New York's new public campaign finance system and rules limiting the power of small political parties were struck down Thursday, a state judge ruling their creation by an independent commission last year violated the state Constitution.

A package with both provisions took the force of law in January under an unusual procedure in which the Legislature's choices were to either reject it or let it happen. That was "an improper and unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority," Niagara County Supreme Court Justice Ralph Boniello ruled.

Third parties hailed the ruling, which preserves their candidates' relatively easy access to spots on the ballot in the nation's fourth most-populous state. Advocates of reducing big money's sway over campaigns, meanwhile, said there was plenty of time to recover. The new taxpayer matching funds were not going to start flowing for six years — allowing plenty of time for the system to get enacted the usual way.

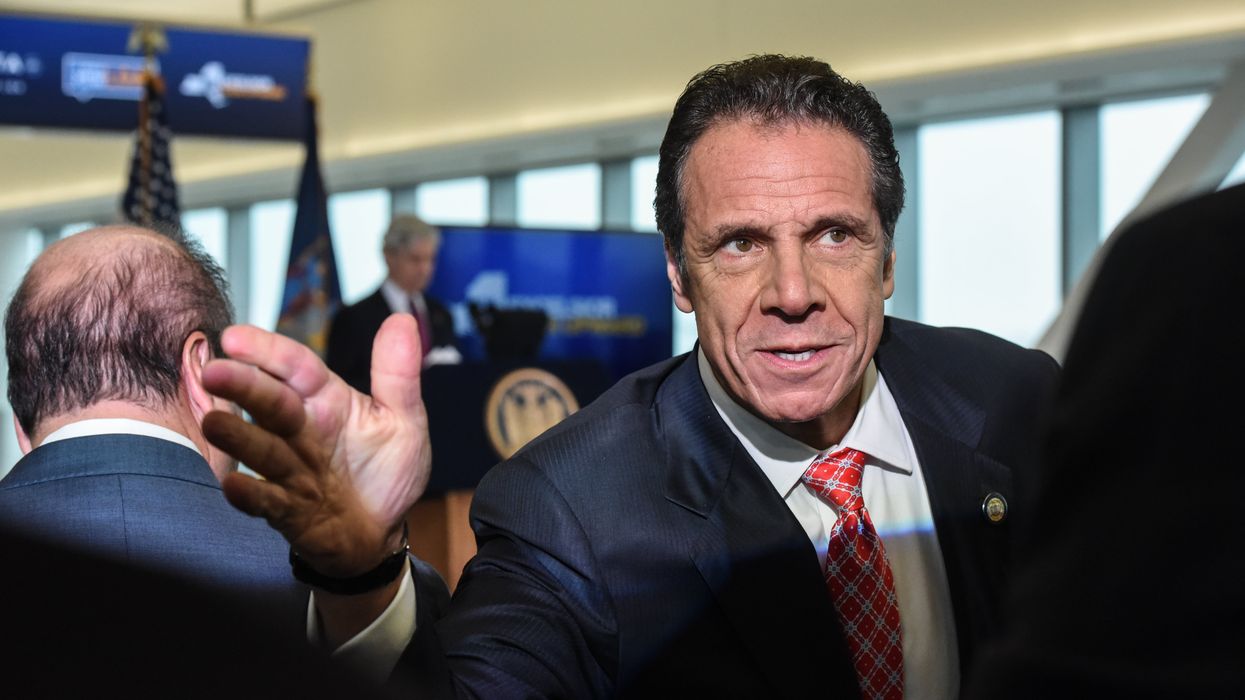

"Albany can't use today's court ruling as an excuse to derail a public financing program that was promised to New Yorkers," said Lawrence Norden of the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law, one of the most prominent groups pushing the overhaul. All legislative leaders and Gov. Andrew Cuomo need to do, he said, is enact "the law the commission drafted after months of public testimony and expert input, which includes features that could make it a model for reform across the nation."

After the state government in 2019 came under total Democratic control for the first time in the decade, however, the political leadership failed to agree on such a package — deciding instead to turn the negotiations over to a specially appointed Public Finance and Elections Commission.

The plan those nine panelists came up with in November would use taxpayer money to amplify contributions of up to $250 to candidates for statewide offices and the Legislature, with a 12-to-1 match for the smallest donations and 9-to-1 for a $250 gift. In addition, the contribution cap for a statewide candidate was to drop to $18,000 — still among the highest in any state, although a fraction of current limits that run as high as $69,700 for some races.

Part of the deal-making was a huge victory for a commissioner named by Cuomo, state Democratic chairman Jay Jacobs. He got language in the package nearly tripling — to 140,000 from 50,000 — the number of votes minor-party candidates would have to get in each statewide election to preserve their right to a line on the ballot for the next four years.

The only parties for which this would be no problem are the Republicans and Democrats, who routinely draw more than 2 million votes each, even in a lopsided contest. The Conservative Party has crested the number sometimes, but not any of the state's other minor parties.

The new requirements, which were to take effect for the 2024 election, are now scrapped unless they reappear in a future legislative package.

"This ruling is a victory for the voters of New York State. We need more choices, not fewer, to build a strong democracy," said Sochie Nnaemeka of the progressive Working Families Party, which has been a frequent nemesis of the Cuomo administration and was one of the plaintiff's in the lawsuit.

Jerry Kassar of the Conservatives said the ruling proves that the commissions' decisions were "total overreach by an overzealous governor" and called it a "victory for political freedom."

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift