While unprecedented numbers will vote by mail this year because of the pandemic, millions may be forced to put health concerns aside and show up at the polls — not because of restrictive rules or ballots delayed in the mail, but because they've lost their homes.

As a federal moratorium on evictions expires, about a third of renters who had been protected could face homelessness as soon as the end of the month. Even if they find a temporary place to live, many will miss registration deadlines or never see the absentee ballots they were sent — a form of voter suppression that's uniquely a consequence of the reeling economy.

And, like most forms of disenfranchisement, this fall's potential for a mass eviction crisis is expected to affect minority communities the most.

"Even before Covid-19, evictions disproportionately occurred in communities of color," said Eric Dunn, director of litigation at the National Housing Law Project, a nonprofit that aims to improve housing and bolster tenants' rights in poor communities. "Black women face more evictions than anyone else."

While estimates vary on precisely how many could lose their homes before Election Day, the Trump administration's own numbers paint a grim picture. A Census Bureau survey in July found 9.9 million renters have "no confidence" they can make their next monthly payment — the people likeliest to be kicked out of their apartments or homes by November. And three out of every eight of them reported other adults and potential voters were living with them. (To be sure, some are not citizens, have felony records or otherwise may not be allowed to vote.)

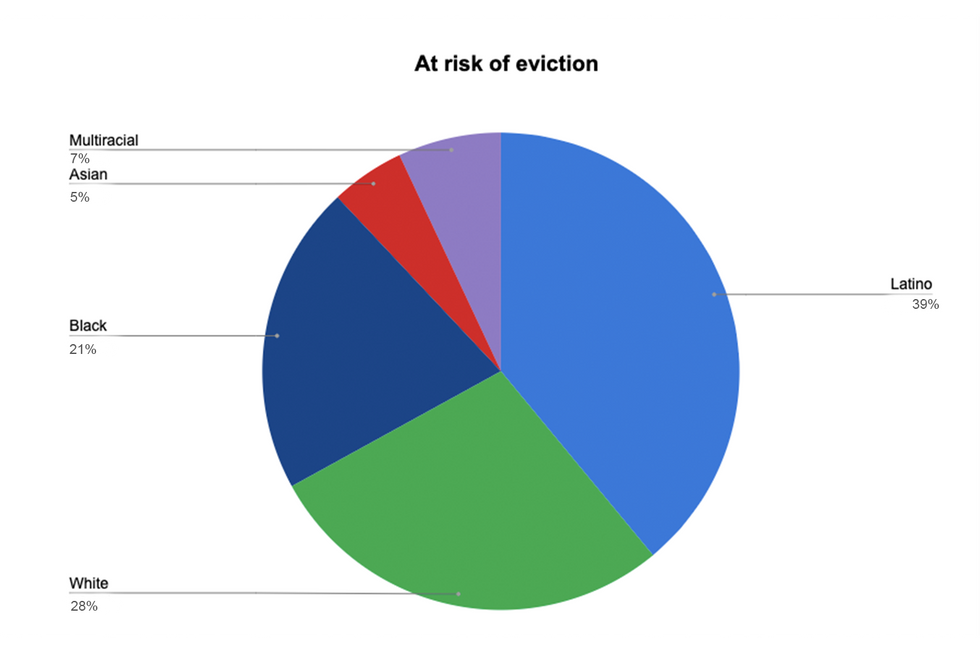

People of color account for 72 percent of tenants who said in July they have "no confidence" they can pay their next rent check. Source: Census Bureau

People of color account for 72 percent of tenants who said in July they have "no confidence" they can pay their next rent check. Source: Census Bureau

In addition, 72 percent of the people signaling they can't pay the rent identified as non-white. In an election that could see very different results based on turnout by Blacks and Latinos, a wave of displacement for voters of color could be a big problem for Democrats — who are counting on sizable blocs of minority votes, especially in big cities, to help them carry presidential swings states and win tight Senate contests.

In battleground Wisconsin, for example, which President Trump carried by less than 1 point in 2016, research afterward found that Black turnout had plummeted from four years before. Any reversal in 2020 won't be helped by the situation in Milwaukee, the state's largest city, where eviction filings are higher than this time last year. The spike is especially prevalent in majority-Black neighborhoods, according to Eviction Lab, a nationwide eviction database.

Tough to get a ballot without an address

Even for evicted people who find refuge quickly, many won't have access to voting by mail. Absentee ballots that can't be received at the address where the voter was registered are returned to the state.

"Ballots typically cannot be forwarded if the intended recipient's address is out of date or if the mailpiece is not properly addressed," the Postal Service explained in a statement, a policy that predates this year's reductions of services that have Democrats questioning if USPS is working to sabotage the vote. "Accurate and updated addresses are necessary to help ensure the timely delivery of election mail."

While other mail can be sent along to a new address, absentee ballots cannot be forwarded — a longstanding guard against the sort of voter fraud the president falsely claims is widespread.

That means that, even if voters find a new place to live in their old neighborhood, they won't get mail ballots if they've left their previous address and do not update their registration. The deadline in 26 states is three weeks or more before Election Day.

"You could potentially see an election where millions of people who have registered to vote using their address no longer live at those addresses," says Zach Neumann, executive director of the Covid-19 Eviction Defense Project, a nonprofit created this spring to combat homelessness during pandemic. "And as a result, they don't know where to go to vote if they're voting in person or aren't there to receive their ballots if they're in a state that ultimately opts to provide a vote-by-mail option."

People most at risk of eviction are also among those who live in communities with the highest rates of coronavirus infection — highlighting again that voters will be confronted this fall with the choice to either exercise their right to vote or to keep themselves away from a potentially fatal illness.

Waves of the newly evicted showing up at polling places, for no reason except that's their only option, could compound the sorts of problems that plagued primaries in Georgia, Wisconsin and other states this year — topped by hours-long waiting times, exacerbated by a severe shortage of poll workers and in many places fewer polling places.

Because elections are administered by states, there will be ample variance in how difficult it will be for people recently forced out of their homes to cast a ballot.

Colorado, for example, has been conducting its election almost entirely by mail since 2013 and is prepared for issues displaced people will face. As long as voters update their addresses a week before the election, they can still get their mail ballot. If they don't, Colorado's same-day registration option and voting centers make it possible to show up and have a good chance of being able to cast a ballot.

"You can get up in the morning, go to your computer, register to vote online and then go show up. And by the time you get to the in-person voting place, they've already processed your registration," says Amber McReynolds, CEO of the nonpartisan National Vote at Home Institute. "It's continuous. They're continually updating addresses, accepting registrations, all of that, through Election Day."

But not all voting systems are created equal, and the more strict election laws make it harder for displaced people to vote.

In Mississippi, for example, a collision of voter identification laws and residency requirements could prove a problem. The state says people must be residents of the county where they vote for 30 days beforehand, so anyone moving across county lines would be disenfranchised. The same would go for voters without the right address on a driver's license, by far the most common form of photo ID the state requires.

No matter what state a voter ends up in, though, they will have the option of casting a provisional ballot if they don't qualify to cast a regular ballot on Election Day. Such a ballot allows voters whose eligibility is in question to still vote — but the ballot isn't tabulated unless eligibility is later confirmed.

Federal law has required all states to have a provisional ballot system for almost two decades. The challenges, their critics say, is that they take longer to verify and count, so a spike in their use in November could delay the final results even more than the guaranteed surge of mailed ballots.

What about Trump's executive order?

Trump signed an executive order this month telling federal agencies to do what they could — which may not be much — "to ensure renters and homeowners can stay in their homes."

He acted after talks broke down in Congress over the latest coronavirus relief package, saying his directive was a way of "protecting people from eviction" after the expiration of a federal moratorium on the practice, which was included in the economic relief package enacted in March.

That moratorium protected anyone who rented a property that had a federally backed mortgage or tenants who received government-assisted housing, which was about a third of renters across the country. Now, unless those people live in states that have their own eviction moratoriums, millions could be facing eviction before the election.

The new order gives the Department of Housing and Urban Development authority to "take action, as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, to promote the ability of renters and homeowners to avoid eviction or foreclosure resulting from financial hardships caused by Covid-19." The department can also find "any and all available funds" to give renters and homeowners temporary financial relief.

But experts say that isn't helpful for people whose overdue rent is closing in on them.

"Trump's executive order does nothing to help the 30 to 40 million people who could become homeless by the end of the year and in fact creates confusion for renters and homeowners alike," Deborah Thrope of the National Housing Law Project said in a statement. "The order outrageously asks HUD to look under the couch cushions to solve a massive housing crisis."

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift