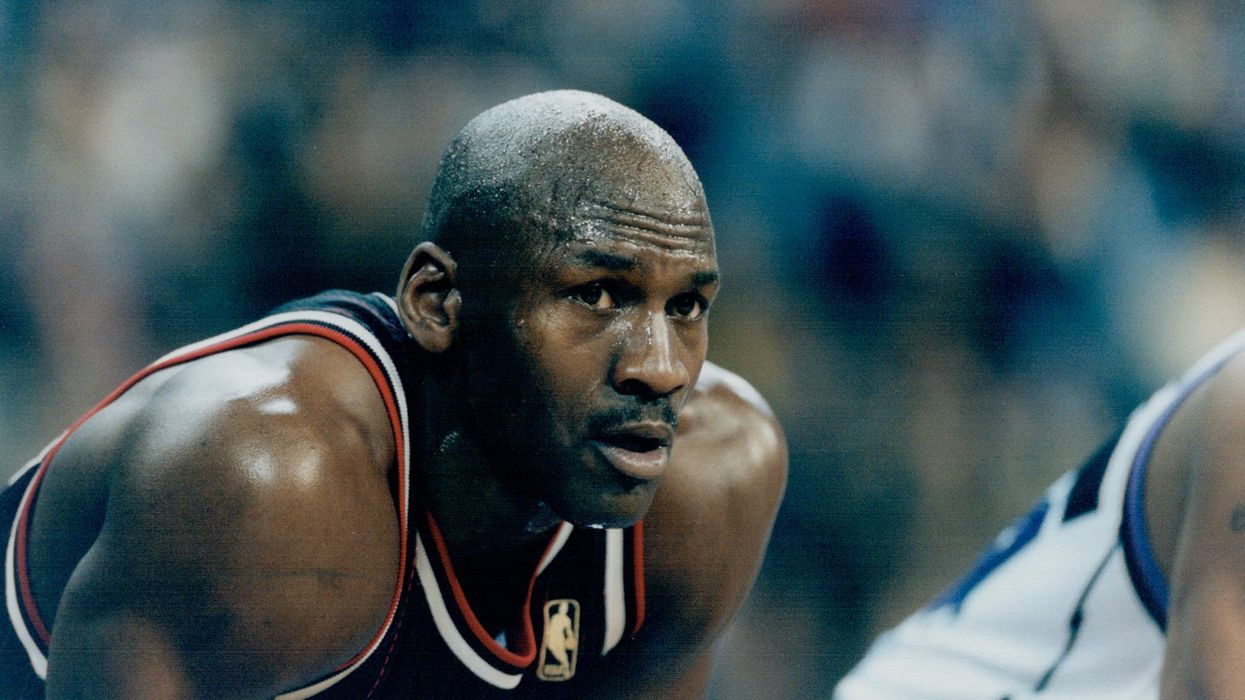

What makes Tiger Woods the greatest golfer of all time isn’t the number of titles he’s won or clutch putts he’s sunk —it’s the fact that he has used every single opportunity afforded to him to better his game. To keep the sports analogy going, Michael Jordan is the GOAT despite LeBron James holding the NBA scoring title and other players having more championship rings. MJ created a culture of success that turned teams with OK talent into winning machines.

As of 2024, we’ve got more resources, knowledge and technology than at any other point in human history. Yet, we’re falling woefully short of putting those advantages to their proper and most impactful use. Let’s consider a few examples,

First, let’s look at our cities. We have all the building materials, land and architectural ingenuity to construct safe, reliable housing for all residents; yet, homelessness is pervasive and seemingly a permanent problem. Next, let’s think about rural communities that still lack basic internet access; again, we have the technology and resources to provide every American with access to high-speed internet, which would allow them to access educational opportunities and schedule telehealth appointments. Finally, let’s look beyond our borders. Thanks to scientific advances, we can reliably predict when and where famines will likely occur; yet, these crises are often unaddressed or at least not addressed to the extent they should be.

This sort of analysis helps explain why folks around the world have grown skeptical of their governments. The unhoused, the digitally disconnected and the famished are justifiably not celebrating the fact that, on average, humans are living longer. Folks who find themselves in any of those situations know that we can and should be doing a lot better; we all need to recognize that “progress” on hand-picked statistics isn’t the same as “progress” as a society.

A society that lives up to potential is constantly exploring how best to put its resources to their full use in order to improve collective well-being. This proactive search is missing in a lot of our contemporary policy conversations. Too often we’re discussing how to maintain the status quo rather than stepping back and asking if the way things are is the way things ought to be. This isn’t to say that we should upend society in the course of the day — that wouldn’t be productive either. Instead, we merely need to be looking for ways to incrementally improve.

Instead of marveling at all the tools in our toolkit — all the progress that we’ve allegedly made, we should be debating and planning how best to use those tools. Then and only then can we say we’re living up to our potential.