Williams is an assistant Professor of Political Science, Allegheny College. Bloeser is an associate professor of political science and director of Center for Political Participation at Allegheny College.

When Joe Biden was the Democrats’ candidate for president in 2020 and again in 2024, he staked his candidacy on being the person who would save democracy from the threat Donald Trump posed.

But Kamala Harris has shifted away from that message and toward the idea of protecting and advancing freedom. Freedom has become the theme of many Harris campaign ads and speeches. Her slogan “ we are not going back ” is meant to invoke concern about freedoms being taken away.

As scholars of citizens’ commitment to democracy, we see a few reasons that promoting freedom might be a more effective campaign message than protecting democracy. One is that our research and others’ has found that a lot of Americans aren’t very concerned with democracy.

Wide support for violating democratic principles

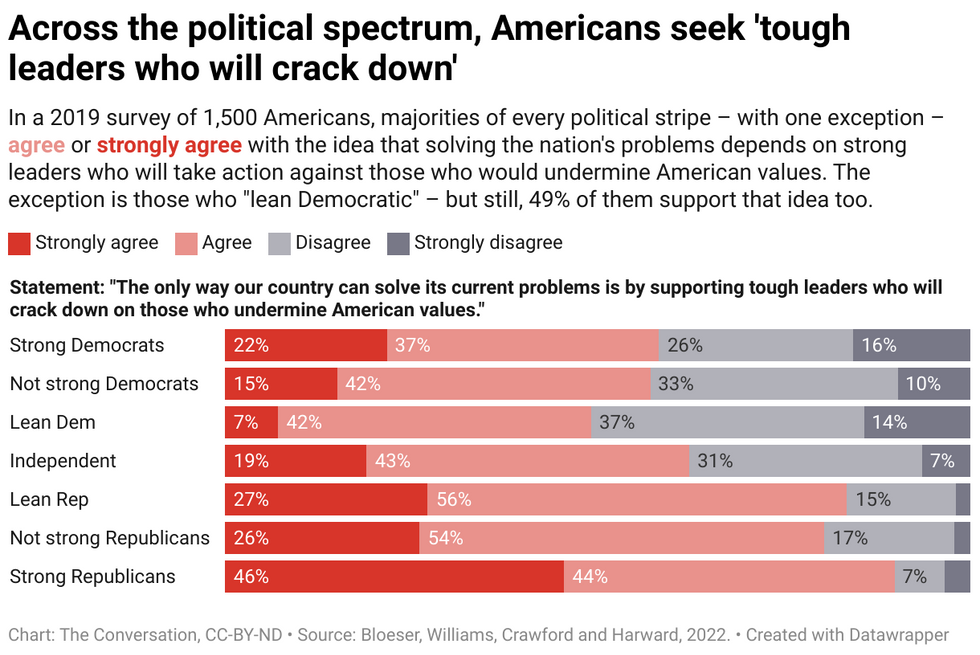

In our research, we have found that when people think about groups that threaten their values, they are willing to support political representatives who offer protection against the perceived threat. Using a nationally representative sample of 1,500 respondents from 2019, we found that a large proportion of Americans are willing to support leaders who would violate democratic principles such as freedom of speech and following collectively agreed-upon rules and laws.

Majorities of Americans, across the political spectrum, indicate that they want leaders who will “crack down” on groups they find threatening. Many also indicate that they would support leaders who would “bend the rules” to “protect the interests of people like you.” Notably, however, people who identified as Republican supporters were the most likely to want leaders who will take these sorts of actions.

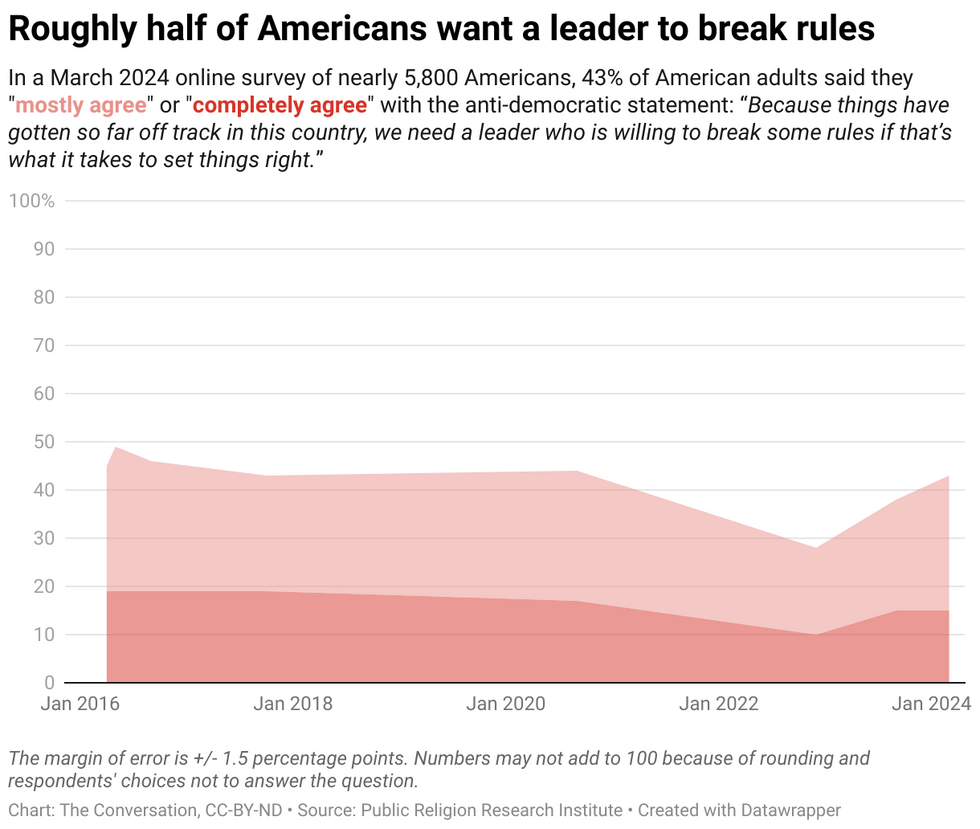

A March 2024 survey from the Public Religion Research Institute asked a similar question and found that more than 40% of Americans agree with this statement: “Because things have gotten so far off track in this country, we need a leader who is willing to break some rules if that’s what it takes to set things right.” Strikingly, half of Republicans endorse this statement.

Perhaps surprisingly, messages that highlight threats to democracy do not seem to be effective. Recent political science research finds that negative messages emphasizing the threat Trump poses to democracy are less effective than positive messages about what Harris will do.

Other scholarship suggests sparking fear makes people think, but it does not spur them to action. Enthusiasm, however, can move people to participate. The question is what might lead people to feel enthusiastic.

Is freedom the answer?

Over the past several decades, America’s two major parties have taken different approaches to mobilizing their supporters to vote. Republicans have been successfully messaging on symbolic values and ideology, often talking about abstract values such as freedom. Democratic candidates, meanwhile, have focused on policy messages that help them appeal to coalitions of diverse social groups.

For example, as Congress debated what would become the Affordable Care Act, Republican opponents criticized the legislation for stripping freedom away from citizens and raised concerns about government overreach. These efforts provided a theme that led many Republicans to victory in the 2010 congressional election. At the time, Democrats emphasized the benefits to particular groups, such as young people, women and lower-income Americans, rather than emphasizing an overarching ideological cause. Over time, they have taken a similar tack on issues pertaining to the rights of workers, women, the LGBTQ community and racial minorities.

The Harris campaign appears to be changing the Democrats’ approach. For instance, she has cast restrictive abortion policy as an instance in which the government infringed upon the personal freedom of citizens.

Similarly, Harris has focused on protecting the rights and freedoms of people of color and LGBTQ Americans.

Harris’ unning mate, Tim Walz, echoed this messaging at the Democratic National Convention. He told the crowd, “No matter who you are, Kamala Harris is gonna stand up and fight for your freedom to live the life you want to lead. Because that’s what we want for ourselves. And that’s what we want for our neighbors.”

Will it work?

The effectiveness of this turn toward freedom remains to be seen. Yet there is reason to believe that this messaging can influence voters and have larger benefits for American society.

Freedom is a core American value. But for much of this century, freedom has mainly been defined by the Republican Party, as the absence of government interference in one’s life. This notion of freedom provided a basis for policies such as lower taxes, less government regulation and fewer social services.

The Harris campaign has begun to offer a rival vision of freedom, even if it is not quite fully formed. Her idea most resembles the notion of freedom that some political theorists call “ freedom from domination.” This concept implies that citizens should live under societal conditions that prevent some individuals or groups from having unjustified control over others.

Importantly, to accomplish this, freedom from domination implies that government policies can be useful for creating conditions that enable increased freedom. If people struggle to afford child care, health care or education, social policies that alleviate that struggle can help people achieve greater autonomy to make choices that affect their own lives.

Regardless of which conception of freedom a person prefers, or which party they generally support, the Harris campaign’s decision to talk about freedom is consequential. It opens the door to competition between parties over how to think about a core American value and pushes political discussions away from the politics of retribution.

It isn’t always obvious how to counter threats to democracy, but Harris’ positive message around freedom offers one possible strategy. If Harris wins in November, it may indicate that focusing on a shared value such as freedom could be a more effective way to combat the threat to democracy, rather than focusing voters’ attention on the threat itself.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A woman prepares to cast her vote on May 4, 2025 in Bucharest, Romania. The first round of voting begins in the re-run of Romania's presidential election after six months since the original ballot was cancelled due to evidence of Russian influence on the outcome. Then far-right candidate Calin Georgescu surged from less than 5% days before the vote to finish first on 23% despite declaring zero campaign spending. He was subsequently banned from standing in the re-rerun, replaced this time round by George Simion who claims to be a natural ally of Donald Trump.Getty Images, Andrei Pungovschi

A woman prepares to cast her vote on May 4, 2025 in Bucharest, Romania. The first round of voting begins in the re-run of Romania's presidential election after six months since the original ballot was cancelled due to evidence of Russian influence on the outcome. Then far-right candidate Calin Georgescu surged from less than 5% days before the vote to finish first on 23% despite declaring zero campaign spending. He was subsequently banned from standing in the re-rerun, replaced this time round by George Simion who claims to be a natural ally of Donald Trump.Getty Images, Andrei Pungovschi

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift