States are taking steps to protect their voting systems from the sort of cyberattacks that marked the 2016 presidential election, but they lack the funds to do all that's needed.

That is the conclusion of a report released Thursday by four groups that monitor voting security or advocate for additional federal intervention to bolster cybersecurity for the political system: the Brennan Center for Justice, R Street Institute, Alliance for Securing Democracy and the University of Pittsburgh.

They sampled what is happening in six states, chosen in part because hacking was attempted in several of them in the past few years. In Illinois, for example, special counsel Robert Mueller's report found that Russian operatives hacked into the state database of registered voters and extracted some data before they were blocked.

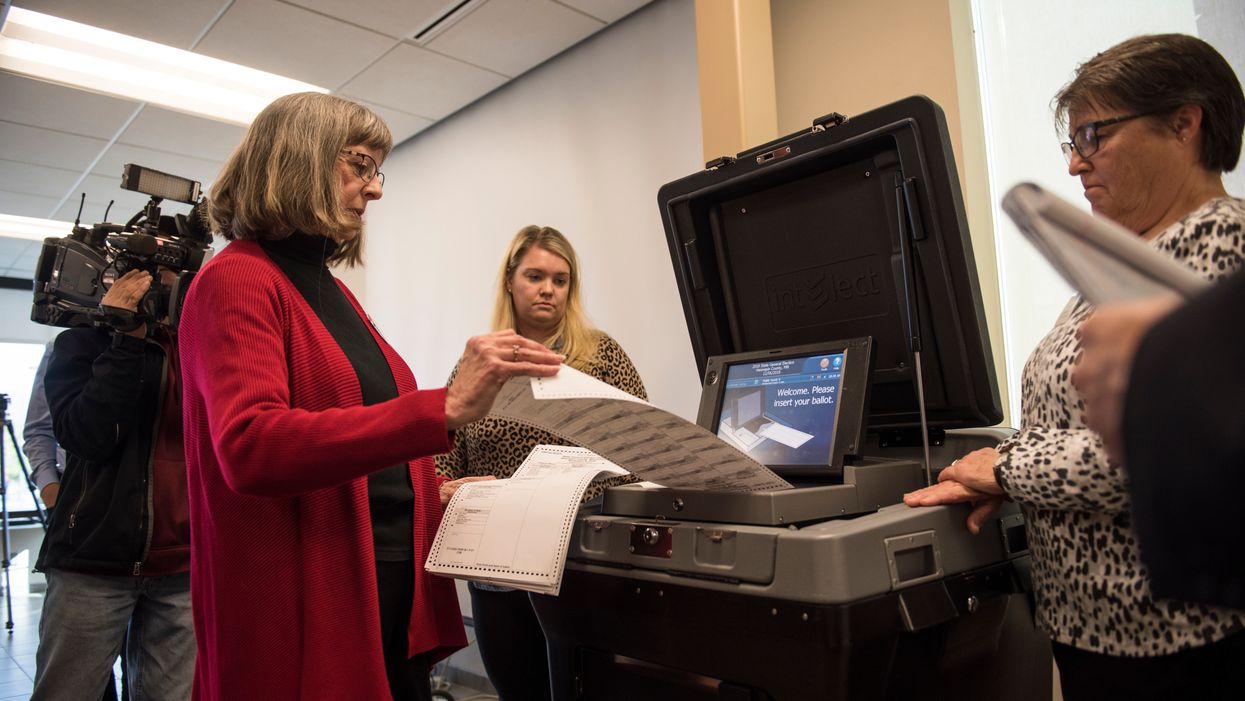

One common theme among the states is their hunger for more federal aid to replace aging voting machines.

As the report points out, the states all tapped into the $380 million approved by Congress last year for election security grants to the states — but could have used far more. The House has voted to allocate another $600 million for security grants before November 2020, but the Senate has not yet begun to write the spending bill that might contain similar funding. The delay is knotted up in a much larger debate about the overall size of the federal budget for the coming year.

Here is a look at what has happened so far in the states that were studied:

- Alabama: Using a $6.2 million grant to upgrade its voter registration database, replace computer equipment used by county election officials and conduct post-election audits. Now it needs to replace aging voting equipment and to create a cyber-navigator program to provide expert help to local election officials.

- Arizona: Using $7.5 million to replace its voter registration database, conduct a security assessment and establish information sharing with local officials. Now it needs to replace an old voting system and create a cyber-navigator program.

- Illinois: Using $13.2 million to fund a cyber-navigator program. Now it needs to replace old voting systems, estimated to cost $175 million.

- Louisiana: Using $5.9 million to replace paperless voting machines. The state needs more to finish the job.

- Oklahoma: Using $5.5 million to upgrade its voter registration database, conduct training with local election officials and purchase electronic poll books. Now it needs to replace voting equipment and upgrade software allowing post-election audits.

- Pennsylvania: Using $13.5 million to replace paperless voting machines. Now it needs $135 million more to finish that task, plus money to replace its voter registration system.