Penrose is the lead author of “ Our Shared Republic: The Case for Proportional Representation in the U.S. House of Representatives.” Daley is the author of “ Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count ” and “ Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy.”

Our country is more politically sorted than it has been in a century, but we are not nearly as sorted as the simple narrative suggests. Liberal voters live in the reddest parts of rural America, and conservative voters live in the bluest of cities. However, they are invisible in winner-take-all congressional elections. Every vote they cast fails to elect anyone.

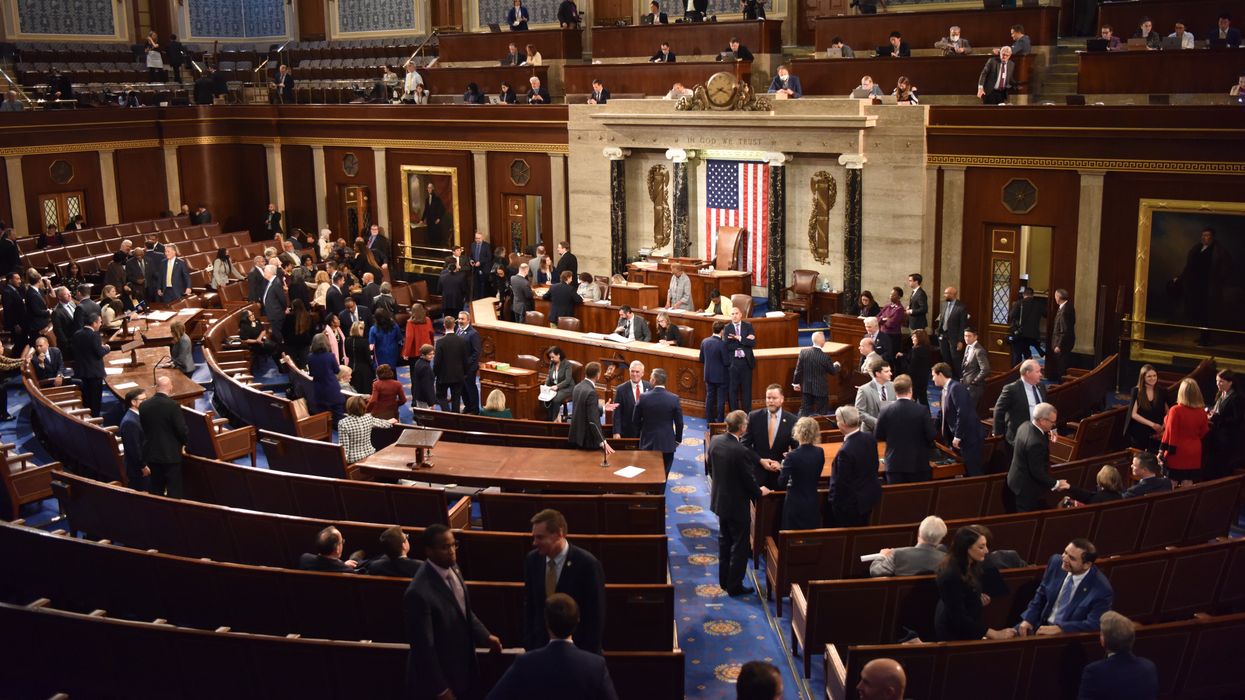

That means they’re invisible in Congress itself, which John Adams wrote “should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people.” Instead, the people’s House is the very picture of gridlock and extremism. It’s an unrepresentative body sent to Washington from uncompetitive districts in hyper-polarized times that has hamstrung action even on issues where large majorities of us agree.

While our politics may seem intractably broken, there are solutions available, if we can muster the will to change. Much of the national reform energy revolves around ending gerrymandering or opening primaries, but while both of those fixes would do some good around the margins in a handful of states, genuinely solving the problem everywhere requires a bolder approach.

The most meaningful change would put an end to winner-take-all, single-member districts and create a proportional House with larger, multimember districts and proportional voting. This might sound like a big lift, but it’s fully constitutional, deeply aligned with our founding vision, and only requires Congress to pass a statute. For example, the Fair Representation Act, a bill to be reintroduced in Congress this week by Reps. Don Beyer (D-Va.) and Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), would do just that by requiring every state to replace its winner-take-all elections with proportional ranked-choice voting.

The advantages of a proportional system would be dramatic and immediate. It would make every contest competitive in every state. It would end gerrymandering and more fully represent the breadth of ideas held by voters. It would greatly expand opportunities for communities of color to build power. And it would create incentives for legislators to work productively in service of the public interest rather than to obstruct and demean their opponents.

Single-member, winner-take-all robs us of the diversity of ideas and interests that exist across all regions of the country. Massachusetts, for example, is a blue state. In 2020, all nine of its congressional districts were safely Democratic. Yet across those districts, 1.2 million people backed Donald Trump for president. Likewise, the band of states running up the center of the country, consisting of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas, elected a combined 14 representatives, 13 of whom were Republicans. Yet across those 13 Republican districts, 1.5 million people wanted Joe Biden to be president.

In every congressional election, around 90 percent of districts have no meaningful competition at all. Polarization of the two major parties has created a self-reinforcing cycle of distrust that has already resulted in one abortive insurrection. New England Republicans and heartland Democrats currently lack a voice – when we know from history that when elected, they’re the bridge-builders who bring coalitions together.

A simulation of the Fair Representation Act showed that proportional ranked-choice voting and multimember districts would yield the equivalent electoral power of 30 new majority-minority districts nationwide. Under this system, a far greater proportion of voters of color would have a representative who is responsive to their community, including nearly all Black voters in the Deep South and nearly all Latino voters in the Southwest.

Today’s winner-take-all methods allow representatives to win elections with only a very small coalition of support, wasting the votes of all others. Too often, the expressway to Congress from a gerrymandered district is to run to the extremes in a low-turnout primary. Consider the election of Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, whose safe Republican district is home to about 730,000 people. Yet Greene won both her primary and her primary runoff election with fewer than 44,000 supporters.

The coalition that elected her is tiny, and neither ideologically nor demographically representative of the district as a whole. Her track record as a representative reflects that; she favors incendiary and extreme rhetoric that excites a small, dedicated group of voters over building coalitions for effective governance that would help more people.

If a substantial number of voters in a district want to elect a bombastic populist, it is their right to vote for that candidate. Under proportional ranked-choice voting, however, such a candidate would have to win a competitive general election and demonstrate the support of a substantial constituency. Extremists can win some seats under proportional voting methods too, but the incentives change in a way that tends to moderate, productive government overall. There would be competition in the general election – and with far different incentives to appeal to everyone in November, rather than the fringes in a summer primary.

Proportional representation really means full representation: Nearly every voter (at least 83 percent in a five-member district, for example) can point to an elected representative whom they voted for and helped elect. The proportion of effective votes — those that actually elected someone — is far higher than under winner-take-all.

And with proportional ranked-choice voting, the number of voters who ranked a winner as one of their top choices will be even higher. Voters need not fear “wasting” their vote on a longshot candidate; their vote can simply count for a backup choice if their favorite doesn’t stand a chance.

The adoption of proportional ranked-choice voting in the U.S. House of Representatives would help to realize James Madison’s vision for the chamber: a government able to temper the violence of faction through the representation of a great diversity of interests. So that the republic will not be mine or yours, but ours, and not be ruled, but shared.

Why does the Trump family always get a pass?