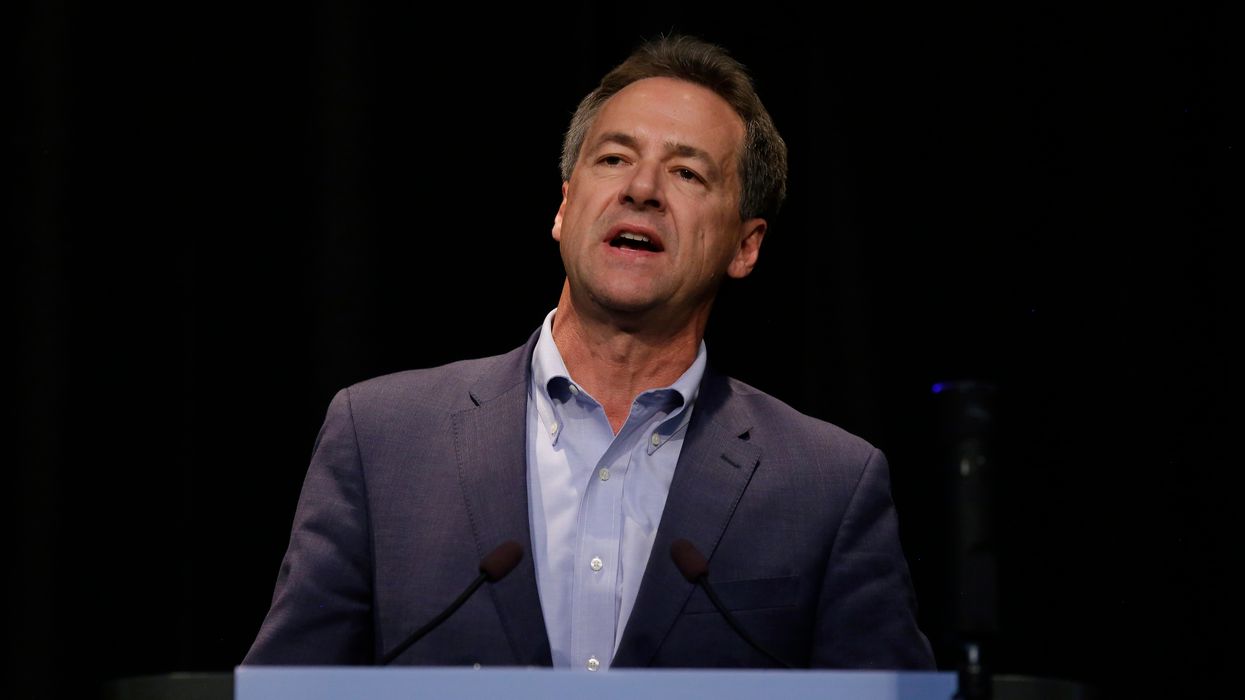

Gov. Steve Bullock is giving county election officials across Montana permission to conduct the general election entirely by mail, as they did for the June primary.

The governor, who will be on the November ballot as the Democratic candidate for the Senate, said Thursday he was issuing the order at the request of the county clerks and election administrators. During the all-mail primary, the state saw a surge in voter turnout.

California, Nevada, Vermont and Washington, D.C. have already opted to send each voter an absentee ballot this fall due to the coronavirus. Before the pandemic, five other states — Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington — already had plans to conduct an all-mail election.

Bullock's directive still requires counties to make in-person voting available if they choose to conduct the election primarily by mail. Absentee ballots will be sent by Oct. 9 with return postage paid.

"It only makes sense that we start preparing now to ensure that no Montanan will have to choose between their vote or their health," Bullock said. "They didn't have to in June and they shouldn't have to in November."

All 56 counties opted for an all-mail primary in June, and it's almost certain they will do the same for the general election. The primary saw the highest rate of voter participation in almost 50 years, with 55 percent of registered voters returning ballots — 10 percentage points higher than the 2016 primary.

Bullock is in a highly competitive race against Republican incumbent Steve Daines, who is seeking a second Senate term. President Trump — who has spent months asserting without evidence that expansive mail voting leads to fraud — is likely but not a lock to carry the state's three electoral votes, according to recent polls. The last Democrat to carry the state was Bill Clinton in 1992.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room