Johnson is executive director of Election Reformers Network, a nonprofit founded by international election specialists now supporting reform in the United States.

Our historical cousins in the United Kingdom vote much like we do — in single-member districts, under simple plurality rules — so their elections are worth paying attention to. This is particularly true now that "the duopoly," the dominance of two parties characteristic of single-member-district systems, has become such a source of concern here in the United States.

The recent elections in the U.K. illustrate just how dominant a duopoly can be, even in a country with well-established third parties. More importantly, the elections illustrate that a new form of elections gaining prominence here, ranked-choice voting, will likely have only limited impact on reducing duopoly power, and that more significant reform means changing the single-member-district system itself, to the multimember approach called for in a bill before Congress dubbed the Fair Representation Act.

Single-member districts make life difficult for alternative parties, even those with reasonable support nationwide. A party with, say, an environment-first agenda, or a moderate-centrist platform, could poll relatively well nationally but not have enough supporters in any given district to win elections.

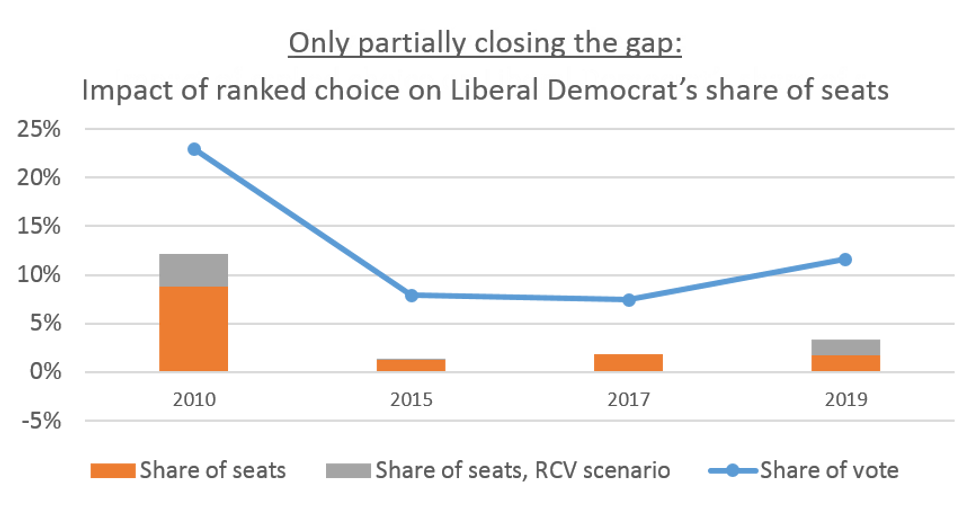

This pattern is clear in the track record of Britain's Liberal Democratic Party, which is the kind of centrist alternative often wished for in the United States. The Lib Dems have fielded candidates in most districts — or "constituencies" — for several decades and in 2010 entered government in coalition with the Conservative Party. What the Lib Dems have not been able to do is translate voter support efficiently into seats in Parliament. In the eight general elections since 1992, the Liberal Democrats' 15 percent aggregate vote share has won only 5 percent of seats.

By contrast, in the same time period the two dominant parties have claimed more seats than their aggregate share of ballots: The Conservatives have taken 37 percent of the vote but won 42 percent of the seats, while Labor, with 36 percent of the vote, has gained 46 percent of the seats.

In the elections in December, the pattern intensified: The Lib Dems gained only 2 percent of seats despite receiving nearly 12 percent of the vote, and the Conservatives, with 44 percent of the vote, won an absolute majority of 55 percent in Parliament.

Here in America we don't have the same range of parties — in part because our Congress is undersized, with only one-seventh the number of representatives per citizen as Britain. But we do have political groupings that have trouble gaining representation in proportion to their share of the population. This is true of course of ethnic minorities, and it's also true of categories like rural populations, Republicans in New England, Democrats in the Great Plains and many others. Our country is a dense patchwork quilt of significant minorities covered over by the all-too-familiar swaths of red and blue, monochromatic blocks that fundamentally are rounding errors.

Isn't this the problem that ranked-choice voting is designed to fix? Not exactly. RCV can mean different things, but in its well-known form today, it gives voters the opportunity to rank their preferences within single-member-district elections, and thus has limited impact on underrepresentation across a nation of single-member districts.

We can judge whether RCV would have changed the most recent outcome in the UK from exit polls that ask voters for second and third choices. As the chart below illustrates, RCV would give Liberal Democrats more seats on average, but it would not fundamentally address the underrepresentation relative to their share of the vote.

2019 estimate by Election Reformers Network Source: Electoral Reform Society

2019 estimate by Election Reformers Network Source: Electoral Reform Society

To be clear, ranked-choice voting has a lot to offer to American voters and political parties, and is particularly needed as we experience a major increase in multicandidate elections. RCV almost always ensures the most supported candidate wins and gives voters the freedom to support longshot candidates without "spoiling" the results. Our research has found greater extremism among House members who get to Congress after a low-plurality primary win in a district that's "safe" for their party — an outcome RCV would prevent. RCV tends to encourage cooperation and reduce negative campaigning.

What RCV can't do, however, and although some hope it could, is transform our duopolistic politics by significantly expanding representation. For that, we need a system that gives seats to candidates who have strong but not majority support. And that means moving away from single-member districts.

For Congress, the best alternative is the Fair Representation Act, through which we would elect three to five House members from each district using a form of RCV called single transferable vote. This approach is favored by leading organizations in the U.K. including the prestigious Electoral Reform Society. Analyses show it would have made for much closer correlation between the share of votes and share of seats in prior U.K. elections.

In this country, the proposed Fair Representation Act has the significant added benefit of addressing gerrymandering, both because it calls for district lines to be drawn by independent commissions and because it would entail many fewer districts.

With multimember districts, the country's alternative parties would gain new life. The nature of politics between our dominant parties would change, as a candidate from the minority party would likely gain at least one seat in most districts, revealing the true patchwork quilt hiding behind those blocks of red and blue. And the system would boost diversity, bringing more women and people of color to the Capitol.

Still, the idea has not yet gained the attention it deserves among reform organizations. The relative simplicity and hip appeal of RCV may account for this in part, along with the preference among reform groups for nearer-term achievability.

The Fair Representation Act will not be an easy win. It will require a majority in Congress willing to change a system from which they have benefitted. But the place is dangerously broken and impossible to fix without such a change.