May is a senior research associate at Boise State University.

Thirteen top officials of the Trump administration violated the federal law known as the Hatch Act, which prohibits political campaigning while employed by the federal government. That's the conclusion of a federal government report issued by the special counsel, Henry Kerner.

The officials, including then-acting Secretary of Homeland Security Chad Wolf and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, "chose to use their official authority not for the legitimate functions of the government, but to promote the reelection of President Trump in violation of the law."

The Trump administration members were not the first federal employees to have crossed the line into prohibited political advocacy. Over the past few decades, government employees have been documented violating the Hatch Act in their offices, at meetings and in memos. And in a world awash in social media, it has become much easier for people to share their views about politics digitally.

But government employees work for the people of the United States. Paid with the tax dollars of Democrats and Republicans, they are supposed to work in the public interest, not use the power of the federal government to pursue partisan political causes.

Public dollars, public mission

The ideal of public employees as politically neutral is, at its core, driven by accountability.

For many government employees, the appearance of political impartiality is an overriding principle that governs their professional lives. Upholding this principle can even cause them to sacrifice their own electoral influence outside of the office.

I am a scholar of public policy and administration, and my research indicates that many would rather not vote in a party's primary election, where they would be required to publicly state what party they belong to.

Where is the line between professional standards and political speech?

Public servants, the argument goes, should be neutral and concerned only with implementing public policy that is decided by elected officials. This principle has driven the field of public administration for more than 100 years.

Passed in 1939, the Hatch Act prohibits federal employees from running for partisan office, encouraging subordinates to engage in political activity, soliciting political contributions or engaging in political activity while on duty. It does not prohibit affiliating with a political party, discussing politics or attending fundraisers.

The Hatch Act generally only applies to federal employees. It does not apply to the president, vice president or Cabinet appointments. It can also cover state and local government employees, if their work is at least partially funded by federal dollars. Several states, such as Minnesota, North Carolina and Ohio, have additional laws that can further restrict the political activity of public employees, even if their positions aren't federally funded.

From 2010 through 2016, the Office of the Special Counsel, or OSC, which investigates Hatch Act violations, received an average of 315 Hatch Act complaints per year, which resulted in an average of 102 warning letters per year. An average of nine employees per year have resigned from their positions in response.

Some recent examples of Hatch Act violations include asking others to "help our candidates" and pressuring supervisors to allow employees time off in order to campaign for their union's preferred candidate. Others coordinated partisan elections using taxpayer-funded resources. Even retweeting a post from the president of the United States on social media constituted a violation.

From patronage to neutrality, via assassination

During the early years of the United States, the federal government operated under a system known as "patronage."

Under that system, a newly elected president could replace federal employees with a person of their choosing. Often, they chose only from among their supporters, campaign workers and friends. This was especially true if the presidency changed political parties.

The public bureaucracy was constantly changing, and few officials were around long enough to develop institutional memory. In addition, patronage led to the appointment of people who were not qualified for the positions they got, leaving the government inefficient and the public dissatisfied.

President Woodrow Wilson, prior to his presidency, and Frank Goodnow, writing separately at the end of the 19th century, first articulated the theory that there should be a wall between elected officials who set public policy and the professional staff charged with implementing that policy.

A professional class of government employees was not the tradition of the United States at that time, and the public had to be convinced of its virtue. Wilson's essay tried to help the wider population understand why civil service reforms were necessary.

There was another event that also helped move government employment from patronage to professionalism. In 1881, a man who felt he had been unfairly passed over for a patronage job shot and killed President James Garfield. This assassination helped highlight the problems of the patronage system and led to the passage of the Pendleton Act in 1883. That legislation instituted a merit-based civil service system that remains largely in place today.

Under the system instituted in 1883, only the top levels of federal agencies can be replaced by patronage appointments – friends, supporters and allies of the new administration. The remaining levels of rank-and-file staff are expected to be nonpartisan professionals. In many respects, the Hatch Act can be seen as an outgrowth of this ideal.

A 'fanciful' distinction

The boundary between politics and civil service employees is not necessarily easy to see or maintain. Scholars have wrestled with whether government employees, charged with implementing vague public policy, can really be separated entirely from political concerns.

In fact, some scholars have rejected the separation as fanciful. In an important debate between preeminent public administration scholar Dwight Waldo and Nobel Prize-winning economist Herbert Simon, Waldo argued that when some decision-making is left to administrators, an administrator's own politics will influence those decisions. In short, public employees are not actually neutral. Simon, on the other hand, argued that efficient government required that administrative decisions should emphasize objective facts and not be influenced by a public employee's personal values.

While most public administration scholars have moved beyond debate about the dichotomy itself, public employees still have to grapple with their proper role. And they do so as they work for elected policymakers, who themselves still think that they are the only ones who should drive what all levels of government do.

Neutrality not getting easier

For over a century, public employees have generally subscribed to an ethos that theirs is a professional role separated from the daily political grind. In the modern era, it takes far more discipline to maintain that separation. And it does not appear to be getting any easier.

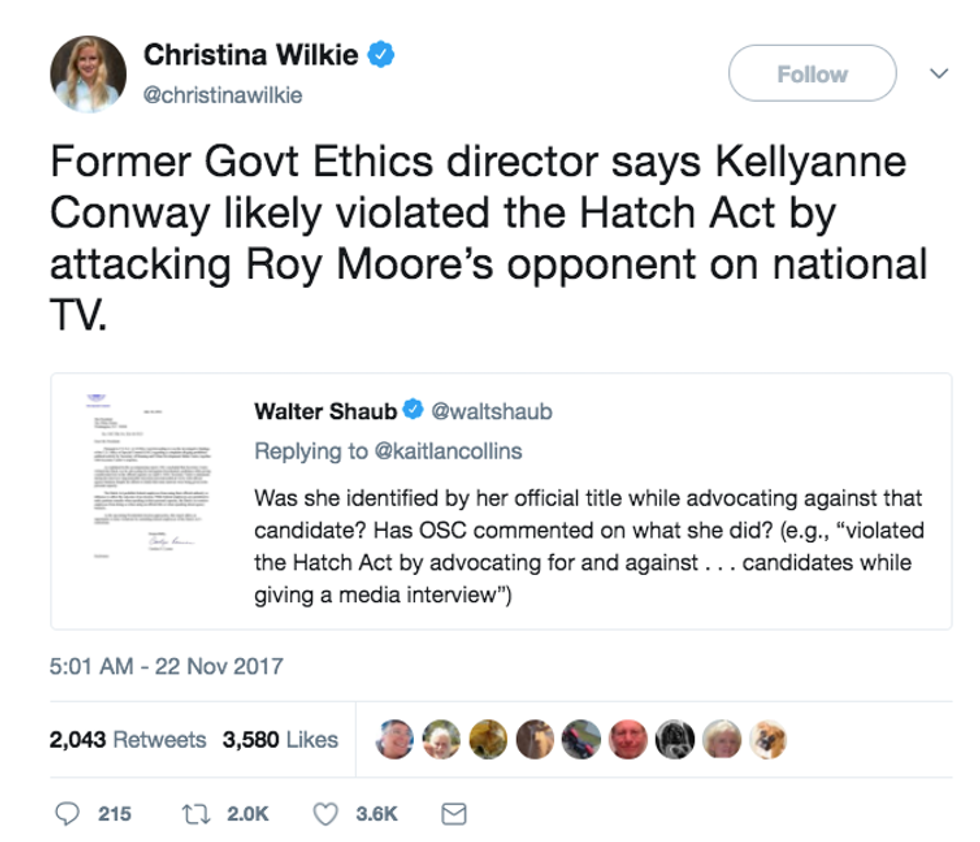

CNBC reporter Christina Wilkie's tweet about Kellyanne Conway's attack on a Democratic political candidate; Conway was found to have violated the Hatch Act. Twitter

CNBC reporter Christina Wilkie's tweet about Kellyanne Conway's attack on a Democratic political candidate; Conway was found to have violated the Hatch Act. Twitter

In 2015, the Hatch Act was clarified to prohibit federal employees from, among other things, liking or retweeting a political candidate while on the job, even during break time. Some in sensitive positions, like law enforcement or intelligence, are even prohibited from doing so during their off-hours.

Despite that attempt at clarity, in today's hyperpartisan climate, social media and 24-hour connectivity have helped blur the line between a public employee acting in their official capacity and their private life.

The Trump administration officials' violations help remind us that the line between political activity and professional neutrality still exists for federal employees. And in this increasingly connected world, the opportunities to fall short are plentiful.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()