The very course of American history is shifting with the formalized launch of an impeachment inquiry against President Trump. And for those who view democracy as broken, and well beyond all the recently alleged abuses of executive power, one important undercurrent is captured by this question:

Can Congress use the proceedings to recalibrate the balance of power, reclaiming even a bit of the muscle it's allowed to atrophy to the benefit of presidents for so long — and maybe even end up boosting its abysmal public reputation as dysfunctional and polarized?

It's a big reach. But the ingredients are there for Capitol Hill to reap lasting institutional benefit from the coming drama, and for American democracy to be better off at the end, no matter what the outcome for Trump.

Looking to emulate aspects of the last impeachment is a place to start.

To be sure, the prosecution of President Bill Clinton for trying to hide his affair with Monica Lewinski is widely viewed now as a low point in the modern history of petty politicized warfare at the Capitol. But it was also marked by notable bursts of bipartisanship and seriousness of purpose at the most important moments, even when the legal and constitutional arguments were a bit sloppy.

And, while the ideological divides in both the House and the Senate are way sharper than two decades ago, there's just enough centrism left in both places to make some crossover voting possible — which would be essential if Congress is to gain credibility from what's sure to be an incredibly bitter time ahead.

Tempering a disdain for Clinton

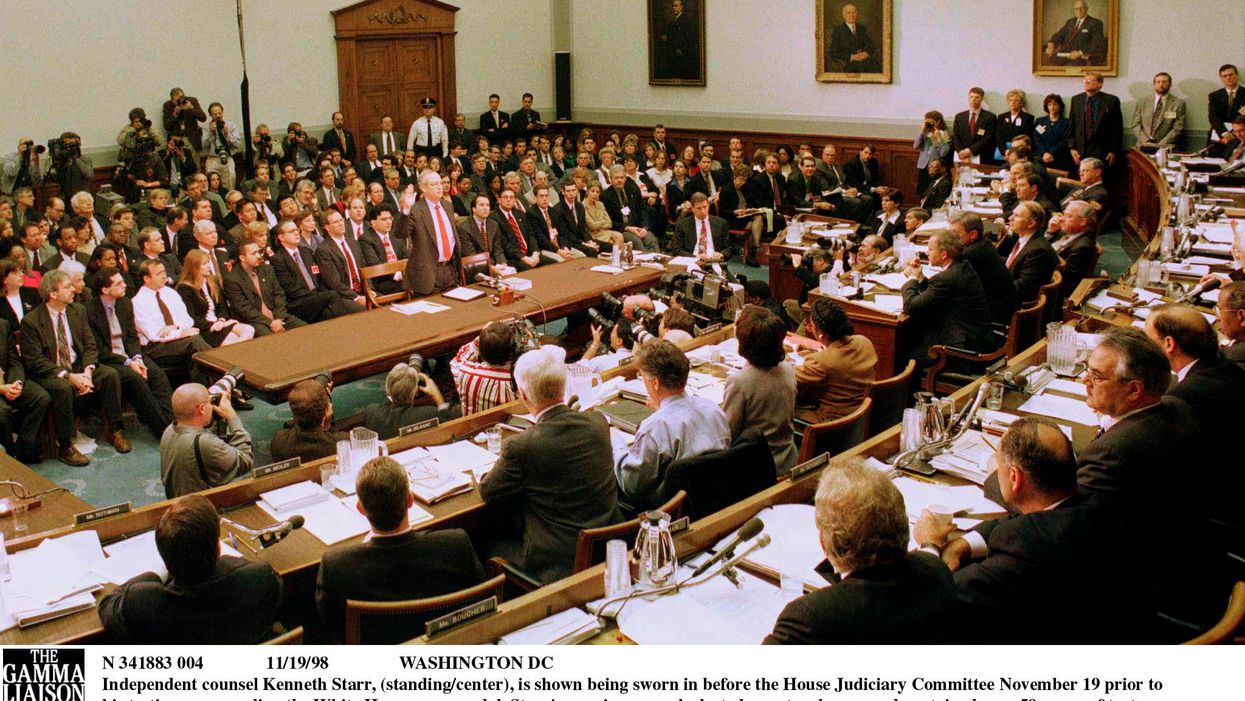

In September 1998, House Democrats voted 2-to-1 in favor of making entirely public the independent counsel's lurid recounting of the sexual encounters between a president from their own party and a onetime White House intern. More relevant to today, one month later 31 of them joined all the majority Republicans in voting to turn the Judiciary Committee's consideration of Ken Starr's report into a formal impeachment investigation.

(In February 1974, the House vote was 410-4 for the resolution formally authorizing the Judiciary panel's probe of President Richard Nixon as an impeachment inquiry.)

But Speaker Nancy Pelosi's declaration this week, that investigations by six committees now constitute another such formal inquiry, has not been followed by any plans for a similar vote putting the whole House behind that authorization.

Several legal scholars have said such a ratification would put the House on a much stronger footing in the courts, because precedents suggest that lawmakers considering impeachment have the strongest possible claim to documents and witness testimony despite a president's objections.

So a vote ratifying Pelosi's unilateral move would be good in the long term for boosting congressional oversight authority — and therefore would be theoretically attractive to at least a handful of veteran, and electorally safe, Republicans with an eye toward holding some future Democratic president accountable.

Speed and focus

After the 1998 authorization, it was just 10 weeks before articles of impeachment were debated on the House floor — an intensely compressed timetable made possible by the GOP consensus to fix entirely on the Starr report's allegations and not at all on the myriad other things about Clinton that made them furious.

The Democratic leadership seems inclined to follow that approach now. They're hoping that by focusing exclusively on one newly rich vein, Trump's relationship with Ukraine, they can move toward a House vote "expeditiously."

Wrapping this up before the 2020 campaign becomes wholly consuming could prove extremely difficult, however. That is, unless during the next two weeks of congressional recess the fractured Democratic Caucus is persuaded by the folks back home to forget about pursuing an exhaustive impeachment agenda that covers everything from Trump's tax returns and real estate dealings to his myriad public falsehoods and alleged obstructions of justice.

Given how solid the wall of House Republican support for the president has been so far, there's not much reason to expect it to crumble before an impeachment floor vote. But it could crack at the margins, especially if some GOP members heading toward retirement (13 of them at the moment) feel liberated to vote their conscience.

Conversely, at least a few of the 31 Democrats representing districts Trump carried in 2016 may feel compelled, in the name of political survival, to vote "no" regardless of what high crimes and misdemeanors are alleged.

The December 1998 votes were portrayed by both sides as an existential test of party loyalty, and yet 10 members of the rank-and-file defied that pressure — an equal number of conservative Democrats voting for impeachment as moderate Republicans voting against. Even that small roster of lawmakers going against the grain helped give the indictment of Clinton an aura of sobriety and legitimacy.

When all 100 senators agreed

That sense of seriousness threatened to unravel immediately thereafter, though. That's because at that time, as now, a Senate trial seemed so foreordained to end in acquittal as to make it questionable why senators should spend time going through the motions.

Since there's no explicit constitutional requirement for a trial, no procedural recourse prevents Majority Leader Mitch McConnell from deciding there wouldn't be one. The polarized public sentiment, however, would be at least as intense as when the Kentucky Republican decreed a Supreme Court vacancy would remain for the final quarter of President Obama's second term.

And so, if he has in mind the Senate's faltering reputation — as well as the futures of Senate GOP colleagues at risk in 2020 — McConnell may turn to the playbook developed by the floor leaders of two decades ago. How Republican Trent Lott of Mississippi and Democrat Tom Daschle of South Dakota steered the Senate through the first impeachment trial in 131 years remains a highlight of both their careers. Their careful and collaborative mix of political practicality and institutional reverence leaving neither party altogether happy nor totally outraged by the process.

For starters, Lott and Daschle got all 100 senators (you read that right) to vote for the rules of the trial, which combined the GOP prosecutors' demand for witnesses with the Democratic defense's insistence on tightly controlled subpoenas and rules of evidence.

Nine days later, they countenanced a vote on whether to dismiss the charges — knowing full well that the motion's defeat, 44-56, would drain the trial of any remaining drama by showing definitively that a two-thirds majority to remove Clinton from office was not going to materialize. (Eleven senators would have had to reverse position to produce 67 votes for conviction.)

It took two more weeks, but in the end the historic roll calls of February 1999 were nowhere close. All 45 Democrats voted for acquittal on both counts. Ten Republicans joined them in deciding the president did not commit perjury. Five of those Republicans — all from states Clinton carried in both his elections — also voted to acquit him on a broader obstruction of justice charge.

Back to work

And then Congress and Clinton swiftly moved on. All sides concluded their next political reward lay in showing they could return to legislative functionality with relative ease after living through the paroxysms of impeachment. The rest of the year featured a budget deal, a rewrite of banking law, new health insurance protections for disabled workers, an expansion of federal aid to education, a plan to pay back $1 billion in overdue United Nations dues, preparations in case computers choked on Y2K — even a salary increase for the next president.

It is possible the climax of a Trump trial could be something of a twist on that same narrative: He is acquitted after a trial that's substantive enough to satisfy his opponents but quick enough to mollify his allies — with all or almost all the 47 Democrats voting to convict and being joined by half a dozen or so GOP senators in tough races for re-election.

And it is possible the coming months provide a jolt of belief in the notion that Congress can rise above historically low baseline expectations at the big moments — and maybe even deserve some credit along the way for acting responsibly even while behaving passionately.

When the Capitol's occupants decide that being on their best behavior is in their collectively enlightened self-interest, they can still behave pretty well.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift