Breslin is the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair of Political Science at Skidmore College and author of “A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation’s Fundamental Law.”

This is the latest in a series to assist American citizens on the bumpy road ahead this election year. By highlighting components, principles and stories of the Constitution, Breslin hopes to remind us that the American political experiment remains, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, the “most interesting in the world.”

America’s most influential abolitionists found themselves at odds over the proper way to interpret the Constitution. Their disagreement was profound. It reverberates today.

The scene is well-known. Nineteenth-century America is crippled by the formal institution of chattel slavery. Human bondage will both cause and hasten the onset of the country’s bloodiest-ever war. America’s original sin will stand alone as the foulest stain on the nation’s declaration that “all men are created equal” and its corresponding vow to “secure the blessings of liberty.” The United States is “a house divided against itself.”

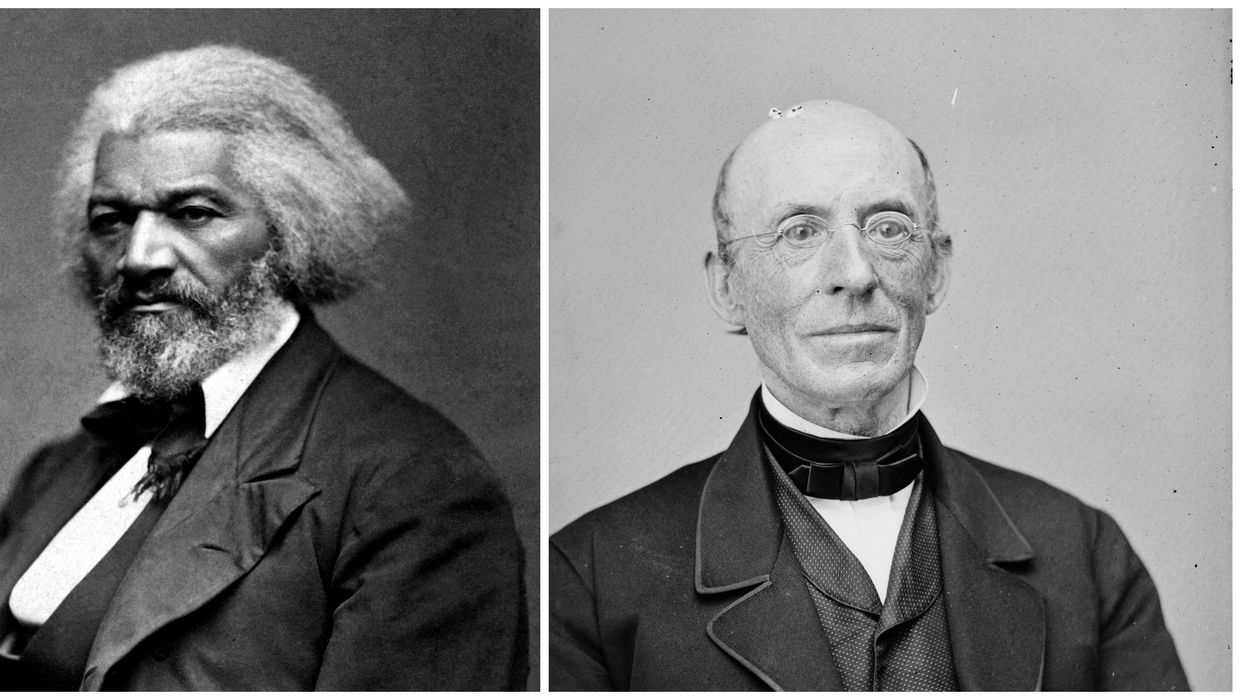

Enter Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Both are staunch abolitionists. They start out as close friends and comrades, especially during the late 1830s and into the 1840s when they toured together. They speak at meetings, gatherings and assemblies — a white man of the North and a Black, formerly enslaved man from below the Mason-Dixon line, sharing the stage. Eventually, though, the two will drift apart. Douglass will embark on a speaking circuit of the British Isles in 1845 and will return, 18 months later, to a frosty reception from his former touring companion.

Their initial fissure will emerge when Douglass starts his own abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, in direct competition with Garrison’s, The Liberator. The rift will widen when the former abandons pacifism in favor of violence and then outshines Garrison in Abraham Lincoln’s eyes. The fracture is complete when these historical giants offer starkly dissimilar images of America’s revered constitutional charter. It is those competing images, those dramatically unlike positions on the proper reading of the Constitution, that define the deterioration of this once great partnership. Unfortunately, they also help to explain the steep decline of America’s civic bond.

“What is the Constitution?” Douglass asked in 1860. “The American Constitution,” he answered, “is a written instrument full and complete in itself. No Court in America, no Congress, no President, can add a single word thereto, or take a single word thereto. It is a great national enactment done by the people, and can only be altered, amended, or added to by the people.”

For Douglass, the precise words of the Constitution were all that mattered. America’s fundamental law does not somehow absorb the interpretations and meanings imposed by such institutions as the Supreme Court. The charter stands alone and apart from those political officials charged with interpreting it. The Constitution’s words are clear; its pages tangible. We can touch it. We don’t need others to tell us what it says or, perhaps more critically, what its writers “intended.” Do we require some understanding of an author’s backstory, or of her motivations, when we read a novel? No, said Douglass. The same must then be true if we are reading the United States Constitution.

Garrison disagreed. He argued that context was the most crucial component of any constitution. Take slavery. Garrison recognized that the word slavery never appears in the Constitution. Doesn’t matter. The document was written by those who enslaved and by those who wanted to perpetuate the business of slavery. The Constitution therefore is a “compact with the devil” and an “agreement with hell.” One cannot understand the Constitution, the Bostonian insisted, without an awareness of the motivations of its drafters and the interpretations that have since furnished it with meaning. A novel, he held, is just a collection of words and sentences without the essential context of why and when it was written.

So, what does this abolitionists’ quarrel have to do with today’s politics? A good deal, actually. The way each of us understands the Constitution, I would argue, is the way we see the political world. A few illustrations may help, beginning with the most obvious: the right to privacy.

The word privacy, like slavery, does not appear anywhere in the Constitution or its 27 amendments. But does that omission mean that a woman can’t exercise her fundamental right to privacy? That the Constitution won’t protect her in securing a legal abortion? Douglass would say yes, unfortunately, it does mean that. The Constitution is “full and complete in itself” and if a safeguard for autonomous privacy is not enumerated, “no Court, no Congress, no President” can make it so.

Uh uh, says Garrison. The right to privacy is part and parcel of America’s constitutional story. He would no doubt cite Hamilton’s famous caution in “Federalist 84” that bills of rights are “unnecessary” and “even dangerous” as evidence that certain liberties — privacy among them — should be fiercely protected regardless of whether they are listed in the document. Unenumerated fundamental freedoms will emerge over time, Hamilton recognized; those that James Madison penned in 1789 cannot represent the entire set of “unalienable rights” that are “endowed by the Creator.” They just can’t. To think otherwise is to have one’s head in the sand. The Founders knew that men are fallible and, yes, even the Father of the Constitution might come up short with his list of liberties. How do we know that they knew this? The Ninth Amendment.

Now apply the competing stances taken by Douglass and Garrison to other political skirmishes. The Second Amendment mentions maintaining a “well-regulated militia” as the object for the people’s “right to keep and bear arms.” Can any citizen regardless of military service possess a gun? Article I empowers Congress to “lay and collect taxes,” “borrow money,” regulate interstate commerce” and “provide for the general welfare.” Does that mean it can charter a national bank? The Eighth Amendment prohibits the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishment.” Can the state impose the death penalty? On a person of color who, studies demonstrate, is far more likely to receive capital punishment if his victim is white? And how about Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which bars any “officer of the United States” from holding “any office under the United States” if they have “taken an oath to support the Constitution of the United States” and have engaged in “insurrection or rebellion against the same”? Does involvement in the events of Jan. 6, 2021, thus bar candidates from America’s highest office?

One’s answer depends on one’s view of the proper interpretive approach to the Constitution. We will never fully embrace a single method, like Douglass and Garrison never fully concurred, but it will certainly help our civic discourse if we at least understand each other’s positions. I truly believe that.

Thankfully, this story has a happy ending. Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison eventually reconciled. In 1873 they came together on the same stage to lend their considerable influence to the women’s suffrage movement. And though they would never again experience the depth of friendship they once enjoyed, they put aside their constitutional differences for a greater cause. The question is, can we?

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift