Redistricting reformers in Nevada have another shot at getting their initiative on the November ballot after a federal judge allowed for more time to collect signatures.

Judge Miranda Du of Reno has given Fair Maps Nevada six extra weeks to circulate petitions but turned down the group's request to be allowed to collect electronic signatures. Adhering to this month's deadline in light of the coronavirus pandemic would be unconstitutional, she wrote Friday, but relaxing the state's requirement for handwritten signatures could incubate fraud.

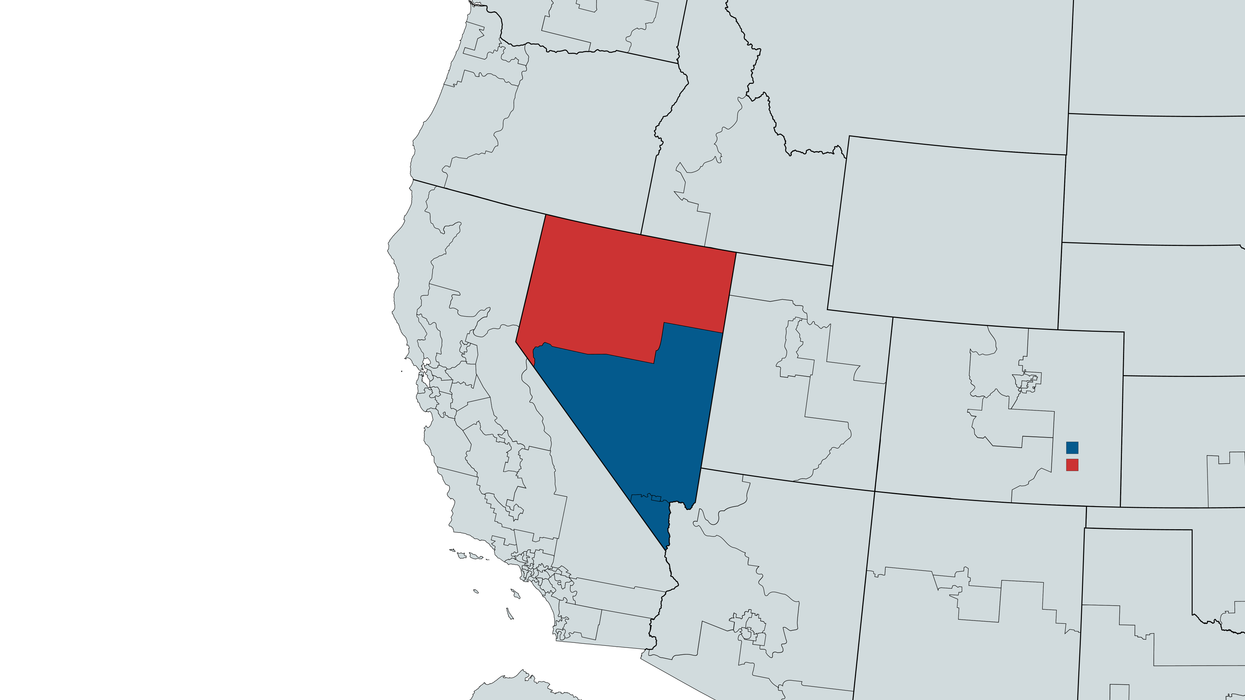

Approval of the ballot measure would create a nonpartisan commission to replace the Legislature in drawing both the congressional and state legislative maps for the state, which is now the case in eight other states.

The November election is the last shot at redistricting reform for a decade, because new maps are drawn nationwide once the census provides detailed population counts.

Originally, Fair Maps Nevada had until June 24 to collect at least 98,000 signatures — and said it had gathered only 10,000 when Democratic Gov. Steve Sisolak imposed a statewide stay-at-home order in April. He has since reopened most businesses but continues to encourage people to remain out of public places if possible.

Since the group could not collect signatures due to Covid-19, the judge wrote, "it is both unreasonable and unfair not to extend a statutory deadline for a corresponding period of time."

The new deadline is Aug. 5, or 90 days before Election Day. Du said the group and state officials could agree on a different date, but she recommended "an extension corresponding to the precise length of time the stay-at-home order was in effect."

Allowing e-signatures would make the citizen's democracy effort more susceptible to fraud and require the court "to get impermissibly in the weeds of designing election procedures," Du wrote, noting the Supreme Court precedent that strongly discourages lower federal courts from altering election rules.

A similar referendum is already on the ballot in Virginia and proponents for such a measure in Arkansas are also asking the courts for more time to get signatures. Missourians, on the other hand, will vote in November on whether to reverse a redistricting reform initiative approved two years ago.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift