Efforts to drain more politics out of legislative mapmaking for the new decade are getting pride of place as GOP-run legislatures convene in a pair of generally red Midwestern states.

Influential lawmakers from both parties in the Indiana General Assembly signed a pledge Monday to support legislation making the next round of redistricting more transparent, nondiscriminatory and politically impartial than in the past.

And in Missouri, where the General Assembly convened on Wednesday, leaders of the GOP majorities are pushing a measure they describe as a compromise for tamping down the state's past tendencies toward partisan gerrymandering. Democrats are not yet on board, however.

Legislative and congressional district lines across the country get redrawn once a decade, the year after the census details how the population has changed and relocated, to reflect the Constitution's one-person, one-vote mandate.

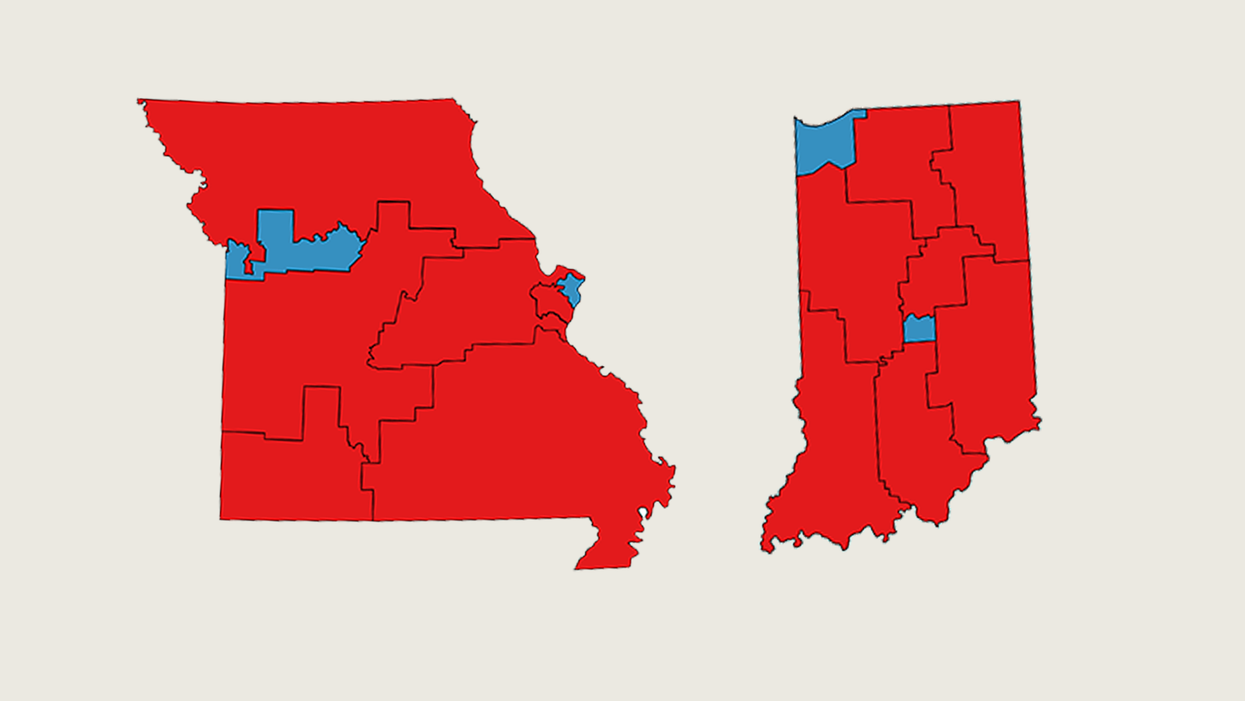

Under the maps that were in use for the past decade and will be used for the last time this fall, the GOP has a comfortable hold on seven of the nine U.S. House seats in Indiana and six of the eight districts in Missouri, along with supermajorities in both halves of the legislatures in both states. But in the last statewide races in both places, for Senate seats in 2018, Republicans Mike Braun of Indiana and Josh Hawley of Missouri each defeated incumbent Democrats with just 51 percent of the vote.

The redistricting reform bill on the agenda in Indianapolis with the best chance of passage would allow citizens to access the detailed census data so they could try their hand at drawing political boundaries — and would require, at least theoretically, the legislators to take such handiwork into account when setting the real lines.

"Legislators should serve in competitive districts," GOP Sen. John Ruckelshaus said in unveiling the bill and its bipartisan roster of sponsors this week. "I think we're all better for that. Competition is good."

He conceded, however, that his more ambitious measure — to turn the redistricting responsibilities over to an independent commission — was not likely to advance any farther this time than the previous two times he's offered it, which was nowhere.

In Missouri, by contrast, 62 percent of voters in 2018 approved redistricting changes as part of a sweeping constitutional amendment. It created a new position in Jefferson City for a nonpartisan state demographer, with responsibility for proposing state House and Senate maps after the 2020 census with the goals of achieving both "partisan fairness" and "competitiveness." Six finalists are still in the running.

Some Republicans are pushing for having the state vote to change the system again this fall — so that the demographer's work next year would be subject to approval by the same bipartisan (but GOP-tilted) commission that drew the lines a decade ago. Some Democrats are willing to go along but others say that would undercut the point of the referendum two years ago.![]()

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift