Menczer is the Luddy distinguished professor of informatics and computer science at Indiana University.

An internal Facebook report found that the social media platform's algorithms – the rules its computers follow in deciding the content that you see – enabled disinformation campaigns based in Eastern Europe to reach nearly half of all Americans in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, according to a report in Technology Review.

The campaigns produced the most popular pages for Christian and Black American content, and overall reached 140 million U.S. users per month. Seventy-five percent of the people exposed to the content hadn't followed any of the pages. People saw the content because Facebook's content-recommendation system put it into their news feeds.

Social media platforms rely heavily on people's behavior to decide on the content that you see. In particular, they watch for content that people respond to or "engage" with by liking, commenting and sharing. Troll farms, organizations that spread provocative content, exploit this by copying high-engagement content and posting it as their own.

As a computer scientist who studies the ways large numbers of people interact using technology, I understand the logic of using the wisdom of the crowds in these algorithms. I also see substantial pitfalls in how the social media companies do so in practice.

From lions on the savanna to likes on Facebook

The concept of the wisdom of crowds assumes that using signals from others' actions, opinions and preferences as a guide will lead to sound decisions. For example, collective predictions are normally more accurate than individual ones. Collective intelligence is used to predict financial markets, sports, elections and even disease outbreaks.

Throughout millions of years of evolution, these principles have been coded into the human brain in the form of cognitive biases that come with names like familiarity, mere exposure and bandwagon effect. If everyone starts running, you should also start running; maybe someone saw a lion coming and running could save your life. You may not know why, but it's wiser to ask questions later.

Your brain picks up clues from the environment – including your peers – and uses simple rules to quickly translate those signals into decisions: Go with the winner, follow the majority, copy your neighbor. These rules work remarkably well in typical situations because they are based on sound assumptions. For example, they assume that people often act rationally, it is unlikely that many are wrong, the past predicts the future, and so on.

Technology allows people to access signals from much larger numbers of other people, most of whom they do not know. Artificial intelligence applications make heavy use of these popularity or "engagement" signals, from selecting search engine results to recommending music and videos, and from suggesting friends to ranking posts on news feeds.

Not everything viral deserves to be

Our research shows that virtually all web technology platforms, such as social media and news recommendation systems, have a strong popularity bias. When applications are driven by cues like engagement rather than explicit search engine queries, popularity bias can lead to harmful unintended consequences.

Social media like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok rely heavily on AI algorithms to rank and recommend content. These algorithms take as input what you like, comment on and share – in other words, content you engage with. The goal of the algorithms is to maximize engagement by finding out what people like and ranking it at the top of their feeds.

How social media filter bubbles workyoutu.be

On the surface this seems reasonable. If people like credible news, expert opinions and fun videos, these algorithms should identify such high-quality content. But the wisdom of the crowds makes a key assumption here: that recommending what is popular will help high-quality content "bubble up."

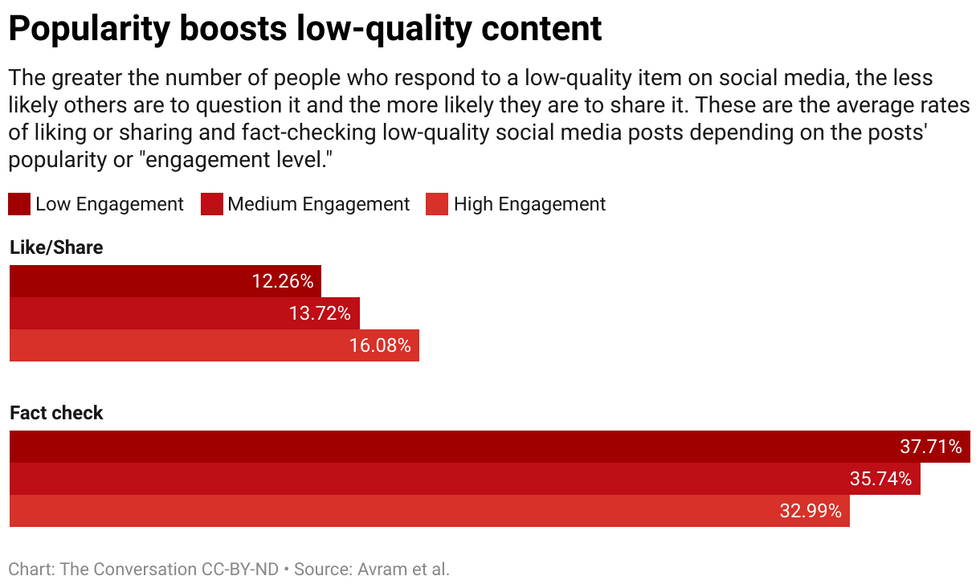

We tested this assumption by studying an algorithm that ranks items using a mix of quality and popularity. We found that in general, popularity bias is more likely to lower the overall quality of content. The reason is that engagement is not a reliable indicator of quality when few people have been exposed to an item. In these cases, engagement generates a noisy signal, and the algorithm is likely to amplify this initial noise. Once the popularity of a low-quality item is large enough, it will keep getting amplified.

Algorithms aren't the only thing affected by engagement bias – it can affect people too. Evidence shows that information is transmitted via "complex contagion," meaning the more times people are exposed to an idea online, the more likely they are to adopt and reshare it. When social media tells people an item is going viral, their cognitive biases kick in and translate into the irresistible urge to pay attention to it and share it.

Not-so-wise crowds

We recently ran an experiment using a news literacy app called Fakey. It is a game developed by our lab, which simulates a news feed like those of Facebook and Twitter. Players see a mix of current articles from fake news, junk science, hyperpartisan and conspiratorial sources, as well as mainstream sources. They get points for sharing or liking news from reliable sources and for flagging low-credibility articles for fact-checking.

We found that players are more likely to like or share and less likely to flag articles from low-credibility sources when players can see that many other users have engaged with those articles. Exposure to the engagement metrics thus creates a vulnerability.

The wisdom of the crowds fails because it is built on the false assumption that the crowd is made up of diverse, independent sources. There may be several reasons this is not the case.

First, because of people's tendency to associate with similar people, their online neighborhoods are not very diverse. The ease with which social media users can unfriend those with whom they disagree pushes people into homogeneous communities, often referred to as echo chambers.

Second, because many people's friends are friends of one another, they influence one another. A famous experiment demonstrated that knowing what music your friends like affects your own stated preferences. Your social desire to conform distorts your independent judgment.

Third, popularity signals can be gamed. Over the years, search engines have developed sophisticated techniques to counter so-called " link farms" and other schemes to manipulate search algorithms. Social media platforms, on the other hand, are just beginning to learn about their own vulnerabilities.

People aiming to manipulate the information market have created fake accounts, like trolls and social bots, and organized fake networks. They have flooded the network to create the appearance that a conspiracy theory or a political candidate is popular, tricking both platform algorithms and people's cognitive biases at once. They have even altered the structure of social networks to create illusions about majority opinions.

Dialing down engagement

What to do? Technology platforms are currently on the defensive. They are becoming more aggressive during elections in taking down fake accounts and harmful misinformation. But these efforts can be akin to a game of whack-a-mole.

A different, preventive approach would be to add friction. In other words, to slow down the process of spreading information. High-frequency behaviors such as automated liking and sharing could be inhibited by CAPTCHA tests or fees. Not only would this decrease opportunities for manipulation, but with less information people would be able to pay more attention to what they see. It would leave less room for engagement bias to affect people's decisions.

It would also help if social media companies adjusted their algorithms to rely less on engagement to determine the content they serve you. Perhaps the revelations of Facebook's knowledge of troll farms exploiting engagement will provide the necessary impetus.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Click here to read the original article.