Klug served in the House of Representatives from 1991 to 1999. He hosts the political podcast “ Lost in the Middle: America’s Political Orphans.”

All of us have had that moment. An innocent comment over coffee with a friend, at a family dinner or while riding an elevator with a coworker. Everyone is at edge over politics. Nerves are rubbed raw. Civility has seemingly vanished.

When asked to rate the level of political division in the country on a scale of 0-100, where 0 is no division and 100 is the edge of a civil war, the mean response is 71, according to the Georgetown University Institute of Public Service. A similar share of Americans tell Pew they worry about political disagreements triggering more violence.

Little noticed on this side of the Atlantic is the reality of what can happen.

In recent years, two members of the British Parliament were killed while on the job. In the fall of 2021 Sir David Armess walked to his office in Leigh-on-Sea, a city of 22,000 in Essex, on the southeast coast of England. Waiting for him was a constituent, Ali Harbi Ali, upset with Middle Eastern politics. Minutes later, the member of Parliament was dead after getting stabbed more than 20 times.

Five years earlier, another member of Parliament, Jo Cox, was murdered on her way to a similar meeting. This time by a right-wing fanatic.

“It used to be the tradition where you could walk up to a member of Parliament and have a chat. Now you would be mental to allow that to happen,” Sir Eric Pickles of the House of Lords told me. “You now want to know who the person is. You want to have an agreed exit plan with your staff, and all that kind of thing.”

After those two tragedies, several British foundations gathered to try to cool the nation’s political temperature. They knew they couldn’t change the zeitgeist overnight, but they could single out leaders as role models who were trying to depolarize rhetoric and drive consensus politics.

“We had quite modest expectations about the effect it would have on behavior change and part of it was just symbolic,” said Ali Goldsworthy, who helped spearhead the creation of the National Civility Award in Politics. “We wanted to honor people who have reached across divides in a very polarized time in the U.K.”

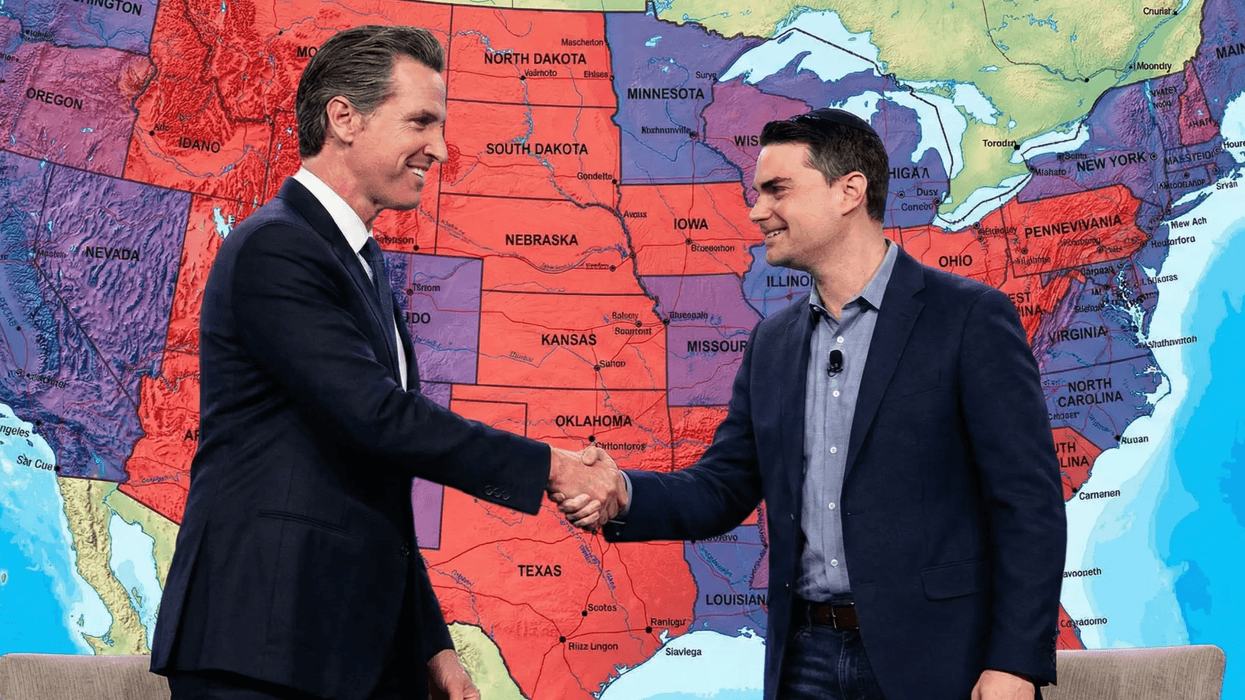

You would be hard-pressed to find a more divisive issue in the U.S. than abortion. But the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union, colloquially known as Brexit, was even more polarizing.

In the end, however, one of the parliamentary leaders of the pro-Brexit movement, Steve Baker, was chosen for the award because of the message he delivered the night his side won.

“I very much regret the division this country has faced,” Baker said. “I very much regret the sorrow of my opponents will feel. I look forward to working with them tomorrow.”

When was the last time you heard an American politician assume that tone?

Now in its third year, the British Civility Award singles out political leaders across the political spectrum. Perhaps we should adopt the idea.

And we have stories of more people trying to change the current political zeitgeist in our “Lost in the Middle” podcast episode “Maybe America needs a mom to call a time-out.”

Maybe America needs a mom to call a big time-out by Scott Klug

Read on Substack

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift