Dr. Mascareñaz is a leader in the Cornerstone Project, a co-founder of The Open System Institute and chair of the Colorado Community College System State Board.

One of my clearest, earliest memories of talking about politics with my grandfather, who helped the IRS build its earliest computer systems in the 1960s, was asking him how he was voting. He said, “Everyone wants to make it about up here,” he said as gestured high above his head before pointing to the ground. “But the truth is that it’s all down here.” This was Thomas Mascareñaz’s version of “all politics is local” and, to me, essential guidance for a life of community building.

As a leader in The Cornerstone Project and a co-founder of The Open System Institute I've spent lots of time thinking and working at the intersections of education and civic engagement. I've seen firsthand how the democratic process unfolds at all levels — national, statewide, municipal and, crucially, in our schools. It is from this vantage point that I can say, without a shadow of a doubt, that the democracy reform movement will not succeed unless it acts decisively in the field of education.

In Colorado, where I'm working on rural outreach in support of a ballot initiative that would create open primaries with final-four general elections, voters consistently ask how these reforms will impact their local communities. They care about the education their children receive, the way schools are governed and how decisions are made. They understand, perhaps more intuitively than most, that the local school board race is not just another election — it's the foundation of our democratic society.

The current democracy reform movement, while well-intentioned and ambitious, could be missing a significant opportunity by focusing primarily on high-profile congressional and statewide races. By potentially overlooking the 81,000 school board elections (plus many hundreds more higher education races) across the country, the movement is neglecting a critical arena. This oversight could ultimately undermine the broader goals of the movement, as the foundation of our democracy is built in the very schools governed by these too often overlooked races.

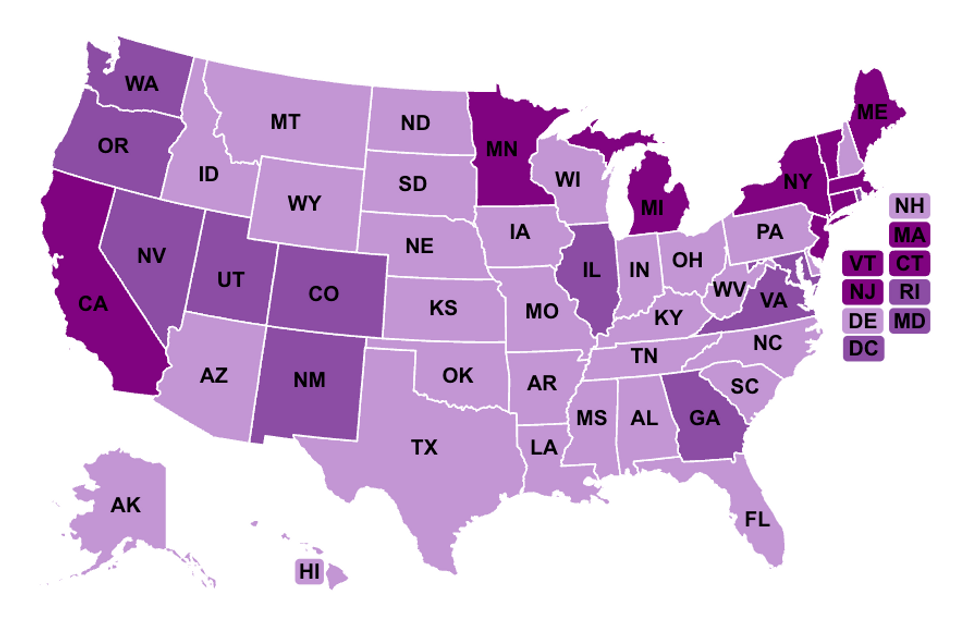

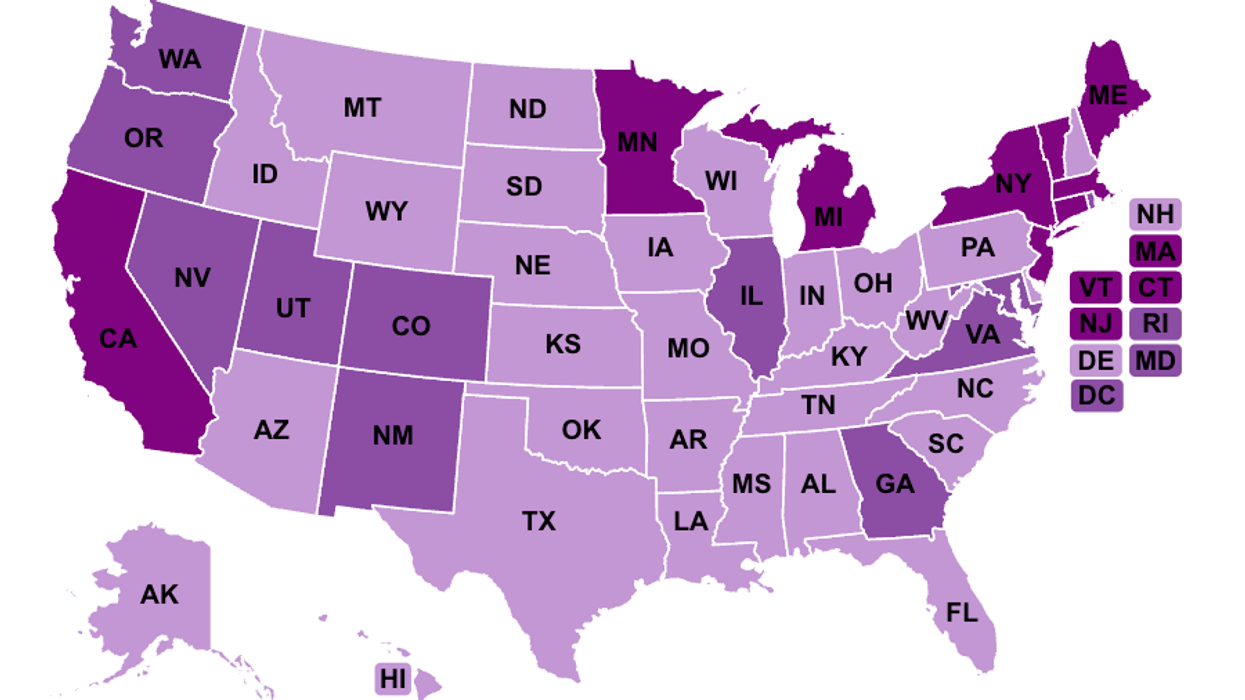

Therefore, we at Cornerstone are excited to announce the launch of the National EduDemocracy Landscape Map, a potentially first-of-its-kind research initiative designed to meet this critical moment for our democracy and education systems. The electoral and governance policies and practices we analyze as “EduRaces” and “EduDemocracy” are shorthand for the mechanics of school board races and higher education races that we believe have an opportunity to build democracy reform momentum.

This comprehensive resource brings together innovative democracy solutions and state-by-state analysis, offering a vital tool for leaders in both the education and democracy fields. This tool is essential at this moment in the democracy reform movement to take education seriously as a major lever for change — at the ground level.

From the global to the local

Recent research highlighted in the Journal of Democracy raises critical concerns about the current state of democracy across the globe, particularly in light of the challenges posed by recent election cycles. These findings emphasize that while elections remain a key pillar of democratic governance, they are increasingly susceptible to manipulation, polarization and erosion of public trust. These issues are not just theoretical — they have real, tangible impacts on how democracies function and people perceive their governments.

Research into school board elections further underscores the urgency of addressing these democratic vulnerabilities within the education sector. Voter turnout in school board races is notoriously low in some parts of the United States, with only 3 percent to 4 percent of voters participating in Newark, N.J., and just a few hundred people voting in Oklahoma City, a city of over 700,000 people. This lack of participation allows a small, unrepresentative portion of the electorate to make decisions that impact the education of future generations. We know that moving from odd year to even year or aligned elections matter significantly - dramatically increasing turnout and producing board members more likely to represent the views of their communities.

Additionally, studies such as those by Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz reveal a “demographic disconnect,” where voters in school board elections often do not reflect the diversity of the student population. For instance, in districts where the majority of students are racial and ethnic minorities, the majority of voters are often white, leading to governance that does not adequately address the needs of all students.

Moreover, the composition of school boards tends to be unrepresentative of the communities they serve, with most members being white men. In states like Arkansas, Missouri and Texas, over 60 percent of school board members are men, and 78 percent of all school board members identified as white. This lack of diversity can lead to governance that fails to consider the needs of all students, particularly those from minority backgrounds.

Compounding these issues is the trend toward increasing partisanship in school board elections. Traditionally nonpartisan, school board races in states like Florida, Arizona, and Kentucky are shifting toward partisan contests, which risks further polarizing these critical local elections. Students, the key user of our education system, are too sadly closed off and locked out from real and meaningful decision-making - not exactly practicing the democracy we preach.

This is all before we talk about the increasing use of school boards as tools for extremist politics and culture war issues, often exacerbated by low-turnout, at-large or plurality victories. As someone who has spent years working directly with superintendents and school boards I can say without a doubt these fractures prevent us from delivering on the promise of education.

EduRaces could be the front door to democracy renovation

The Cornerstone Project is an urgent call to action to address these issues — demanding that we take democracy innovation seriously within the education sector, as the future of our democratic society hinges on it.

I am an avid reader of Danielle Allen’s “ democracy renovation ” series in The Washington Post. I love her metaphor of renovating our democracy as one would renovate a house. If so, we may consider EduRaces the front door to the home. They are the door that most of our citizens see, use and open most often to access the power of our democracy locally.

There are some key reasons why education must be at the center of any serious effort to reform our democracy:

- The starting point for leaders: Education races are where so many political careers begin. From local school boards to state education boards, these positions are often the first step for aspiring public servants. By focusing democracy reforms on education, we can instill new democratic values and practices in the leaders who will go on to shape policy at all levels of government.

- Building the future of democracy: Our schools are where the next generation of voters and leaders is educated. If we want to ensure that our democracy remains strong, we must ensure that our education system is governed democratically and with the input of those it serves. The realization that few places have quality education to participate in education as a legal guarantee is shocking and contrary to the whole point. This is where the future of our democracy is built — brick by brick, lesson by lesson, election by election.

- Inclusive impact: Democracy reform, such as implementing ranked-choice voting and public financing, has been shown to benefit women and people of color by creating more equitable electoral conditions. Research indicates that these reforms can significantly increase the representation of diverse candidates, particularly in school board races, where women and people of color have historically been underrepresented. By leveling the playing field and reducing barriers to entry, these reforms could unlock a massive opportunity for more inclusive and representative school board governance.

- Proximity to voters' needs and concerns: Education is uniquely proximate to the needs and concerns of voters. Unlike other government functions, which may seem distant or abstract, the governance of schools directly impacts families, children and communities. Voters care deeply about the quality of education, the safety of their schools and the equity of opportunities provided to their children. Democracy and legal reforms in education can directly link voters to these changes in a way that statewide races might not. These are issues that democracy reforms must address if they are to resonate with the public.

- A testing ground for public systems: Education governance is where we can — and must — pressure test new ideas for building public systems. Whether it's implementing ranked-choice voting, public financing of education races or expanding voting rights to 16-year-olds, the education sector offers a controlled environment to trial these innovations before scaling them more broadly. If we can make democracy work better in our schools, we can make it work better everywhere.

These reforms are not just about improving education governance — they are about strengthening democracy as a whole. By addressing low voter turnout, lack of diversity, and increasing partisanship in school board elections, we can create a model for broader democratic reform that can be applied at all levels of government.

The call to action: The National EduDemocracy Landscape Map

By focusing on education, we can cultivate leaders, empower communities and ensure that democratic values are deeply rooted in the governance of our schools. The National EduDemocracy Landscape Map is a tool that the democracy and education movements cannot afford to ignore. It provides a comprehensive overview of where innovations are happening across the country and highlights where more work is needed.

The National EduDemocracy Landscape Map

The National EduDemocracy Landscape Map

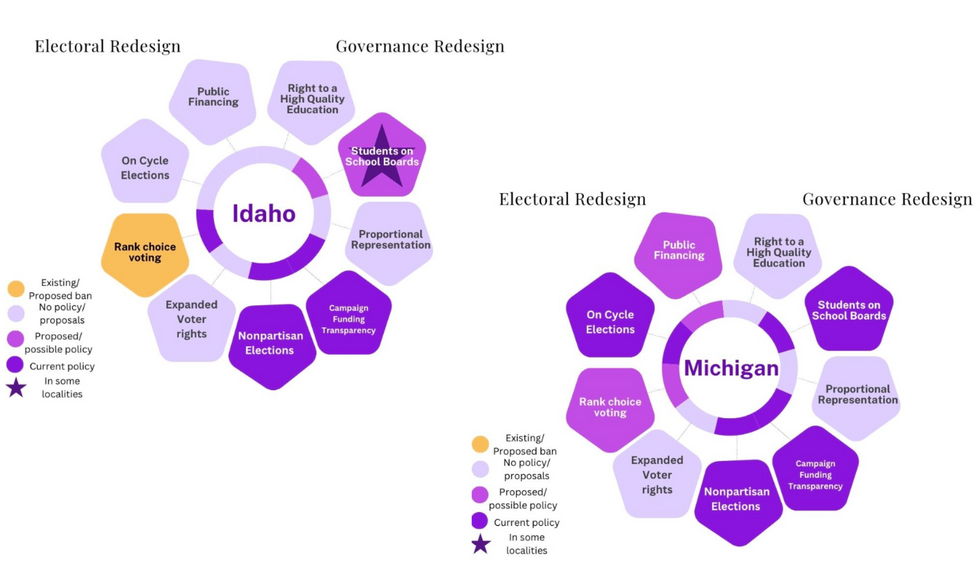

On the other hand, states such as Idaho and Louisiana demonstrate more limited adoption of these reforms, with many policies either in the proposal stage or only implemented in select localities. This contrast underscores the varying levels of commitment and readiness across the country to embrace democratic innovations in education.

Advocates within and across states can leverage the map and our state EduDemocracy analysis to guide their efforts. For those in states with more advanced reforms, the map can help identify best practices and successful strategies that can be replicated or expanded. In states where reforms are less developed, the map offers a clear picture of the gaps and challenges that need to be addressed, allowing advocates to prioritize initiatives that have the potential to gain traction.

Furthermore, by facilitating cross-state collaboration, we hope the map will enable advocates to build coalitions, share resources and amplify their impact, ensuring that even in states with limited progress, there is a coordinated and informed effort to push democracy reforms forward within the education sector.

The future of democracy starts in our schools

As many readers know, we are in an important inflection moment in our democracy. Working on our statewide measure in Colorado, I am reminded daily of the importance of local governance in shaping the future of our democracy. Just like my grandfather, voters want to know how these reforms will impact their lives, their communities and their children’s futures. To us, the answer is clear: If we want to build a more open, responsive and resilient democracy, we must start with education.

You may disagree with us about the impact and urgency to prioritize EduRaces in the democracy renovation space. Even if that’s the case, we would hope you would agree that these races are running with the flawed, closed models that are clearly hampering our ability to practice the full, open democracy that we all aspire to.

We urge the democracy field to get serious about EduRaces and for researchers, advocates and engaged citizens everywhere to dig into these important races. While of course banner statewide races are important, and municipal reforms matter significantly, education may be where we have the greatest opportunity to make a lasting difference — to build the front door to show all Americans democracy can work for them.

The Cornerstone Project is committed to leading this charge, and we invite everyone in the democracy movement to join us. Now is the time to harness the power of education to drive meaningful, structural change across our entire democracy.

The Cornerstone Project is a nonpartisan national education redesign and democracy renovation network aspiring to unrig the democratic infrastructure within education to reduce polarization, build a more just system, and unleash the potential for every learner to thrive by focusing on electoral redesign in Eduraces and governance reform.We bridge, learn, and act to support national, state and community leaders to transform Eduraces and education governance. The Cornerstone Project was founded by the Open Systems Institute, Seek Common Ground, and Education Civil Rights Now.

Why does the Trump family always get a pass?