So, if this were a normal presidential election year, the country would already be focusing its attention on the next big event in the life cycle of our democracy — Inauguration Day on Jan. 20, with Joe Biden being sworn in as the 46th American president.

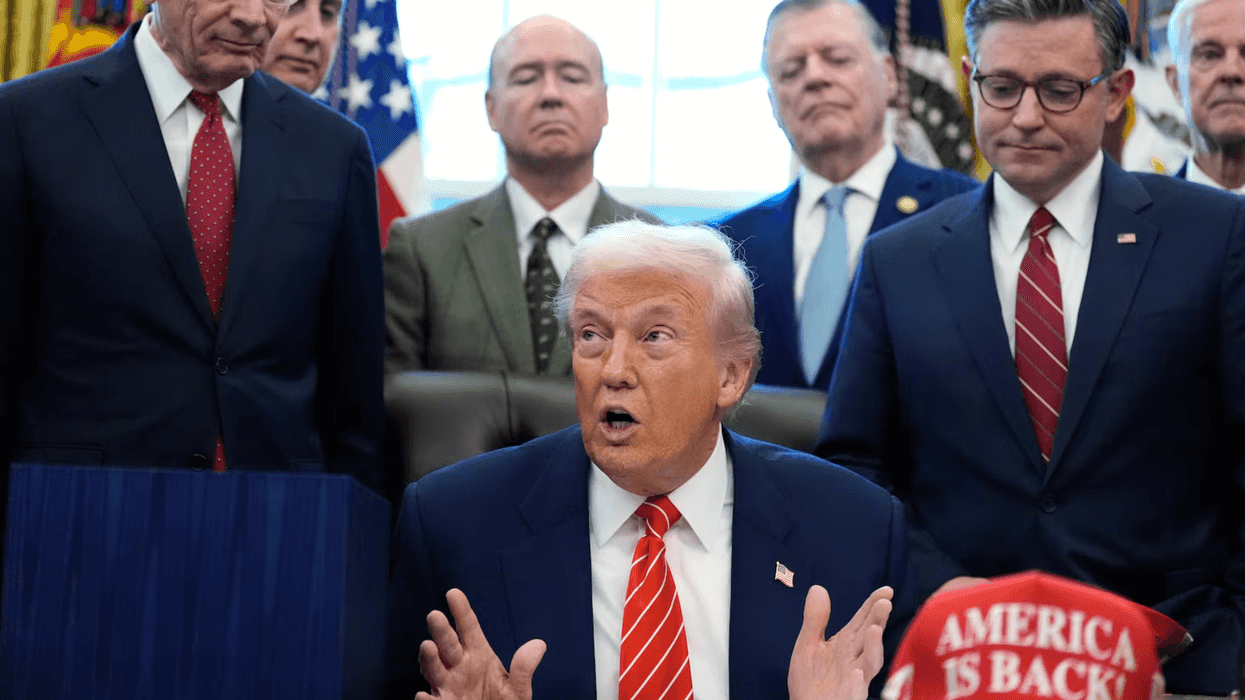

But almost nothing about this election has been normal, of course. Witness, most recently, President Trump's refusal to concede defeat in the face of overwhelming evidence he's lost decisively. And his stubbornness, buttressed by the passions of millions of fervent supporters and the passiveness of the Republican Party's other leaders, makes it important to understand the presidential contest's complicated path over the coming weeks.

One way to think about it is like a game with really arcane rules but a usually predictable outcome: "Win the Electoral College." The players move their pieces along the right path, hoping to reach the finish without taking dangerous side trips that set them back along the way.

Usually it works that way, but not always — a bit like an analogous kids' game, "Chutes and Ladders." Here's what the board looks like:

Stop 1: Select the electors

Sometime earlier in the year the Republican and Democratic parties of each state (and the District of Columbia) chose people to be their slates of electors if their presidential and vice presidential ticket ends up carrying their state — one for each member of Congress (House and Senate) in that state. Except for Nebraska and Maine, the states use the winner-takes-all approach for awarding their electoral votes. (In those states, two electoral votes go to the popular vote winner statewide and one to the vote winner in each congressional district.)

Stop 2: Ascertain the vote

As soon as possible after Election Day, officials in each state prepare "Certificates of Ascertainment" listing the electors who correspond to the winner of the popular vote. Each state prepares multiple copies of these documents. One goes to the Archivist of the United States. The state's have an incentive to get any disputes resolved by Dec. 8, which is considered under federal law as the "safe harbor" deadline. That means the results agreed to by then are considered conclusive.

Stop 3. Electors meet and vote

On Dec. 14, the electors are to gather in each state to cast their votes for president and vice president. The electors vote by paper ballot. They record the totals on Certificates of the Vote, which are paired with the Certificates of Ascertainment and sent to the president of the Senate — in this case, Mike Pence, the GOP candidate for another term as vice president.

Possible side trip 1

Here is the first point where the process could go down a chute. Some conservatives argue the Constitution allows for state legislatures to substitute their own slate of electors for those supporting the will of the most voters in the state. Since Republicans control the legislatures in all four battlegrounds that Biden has carried (or looks destined to carry) by less than 1 percentage point — Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, with a combined 57 electoral votes — they could argue the results are tainted by fraud or irregularities and that unprecedented moves are warranted to assure the re-election of Trump as the rightful winner.

Wrong, say a whole slew of legal experts and Biden backers. Even the urban-legend-destroying website Snopes has concluded this strategy is a no-go. The key, they say, is that Article II of the Constitution allows state legislatures to decide "the manner " in which electors are chosen. But if they were going to do that, many election lawyers say, it had to be done prior to Election Day — and since all these states have decided that the popular vote determines the slate of electors, it's too late to change now.

Adav Noti, senior director at the Campaign Legal Center, dismissed the idea of GOP legislatures going rogue. "It shouldn't be a serious topic of discussion," he said. But Ned Foley of Ohio State's law school seemed to give the strategy some credence while decrying it at the same time in a widely circulated op-ed.

Possible side trip 2

Some assert that no law explicitly requires the electors chosen to represent one party's nominees must actually vote for those people. So, the argument goes, Republicans could try to win over some electors who seem committed to vote for Biden and his running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris.

This argument has many challenges — starting with how rare so-called faithless electors have been: Ten voted or tried to vote for somebody they were not supposed to last time, but just nine did so in all the other 17 elections since World War II. Second, Biden's probable margin of victory in the Electoral College is 74 votes, an enormous hurdle for a rogue group to overcome. Finally, five states have penalties for a deviant voter, and 14 allow a faithless elector's ballot to be tossed and the elector replaced — laws the Supreme Court upheld unanimously this summer.

Stop 4: The votes are counted

At 1 p.m. on Wednesday, Jan. 6, the members of the newly elected Congress will gather in a joint session and listen as the electoral votes are announced by state in alphabetical order. When the count is complete, the presidential and vice presidential winners will be announced by the presiding officer — Pence, once again.

Possible side trip 3

Members of Congress have the right to object to the electoral votes as they get announced. For an objection to be considered, though, it has to have the support of at least one House member and one senator. According to precedent, the only objections that get considered concern electors who were not legally chosen or whose votes were not legally cast. Any objections Pence rules in order are taken up in separate meetings by the House and Senate, who have no fixed deadlines for their deliberations. No electors can be rejected unless both the House and Senate agree. Given that Democrats control the House, that is not going to happen. Plus, the laws governing the challenges set up a presumption in favor of the legality of a state's electors.

So, there you have it. A smooth transition to a new administration or a knock-down, drag-out fight. Which do you expect?

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room