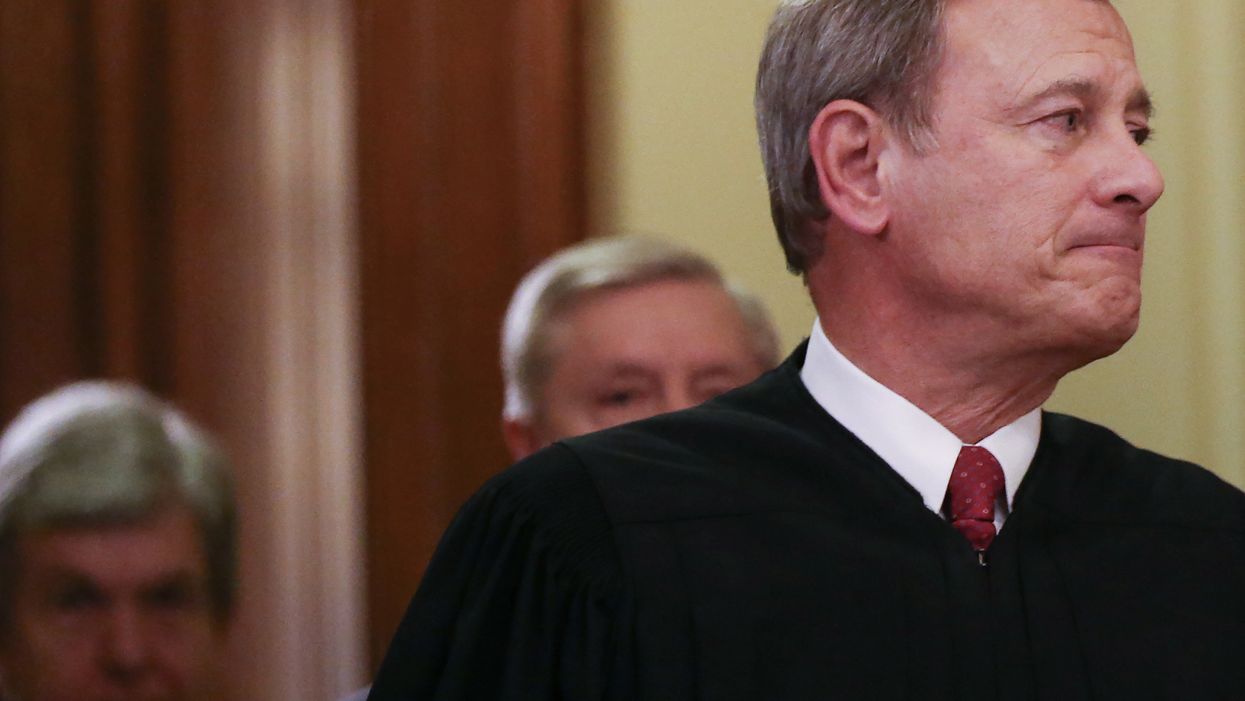

In less than two weeks, Chief Justice John Roberts has delighted liberals and infuriated conservatives by joining the majority in three of the year's biggest cases.

On Monday he agreed to strike down Louisiana's highly restrictive abortion law. Days eralier he decided to uphold protections for young undocumented workers known as Dreamers, and to bar job discrimination against gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender workers. Two of his votes were decisive and the third one may effectively have been, since it's unclear Justice Neil Gorsuch would have been ready to stand alone against his conservative brethren in the LGBTQ case.

Constitutional law professors and analysts have been parsing precedent and otherwise trawling jurisprudence to speculate on the reasons for what seems atypical behavior, but few have yet to explore the possibility that the explanation does not lie in jurisprudence at all.

Supreme Court eras are always discussed and evaluated in terms of the chief justice. The Marshall Court and the Taney Court were the most memorable ones in the 19th century, and the Warren Court reshaped the nation in the 1950s and '60s. Now, it will be the Roberts Court.

And he bears a burden that even the most prominent associate justices — Oliver Wendell Holmes or John Marshall Harlan, Antonin Scalia or Ruth Bader Ginsburg — never have. As Roberts noted ruefully in a 2017 interview: "It's sobering to think of the 17 chief justices; certainly a solid majority of them have to be characterized as failures."

The fact that the most historic cases — from Marbury v. Madison (John Marshall) to Dred Scott v. Sandford (Roger Taney) to Brown v. Board of Education (Earl Warren) — are inextricably linked with their presiding officer perhaps explains why Roberts previously refused to be identified with dismantling the Affordable Care Act. (In the most consequential and polarizing opinion of his early years, he wrote the 5-4 majority decision upholding Obamacare back in 2012.)

This is not the role he sought. A naturally collegial man, Roberts prides himself on both adhering to the law and bridging ideological divides.

"If I'm sitting there telling people, 'We should decide the case on this basis,' and if you, another justice, think, 'That's just Roberts trying to push some agenda again, and if it were more of a different result that he didn't like then he wouldn't be saying it," they are not likely to listen very often," he told constitutional scholar Jeffrey Rosen for his book on the court.

In that interview, when Roberts had been in the chief's job less than two years, he venerated his legendary predecessor Marshall and spoke glowingly of his ability to promote harmony by being "convivial," and taking "great pride in sharing his Madeira with his colleagues."

To be worthy of walking in Marshall's footsteps, Roberts vowed, he intended to use his power to achieve as broad a consensus as possible.

Still, although he may genuinely believe he lacks an ideological agenda, Roberts most definitely does not lack an ideology. He has in the past, with few exceptions, been predictably and reliably conservative — as in Citizens United v. FEC, the decision that opened the floodgates of campaign cash a decade ago. And he has almost always deferred to the wishes of Republican presidents.

But this Republican president is like no other. There can be little question that with Donald Trump in the White House, the nation has been sliding toward dictatorship. Vitriolic attacks on an independent judiciary have been numerous, and what Republicans formerly praised as "the rule of law" has been quickly disappearing.

Roberts is thus in an increasingly fraught position.

If he personally perceives Trump as a threat to fundamental democratic institutions, as the president himself seems to want to be, does the chief justice decide he must use the Supreme Court's power to protect those institutions?

Or does he look the other way and defer? As such a self-described "keen student of constitutional history" is doubtless aware, whatever course Roberts chooses — enabler or opponent — will have a significant impact on his legacy.

To date, he has chosen generally to remain conservative — although he has occasionally bounced across the ideological divide to demonstrate that both he and the court are fair. But the political landscape has suddenly and drastically changed, and these past few weeks just may mark the moment when the chief justice decided that the nation is under sufficient threat that he must use the judiciary's power to stop it.

The stakes are enormous because the court will undoubtedly be forced to rule on a number of voting rights cases, which could well determine the outcome of the election in November. Florida and Iowa have been pursuing initiatives to add financial requirements that prevent felons from voting after their release from prison. And other states, including Georgia, Texas, and Wisconsin, have initiated voter identification requirements widely recognized as attempts to keep African-Americans from the polls.

These transparent attempts to desiccate Black voting smack of the Jim Crow South, where every state in the old Confederacy redrew its constitutions specifically to disenfranchise Black voters. To the shame of the court under Chief Justices Morrison Waite and Melville Fuller, between 1874 and 1910 the court used tortured logic and verbal gymnastics to permit blatantly discriminatory state laws to stand — helping doom the nation to decades of post-Reconstruction infamy.

With his four conservative colleagues almost certain to line up on one side of the question, only Roberts himself, already under a cloud for the gutting of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder seven years ago, can decide if the Roberts Court will do the same.

Visit IVN.us for more coverage from Independent Voter News.

Will Trump’s moves ever awaken conservatives?