In a matter of weeks, President Trump has thrown into question the future of a decades-old bedrock of open government: Independent watchdogs working inside federal agencies to find wrongdoers and root out waste.

But his recent spate of inspector general firings, combined with public threats and not-so-subtle efforts to undercut the authority of many others in those jobs, are only the most serious actions of a president who came to office as a skeptic but is now seeking re-election as a full-throated opponent of such independent oversight.

Trump's accelerating antagonism is more than another sign of how emphatically he's abandoned his "drain the swamp" 2016 campaign mantra. It's also drawn unusual campaign season antagonism from several influential Republicans in Congress, who last week launched legislation that would make it tougher for Trump to dismiss inspectors general and restrict who he could name as a government watchdog.

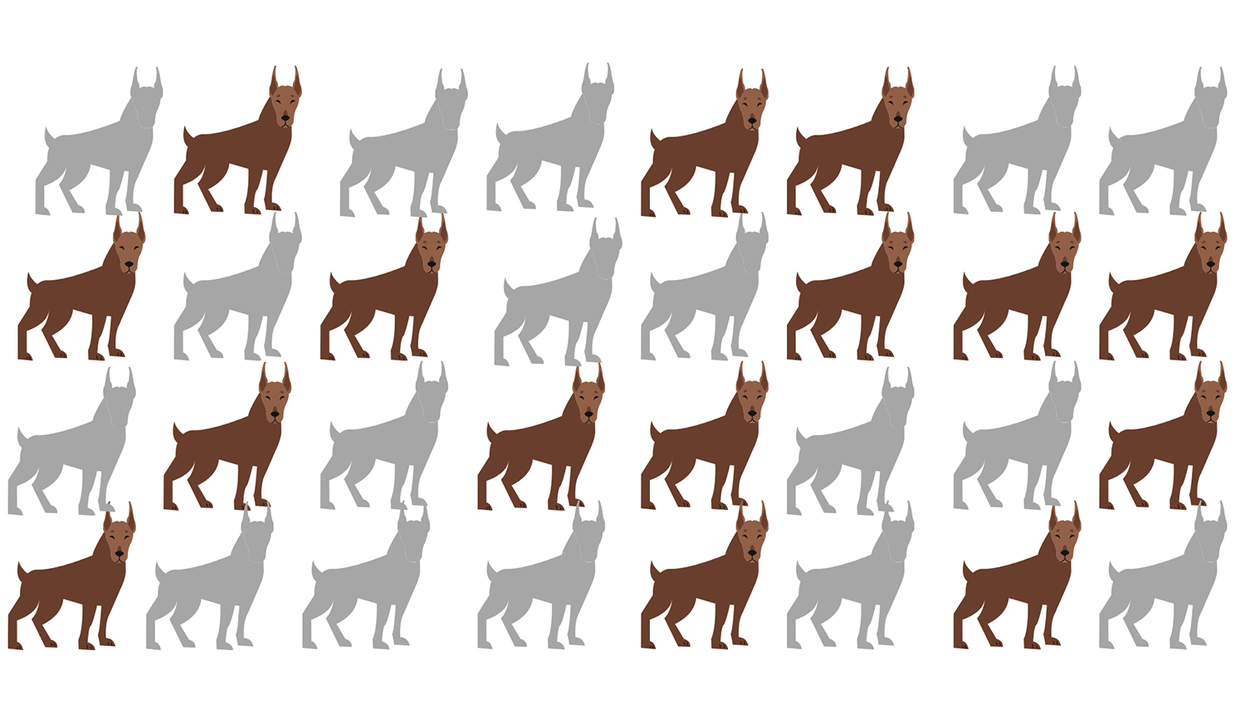

Since Trump arrived at the White House, the leadership of 28 of the 73 inspectors general offices in the government (two out of every five) has changed at least once. And at least one such replacement has happened at 17 of the 32 agencies or departments (more than half) where the president has the authority to directly appoint the inspector general.

Eleven agencies — including the CIA, the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services — are now operating with acting, not permanent IGs. These positions have been vacant for a combined total of more than 26 years.

The Department of Defense, which has a budget of more than $700 billion this year (about $2 billion per day), has not had a permanent inspector general since the seventh year of the Obama administration.

The problem with having a bunch of acting inspectors general instead of permanent ones was addressed in a recent report from the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan group that investigates misconduct and conflicts of interest by federal officials — acting as an outsider watchdog over the work of federal watchdogs. People named to these jobs only on an interim basis, the group concluded, are "put in the position where the thoroughness or aggressiveness of their work can weaken their chance of being appointed to the permanent slot."

What has thrust the usually behind-the-scenes world of inspectors general into the forefront was a remarkable rapid-fire series of actions in the past three months:

April 3: Trump told Congress he intended to fire Michael Atkinson as inspector general for the intelligence community. Atkinson got on the president's bad side for doing his job — passing up the chain of command the whistleblower complaint, which ended up spurring Trump's impeachment, about the president soliciting Ukraine's help in digging up dirt on Hunter Biden, the son of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, who worked for a Ukrainian company when his father was vice president.

April 6: Trump lambasted Christi Grimm, acting inspector general in the Department of Health and Human Services, after her staff issued a report about a severe shortage of testing kits for the coronavirus, delays in getting test results and shortages of masks and other equipment at hospitals. On May 1, he moved to replace Grimm by announcing her successor.

April 7: Trump removed Glenn Fine, acting IG at the Pentagon, who had also been chosen by his fellow IGs just days earlier to oversee the work of the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, an independent oversight panel created by Congress to ensure the $2.2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package enacted in March was not misspent.

May 15: Trump announces his intent to fire Steve Linick, inspector general for the State Department. Linick was investigating allegations of misbehavior by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, among other things.

May 16: Trump fired the acting Transportation Department inspector general, Mitch Behm. He had been selected for the special economics stimulus oversight panel and also was investigating Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao, the wife of Senate GOP Leader Mitch McConnell.

June 11: Leaders of the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee sent a letter to House and Senate leaders warning that administration officials were arguing that more than $1 trillion of the money was exempt from oversight.

It was less than two years ago, on the 40th anniversary of the original inspectors general law, that IGs were being celebrated and the benefits of their oversight were being quantified and praised.

Michael Horowitz, inspector general for the Department of Justice and the chairman of the IGs council, reported that in 2016, then the most recent year with complete data available, his colleagues saved taxpayers more than $45 billion, engineered more than 4,800 successful criminal prosecutions and drove more than 4,300 disciplinary actions.

Overall, he boasted, every dollar spent on the work of IGs saved $17. And that return on investment seems to be continuing, with more than $20 billion in potential savings identified by the watchdogs so far this year.

Despite this record of success, the Trump administration has also attempted to undercut the IGs by slashing many of their budgets — in a seemingly ad hoc way, and largely without success.

For the coming year, for example, he's proposed cutting the IG budgets at six of the 16 biggest agencies, including a 7 percent reduction (to $178 million) for the Department of Homeland Security watchdog. But he's proposed increasing spending on IGs at all the rest, including a 13 percent boost (to $90 million) at HHS.

Delays and GOP pushback

Congress shares some responsibility for the current weaknesses in the overnight system, however, by moving slowly to fill vacancies and fill the loopholes in the law Trump has exploited to hobble the inspector general system.

The president has picked people for half the 16 inspector general vacancies where the president makes the nomination — but those eight have been waiting an average of 14 weeks for confirmation by a GOP-majority Senate focused much more intently on filling open judgeships.

Only three IG nominees have been vetted by committee and need only a vote on the Senate floor.

Critics point out that five of them have no experience as inspectors general or in another government oversight role.

Faced with mounting pressure from good government advocates, Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa introduced legislation last week to strengthen protections for the inspectors general.

The longest-serving current Senate Republican has been known since the 1980s as a champion of vigorous government oversight, and he drafted the bill while holding up a pair of Trump nominees for senior national security jobs for two weeks — until the White House offered formal justifications for the Atkinson and Linick firings.

Grassley noted the IG law requires the president to provide Congress with advance notice of such dismissals along with a reasoning.

In introducing the legislation, Grassley tried to put a bipartisan spin on his cause by noting President Barack Obama violated the law by firing an inspector general without explanation.

He also found four other Republicans along with five Democrats to sign on to the bill from the start — a highly unusual show of bipartisanship in today's Senate, especially in an election year. The GOP cosponsors are Susan Collins of Maine, Mitt Romney of Utah, Rob Portman of Ohio and James Lankford of Oklahoma.

Grassley said the measure would beef up the notification mandate by making presidents include a "substantive rationale, including detailed and case-specific reasons," for every IG firing

His bill attempts to address concerns that Trump has named unqualified people as temporary inspectors general by requiring acting IGs come from the senior ranks of the watchdog community. To ward off any chickens guarding hen houses, the bill would bar senior agency officials from even acting temporarily as inspectors general. Other language is designed to safeguard ongoing investigations during IG transitions.

"Congress designed inspectors general to shine a bright light on waste, fraud and abuse through the federal bureaucracy," he said on the Senate floor when introducing the bill. "So IGs are the original swamp drainers."

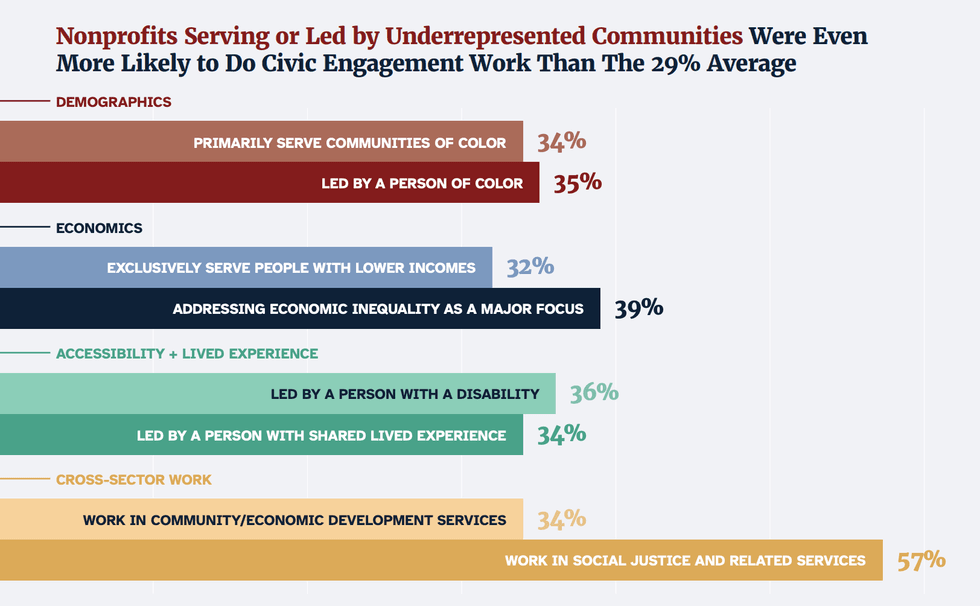

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift