Richie Terrell is executive director of RepresentWomen. Richie led FairVote for 31 years and now serves as a senior advisor.

In our first article in this two-part series, we wrote about how 2023 is a special year for both of us: It’s the 30th anniversary of our wedding, of FairVote moving into its own offices, of Lani Guinier bringing proportional voting into the national consciousness, and of New Zealand completing a remarkable reform journey from winner-take-all voting to proportional representation. Now we turn to sharing our thoughts about how to translate New Zealand’s remarkable reform triumph to the very different realities of the United States.

It’s timely. Our national electoral rules are limited in offering the choices voters want to see, fluidly reflecting who we are as a people and creating incentives for tackling problems together rather than seeing every issue as a political weapon to get an edge. Despite heroic reform efforts, gerrymandering runs rampant and voters are increasingly stuck in hyperpartisan camps that result in relatively slight partisan advantages for one major party in a district becoming a nearly insurmountable obstacle to two-party competition, let alone giving independents and minor parties any chance.

We are excited by new energy for proportional representation (PR) – with major media and organizations like Fix Our House, More Equitable Democracy, and Protect Democracy joining the groups we’ve long led (FairVote and RepresentWomen) in making the case for changing winner-take-all elections. A major new poll on PR from Protect Democracy shows the conditions are right for Americans to have our “New Zealand moment” in the coming decade.

Yet we also have concerns and will propose how we might prevent “election method schisms” and the resulting paralysis that our New Zealand allies so artfully avoided. Most advocates of different forms of PR share a common critique of how the current system is falling short, and on paper any number of moves to PR would improve our politics. But there’s a reform horse out front, and we think it’s right to be there – not to the exclusion of other proposals, but in recognition of the most likely pathway to national change.

It starts with moving toward what to us is eminently in reach by the end of the decade: ubiquitous statewide and local uses of ranked-choice voting (RCV) and robust uses of a proportional form of RCV across cities and some states – and possibly our north star national reform goal of the Fair Representation Act, which would establish proportional RCV for congressional elections. Nationally, FairVote supports this advocacy – with RCV now winning 27 straight times on the ballot, with seven of those wins advancing its proportional form as well. RepresentWomen is building strong support among women’s representation advocates for both RCV and proportional RCV backed with compelling data about women holding more than half of seats in cities with RCV.

This progress is grounded in how we and our colleagues at FairVote long ago decided to prioritize this approach after much thought and effort to advocate for forms of PR. In 1992, FairVote’s founding name was Citizens for Proportional Representation – with the acronym and motto of “CPR! Resuscitating American Democracy.” After starting our first “CPR!” locally in Olympia, Wash., in 1991, we had picked up stakes and traveled that fall to sleep on basement floors of allies for two months to help a campaign in Cincinnati to pass the proportional form of RCV – one that narrowly lost, but led to Cincinnati hosting the national CPR’s founding conference in June 1992.

Rob led FairVote until this fall, when he moved into a senior advisor role, and Cynthia served on its board from 1992 to 2020. During that time FairVote has done much more than focus on RCV. We regularly have highlighted a range of PR systems. We supported and lifted up cumulative voting, as used successfully to settle many voting rights cases and with real political impact in Illinois legislative elections from 1870 to 1980. We proposed New Zealand-style “mixed member PR” (MMP) for American audiences by promoting a “Districts Plus” system. At the start of our drive to bring PR to Congress starting in 2011, we promoted as one option a form of PR that uses party lists, known as the “Free Vote system.”

But over time we became more focused on the proportional form of RCV. Last year, Rob wrote about his personal journey from being an early champion of bringing MMP to the United States to seeing the PRCV as the way to achieve proportional representation in the United States. Based on our own experience and the validation of events like FairVote’s 2015 “Democracy Slam” and a major scholarly exercise that year resulting in proportional RCV earning first place in impact on a rating of 37 structural reform, we’ve decided to prioritize winning RCV for all elections and PRCV for legislative elections when there are multi-winner districts electing more than one person.

FairVote’s resources on proportional RCV make our case for it, as does a powerful full page editorial in The New York Times in support of the Fair Representation Act and David Brooks’ column “ One Reform to Save America.” Rob’s New York Times piece in favor of the first version of the Fair Representation Act in 2017, with then-National Review executive editor Reihan Salam, includes the point: “Who is locked out of representation? Moderates and conservatives in our biggest metro areas, and liberals in the heartland. They are the tens of millions of voters who defy stereotypes of left and right, and are perfectly positioned to bridge our seemingly unbridgeable political divides. Our political life is being poisoned by the absence of their voices.”

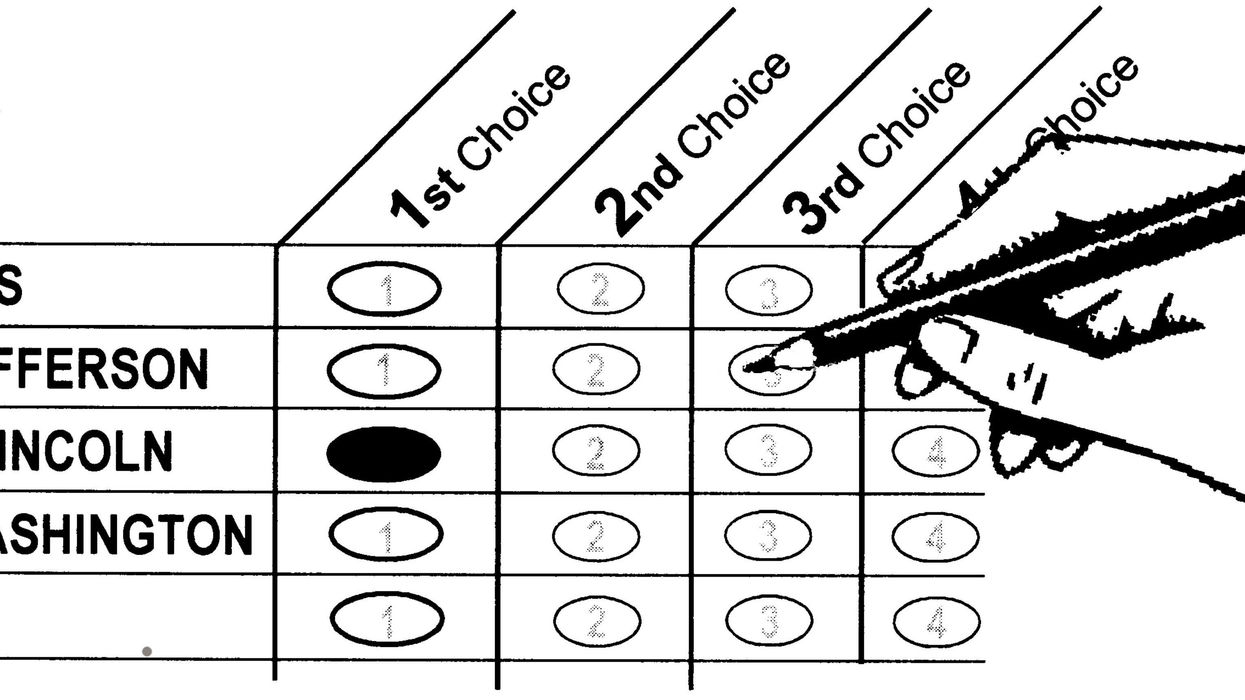

Even without its proportional form, RCV is powerful and sensible. Fundamentally, it makes your vote more powerful because your backup rankings act as an insurance policy if your first choice can’t win. The candidates know you have that power, and they will talk with more voters – and the ones who learn from and connect the best with voters are more likely to win. RCV improves a full range of elections, it’s winning legislatively and on the ballot, and it’s popular with voters. RepresentWomen has found women candidates embrace its incentives and hold more than half of seats in the cities using RCV.

Expect a lot more attention to RCV in the coming year. RCV is on the ballot to change statewide elections in Nevada and Oregon, and possibly several more. It will be used in several presidential primaries and gain ground in numerous state legislatures and cities. While the presidential election is sure to trigger much hand-wringing about several independent and minor-party candidates acting as “spoilers,” that won’t be the case in two states that have enacted RCV for their elections for president – Maine and Alaska. The other 48 states should follow suit with simple statutes to ensure more votes count, representative candidates win, and the “spoiler” debate is ended for good.

But here we want to focus on PRCV. PRCV is the best way to use RCV when electing more than one person in a legislature. It has passed in several American cities and will have a big first use in 2024 in Portland, Ore. The short narrative about why PRCV makes so much sense in the United States is tied to unique aspects of our system that were absent in New Zealand:

- RCV is the best way to elect candidates to executive offices in a multiparty democracy. Unlike many parliamentary democracies, we have numerous elected executive positions like president, governor and mayor, and RCV is the best way to elect such offices in a multiparty system. A multiparty democracy without RCV for president and governor either means far more controversial winners with low shares of the vote or runoff elections that are unwieldy and would effectively double the power of big money in our elections.

- PRCV is the only proportional system that works in nonpartisan local elections. Locally, the huge majority of city elections are nonpartisan. If we want to have a proportional system up and down the ballot, proportional RCV is the only way to go in most local elections.

- We need to accommodate independent voters and candidates. We have growing numbers of committed unaffiliated voters, including a substantial plurality of young voters getting registered, and independent candidates like Sens. Bernie Sanders and Angus King have been far more likely to break through and win as unaffiliated candidates than with a minor-party label. Party list backers need to come up with realistic ways to accommodate independent candidates and voters who don’t want to feel limited to what a party tells them should be their choices.

- Voting Rights Act jurisprudence is most consistent with PRCV. Proportional RCV is a powerful, proven and increasingly sensible means to enforce the Voting Rights Act when racial minorities experience vote dilution in winner-take-all elections. Party list systems don’t speak well to traditional voting rights jurisprudence – one that doesn’t focus on parties nor on descriptive representation, but is based on racial minorities having the power to elect candidates of choice.

- Turning back the clock on party control of nominations is a likely non-starter. Many of our state political parties are run by insiders who have not demonstrated a commitment to recruiting or supporting women, men of color, young people or party insurgents. Handing over the nomination process to party bosses is not likely to advance the reflective democracy many hunger for – and won’t be popular with voters who have grown deeply invested in having a role in choosing their party nominees.

- PR for Congress must accommodate small states. It would take a constitutional amendment to combine states when electing members of the House of Representatives. As a result, proportionality in outcomes is limited by how many seats are elected in each state. Today more than half of our states have small congressional delegations with fewer than seven seats. When six seats are elected statewide with a PR system it will take more than 16 percent of the vote to win – and in the 14 states with no more than three seats, the necessary share of the vote to win is more than 25 percent – a very high bar for minor parties. While House size could be increased by statute, any realistic change won’t do much to change this high threshold. As proposed in the Fair Representation Act, PRCV is the best way to enable real voter choice and fair representation in smaller states as well as larger states. Without an RCV ballot that gives voters an insurance vote if their first choice loses, party list systems would result in large numbers of wasted votes and “spoilers.”

- Individual legislators matter, and we don’t expect them to toe the party line. Unlike every other nation, our government systematically pays for primaries, putting voters in charge of defining their party nominees rather than parties. We also expect our elected leaders to have individual agency, with a history of far less party cohesion and control of floor votes and far more opportunities for individual legislative creativity in preparing legislation and offering amendments.

Even so, some new American advocates of PR are wary of proportional RCV because of their focus on strengthening political parties and increasing their numbers as tools to address polarization. While we agree with the value of parties, we also see limits. Americans aren’t ready for our elected representatives to act like those elected in party list systems that dominate Europe and Latin America – where party leaders negotiate governmental and legislative deals, and backbenchers do what they’re told and vote the party line on nearly all major issues.

To be sure, this approach to legislative behavior is common around the world and would have its intellectual attractions if we were starting from scratch. But we’re not – and philosophical debates are better suited for the classroom than for winning reform. Americans have deeply ingrained traditions of our system working best when “big tent parties” avoid the kind of single-minded factions that James Madison warned against – thereby giving parties the flexibility to run chambers with a mix of different perspectives within them and enabling shifting groups of representatives to pass legislation depending on its content and how it was developed in committees. Having major parties with internal “factions' 'would allow for different majorities on different issues in a manner that was central to the Madisonian vision of our governance. Rather than a problem, we see enabling legislators to think for themselves as deeply American.

We also unapologetically embrace the power that RCV gives to individual voters – that is, ensuring voters have the power to decide how to rank their second and additional backup choices, rather than have that power governed only by whichever party they support. We also don’t want to turn back the clock on the reality of the growing number of unaffiliated voters – particularly among young people – who don’t want to be forced to cast meaningful votes only through parties and will want to consider independent candidates. With PRCV, both minor-party and independent candidates would have better chances to win and be able to hold the major parties accountable and influence their direction.

Those now criticizing RCV as being too voter-centric are seeking to direct reform energy to fusion voting, whereby candidates can run with more than one party nomination. We see fusion voting as having relatively modest value that in no way replaces the value of RCV – most obviously, minor parties that engage in fusion nominations in the four states making some use of it rarely run their own candidates out of fear of spoiling the election. It also has a low viability ceiling, as it has proven unpopular with the elected leaders who need to pass and sustain it. Fusion voting has been banned in nearly every state, most recently with nearly unanimous votes in Delaware and South Carolina. Its most sustained use is in New York state, which has among the nation’s worst ballot access laws for minor parties and a notoriously opaque and corrupt governing system – and came close to ending fusion in 2019 when the state instead made it nearly impossible for any new party to earn the right to nominate candidates.

Still, while fusion voting is no replacement for RCV, we respect the energy behind it and support it when combined with RCV and when candidates are listed once (that is, with any nomination they receive listed following their name to avoid the confusion of the same candidate appearing multiple times on the ballot). We like how fusion voting allows minor parties to have public visibility and impact in elections where they haven’t recruited their own candidates.

Turning back to lessons from New Zealand, what grounded its reformers’ historic win three decades ago was the royal commission report that defined the viable path forward. We know that there is no comparable commission waiting in the wings to unite American reformers and recognize that our politically diverse states may end up with different reform paths. Still, we suggest translating New Zealand’s lesson to what might work here.

The urgent need and compelling opportunities for change are too great to leave that decision to anyone – not to us any more than anyone else. We propose instead having a substantive and inclusive review process designed to help participants identify the systems that provide impact within the boundaries of American political culture and institutions and are viable and scalable from local to national elections with a consistent ballot design. That process could also make recommendations on implementation and voter education for PRCV and any new system.

Such a process would improve dialogue, likely reduce sectarian tendencies and ideally result in a unity statement like the “ Good Systems Agreement” developed by British reformers who all back forms of PR. We don’t expect everyone to rally only around proportional RCV, but we do suspect it would avoid the kind of sectarian schisms that New Zealanders so successfully have avoided.

The bottom line is an exciting one for us. Three decades after we had our remarkable tour of a country on the cusp of reform history, we believe that transformative change can – and indeed, must – come to the United States. We look forward to joining others on that accelerating path in the coming decade

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift