Solomon is the senior digital strategist at Next Level Studios, a legal marketing firm, and an adjunct management professor at McGill University in Montreal.

It's been less than two weeks since the election outcome became clear, and there are still almost nine weeks to the inauguration. But already it seems almost certain that the transition between Donald Trump's administration and Joe Biden's administration will come to be viewed by both historians and the public as among the worst transitions in American presidential history.

But it does not stand alone. There have been several other presidential transitions throughout history that have been rocky for different reasons.

The transition from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan 40 years ago was a difficult one because of the global political situation at the time. While it is true the two were as different personally and ideologically as presidents can probably ever be, the most significant obstacle to their smooth transfer of power was the situation on the ground in Iran.

In the weeks after his resounding defeat by Reagan, Carter was reported to have worked many 20-hour days in hopes of freeing the American hostages being held in Tehran. The welcome result of his work was not evident until the day Reagan took office in January 1981, leaving both a happy and sad historical footnote for the nation — and solidifying an inaccurately uncharitable legacy of the Carter presidency.

Some presidential transitions have been extremely difficult because of the personal relationship between the outgoing and incoming presidents. That was certainly the case when Dwight Eisenhower was elected after almost eight full years of Harry Truman.

Their rift grew from perceived betrayals of the foundation of a strong cooperative working relationship that was never much of a friendship. At one point, Truman was considering promoting Eisenhower to be his successor as the Democratic nominee in 1952.

Obviously that didn't work out, as Eisenhower chose to run as a Republican. The subsequent transition was marred by a complete lack of civility between the two, which included Eisenhower refusing to attend a holiday lunch at the White House and refusing to meet Truman before the inauguration ceremony, another break with tradition.

It is impossible to have a discussion about the worst presidential transitions without mentioning the historical one-day switch from Richard Nixon to Gerald Ford. The overnight timing was reminiscent of some of the darkest moments in American history, the four times a president has been assassinated. But rather than the nation dealing with the actual death of one president while his successor takes command, the people watched in August 1974 as the Nixon presidency was euthanized in real time.

While history looks through a glass darkly at the brief Ford presidency, it is important to remember he had been vice president for only eight months before he was given only a few hours (after Nixon revealed his resignation decision) to prepare to assume the Oval Office. Even the most capable and savvy of politicians, which Ford was not, would have found this transition difficult to bear. Charged with the ominous responsibility of leading a nation in a perilous place after Watergate, this difficult transition did nothing to help Ford get off on the right foot.

But to find what many historians believe to be the worst transition in presidential history, we have to go back to the ascension of Abraham Lincoln.

While we talk a lot today about how the United States has become a nation divided, in 1861 that was literally true: Seven of the 33 states — South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas — succeeded from the union between the day Lincoln was elected and the day he took office.

What made the transition even more tenuous was the result itself. Lincoln had garnered just 40 percent of the popular vote, still the second-smallest winning share in presidential history. (John Quincy Adams won in 1824 with 31 percent.)

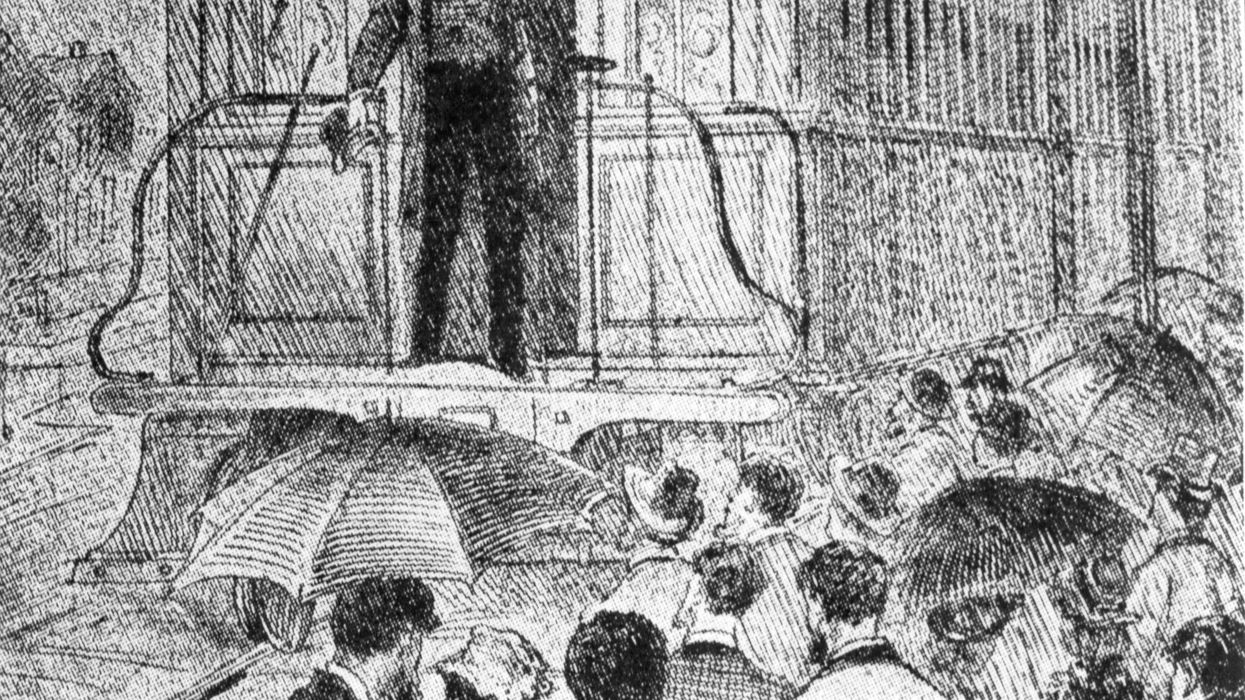

As history reminds us, what propelled Lincoln from arguably one of the worst changeovers into one of the best starts to a presidential term was the way the transition ended — with his legendary 13-day, seven-state, 1,600-mile train trip from his home in Springfield, Ill. The whistle-stop tour allowed him to change American public opinion by bringing out massive crowds in nine of the nation's biggest cities. By the time he arrived in Washington, the legend and myth that we recognize as Abraham Lincoln today had begun to form.

The days after a presidential election are way too early a time to predict the legacy of the next president. Yet history has shown that while many difficult transitions have led to similarly strained tones throughout an entire term, it is also possible to transform a difficult transition into a successful presidency.