Clements is the president of American Promise, a nonprofit advocate for amending the Constitution to allow more federal and state regulation of money in politics.

On Jan. 21, 2010, the Supreme Court decided Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, striking down key provisions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. The court decided that corporations and unions (and, by implication, anyone who can afford it) have a free speech right to spend unlimited money to influence American elections. In practical terms, Citizens United enabled billionaires, corporations, unions, even foreign government interests, to funnel money through super PACs and other entities that dictate how American elections are financed, how candidates are selected and what information voters receive.

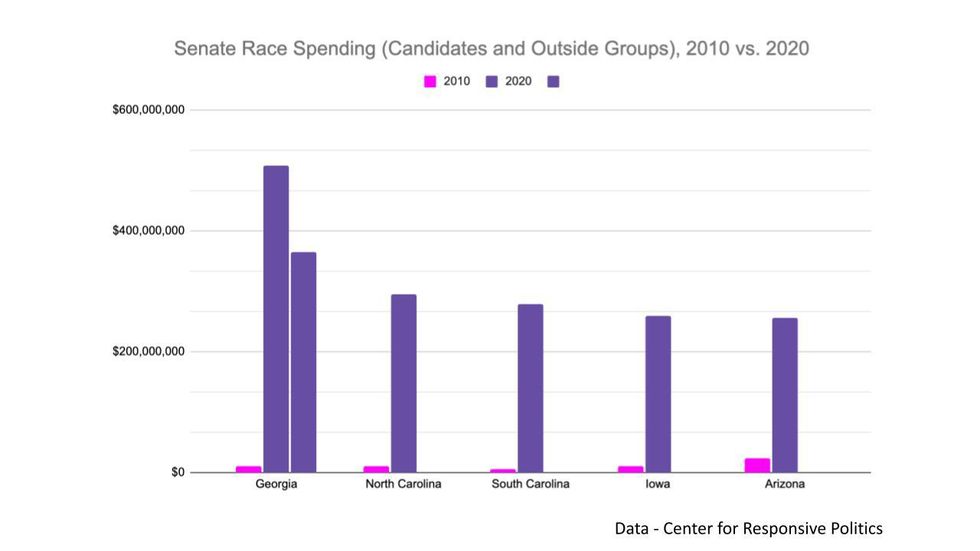

Today, 12 years later, election spending is overwhelmingly sourced from an unrepresentative elite “ donor class.” Nearly half of the super PAC money in the past decade came from just 25 billionaires. We’ve had a $15 billion federal election, U.S. Senate races with $200 million to $500 million in spending, and a vitriolic presidential election leading to riotous violence in the halls of Congress itself. The magnitude and velocity of the money in elections is reflected in comparing the top Senate races in the 2020 elections with the most expensive Senate races in 2010.

Source: Open Secrets

Source: Open Secrets

Most of the billions go to negative, divisive, ill-informative targeted messages, intended to either boost partisan turnout through fear and rage, or depress turnout among opponents’ supporters through cynical attacks and misleading information. Democrats and Republicans both use these same dark money techniques. As one member of Congress recently told me, “There is no way we will ever work together or be able to get anything done when we are spending billions of dollars to demonize and tear each other apart.”

Citizens United is now on the list of the most famous or infamous Supreme Court decisions, which also includes Dred Scott, Brown v. Board of Education, Plessy v. Ferguson, Roe v. Wade, Korematsu, Gideon v. Wainwright and the like. These decisions were all flashpoints, fulcrums of history, moments in time when constitutional interpretation and decision-making burst out of the courtrooms and the lawyers’ offices and into the public square, kitchen tables and conversations of most Americans.

Before Citizens United, most Americans had not joined the legal debate about the interplay of the First Amendment, election money and corruption. But for decades they had experienced first-hand how both major parties had become dependent on a donor class who can move billions of dollars into campaigns. They had seen how government had repeatedly failed them but always seemed to answer the call of those with money.

The court can wishfully proclaim, as it did, that the obvious unfair access and influence of the big donors “will not cause the electorate to lose faith in our democracy.” But it’s too late: By 2016, fully 92 percent of Americans believed government was run “for the benefit of a few big interests ” rather than the common good. As a Kentucky citizen explained to the Our Common Purpose Commission from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, “you have to believe that you have the opportunity to elect the people you need speaking for you. You have to trust them and they have to trust you. And I think that’s really broken right now.”

For many, “Citizens United” is shorthand to describe how Americans lost our freedom to protect our families, communities and states from corruption, and to protect our right to speak and participate on equal terms as citizens in effective representative government. Most Americans across the partisan spectrum oppose the decision and support a constitutional amendment to fix the problem with effective regulation of money in state and federal elections.

Twenty-two states so far have backed this Constitutional amendment. (You can see more on the amendment wording and weigh in with your views at American Promise). This follows a pattern in American history: Eight of our 27 constitutional amendments were in reaction to Supreme Court decisions that were viewed as dangerously out of step with the views and lives of the country at large. In these “constitutional moments,” the status quo no longer works or is acceptable. And a Supreme Court decision that reinforces that status quo triggers rather than resolves a constitutional debate.

In Citizens United, the court expanded a First Amendment theory that most Americans have long rejected: that increasing the influence of an aristocratic money class would bring more freedom, speech, ideas and uncorrupted, competitive elections. Americans always reject this theory, from the American Revolution and the fight against oligarchic “Slave Power” to the successful constitutional amendments and laws that curbed the power of Gilded Age plutocrats and the post-Watergate reforms and grassroots movement that forced Republicans and Democrats to pass the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act in 2002.

That fight of freedom versus aristocracy is what is at stake now, and the issue is no longer about “overturning” Citizens United. It is about whether we will act to right the ship before it’s too late. It is about how we rescue free speech and the First Amendment for all Americans.

No one remembers “Overturn Minor v Happersett!” But we remember the 19th Amendment and the simple justice of “Votes for Women.” Few but the lawyers know of Chisholm v. Georgia, but we all live in a republic that reflects the 11th Amendment and the fierce response to the Supreme Court’s overreach to protect creditors and federal power at the expense of the states.

So as before, we can leave the specific Supreme Court decisions that got us into this mess behind and move forward to resolve for ourselves, as a nation, this great constitutional question about power, equal opportunity and freedom. We can do this not with abstract theory but with the undeniable facts about the unjust and dangerous way money is power in our politics today.

Who has a right of free speech — everyone or just a few big donors and spenders? Can we control our own destinies, our communities, our unique and various state interests by curbing the rapid transformation of every election, from the Senate to school committee, into fights between national donor factions?

With a constitutional amendment, we can answer these questions soundly. And when we do, we can end foreign government interference in our elections; each state could decide for itself how to protect its voters and interests from domination by outside billionaires or global corporations; businesspeople could be freed from extortionate demands by the politicians and parties who can make or break them; we could end super PACs, open up competition with more voices and views, and make election spending transparent; we would check the power of incumbency and the stranglehold on power possessed by aged “leaders” who control the money flow, enabling more real debate, compromise and problem-solving.

There is no single answer to the age-old problem of money, corruption, election integrity and an equal say at the ballot box. Instead, as with all good constitutional law, an amendment enables, but doesn’t dictate, better possible outcomes.

After a dozen years of billions of dollars, systemic corruption, and an angry, dispirited, divided and alienated electorate, we know where bad constitutional interpretation takes us. But as always in America, the Supreme Court does not have the last word; it has opened, rather than ended, a great constitutional question. Now it is up to all of us to resolve it.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift