Pearl is a clinical professor of plastic surgery at the Stanford University School of Medicine and is on the faculty of the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is a former CEO of The Permanente Medical Group.

As lawmakers and other Americans grapple with rising inflation, which reached a 40-year high this month, many conversations about the future of the economy now center on the cost of health care. In the past, legislative attempts to curb health care spending have primarily focused on prices, payers, and providing health care to the uninsured and been subject to the usual partisanship that dooms most legislation to failure.

A focus by legislators instead on technology solutions might lessen the partisan divide and result in meaningful legislation.

In the 21stcentury, a vast majority of U.S. industries have used information technology to cut costs — as well as increase access and improve quality. Health care is a notable exception.

For decades, U.S. medical costs have risen faster than inflation — annual spending now eclipses $4 trillion. What’s more, accessing medical care is both time consuming and burdensome for many patients. Meanwhile, U.S. health care lags other wealthy nations in almost every measure of quality, including life expectancy and childhood mortality.

Modern technologies could help solve these problems but the threat to the status of the doctor is certainly a reason for many of them to be reticent.

The expression “Lay hands on the sick and they will recover” dates back to biblical times, when the hands of healers were believed to have curative powers. In the millennia that followed, physicians followed that tradition.

By the 18th century, doctors took great pride in their ability to assess a patient’s temperature using only their hands. This skill took years of training to master, helped distinguish doctors as experts and boosted the prestige of the entire profession.

Around that same time, Daniel Fahrenheit invented a new device called the thermometer, which could measure body temperature within one-tenth of a degree.

What happened next was a seminal moment in medical history. Rather than welcoming Fahrenheit’s technological wonder with open arms, doctors dismissed it as bulky, impractical and painfully slow to calibrate. Indeed, the first-gen version was all those things. But those design flaws don’t explain why physicians ignored — and outright denied — the thermometer’s potential to help patients. To preserve their status, doctors spent the next 130 years fighting to keep the thermometer out of the exam room.

Ever since the thermometer’s debut, doctors have given preference to technologies that boost their reputation, and they’ve rejected tech that threatens their prestige.

This focus must change.

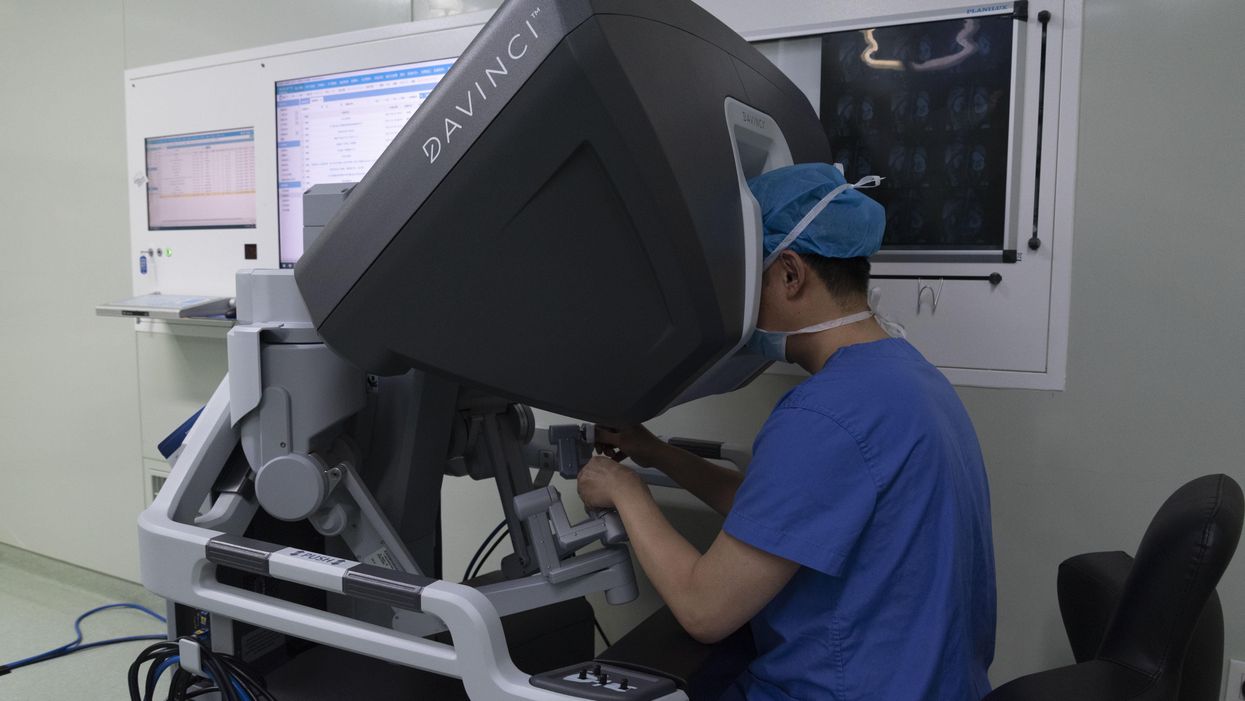

Consider the industry-wide obsession with operative robots. These multimillion-dollar machines look like space-aged command centers with doctors (and only doctors) sitting in the captain’s chair, directing the movements of two large robotic arms. Just one look and it’s clear: These machines are incredibly cool. The surgeons who use them are seen as cutting edge. Medical journals now overflow with descriptions of new and interesting applications for them. That’s why, according to a recent survey, the surgical robotics market is now projected to grow by 42 percent annually over the next decade.

Here’s the problem: Independent research from 39 clinical studies has determined that robot-assisted surgeries have only modest clinical advantages over other approaches. They fail to extend life expectancy or significantly reduce surgical complications.

Looking objectively at the impact this technology has on patients, the operative robot is a dud. But for the physicians using it, the machine is a megahit.

Good for patients, bad for physicians?

In sharp contrast to surgical robotics, there are several modern technologies that could positively and powerfully transform patient care. Yet, most generate lukewarm to negative reactions from physicians. Here are two examples.

Telemedicine

Prior to the pandemic, only one in 10 patients had experienced a virtual visit with a doctor. That changed at the onset of Covid-19, when physicians’ offices were forced to close.

Suddenly, telehealth accounted for 70 percent of all visits and — to the surprise of doctors and patients alike — the experience was resoundingly positive. Physicians resolved patient problems faster and more effectively than before. Patients, meanwhile, enjoyed the added convenience and most (75 percent) expressed satisfaction with virtual care.

Yet, in the months that followed, telemedicine usage receded to almost pre-pandemic levels, now accounting for just over 10 percent of patient visits (not including virtual mental health).

The problem isn’t the technology. It’s what the technology represents. Telehealth constitutes a threat to the physician’s office, a place where the prestige of the doctor is on full display. Doctors take great pride in seeing their names embossed on the front door bold letters. Even the waiting room communicates the importance of the doctor’s time.

With telemedicine, these status symbols are removed from the doctor-patient experience. And so, even though telemedicine offers patients greater convenience with no evidence of quality issues, doctors undervalue and underutilize it. As a result, won’t find journal articles in which clinicians push the boundaries of virtual health care as we see with the surgical robot.

AI and data analytics

Computing speeds continue to double every couple of years. It’s a phenomenon known as Moore’s Law, and it means that tools like artificial intelligence and data analytics are becoming smarter and more capable of transforming health care delivery.

Already, AI has been shown to interpret certain X-ray studies ( mammograms and pneumonia) more accurately than skilled radiologists. In the future, computers with machine-learning capabilities have the potential to make diagnostic readings of pixels better and faster than humans.

Meanwhile, data analytics (which inform evidence-based algorithms) have the power to dramatically improve physician performance. When doctors consistently follow science-based guidelines, they achieve far better clinical outcomes than on their own. With these tools, physicians have the opportunity to lower mortality rates from heart attacks, strokes and cancer by double digits. But, as with the thermometers of yore, you won’t find physicians clamoring for them.

Instead, you’ll hear doctors from every specialty denounce the use of computerized checklists and algorithmic solutions as “cookbook medicine.” Medicine, they say, isn’t a recipe to be followed. They argue that data analytics and AI will turn every doctor average, ignoring the fact that the “new average” will be vastly better than today’s mediocre outcomes. No matter how much better the results, technologies that tell doctors what to do are seen as a threat to the profession. Invariably, physicians will reject them.

Selecting the best tech with forced transparency

Transparency is the best and first step toward breaking this outdated rule of technology in health care. Here’s how that might look.

In partnership with an independent and highly respected agency like the National Institutes of Health, scientists could analyze the scientific merits of various health care technologies. The list might include the surgical robot, along with proton-beam accelerators, wearable heart monitors, PET scanners, telemedicine, AI and chatbots for self-diagnosis.

The researchers would review published data, analyze each technology and publish a cost-benefit rating, similar to what you’d find in Consumers Reports.

Though this exploratory body wouldn’t have regulatory power — the way the FDA has authority over drug approvals — it would nonetheless serve an important function. This process would provide an unbiased evaluation of the most promising tools for patients and could serve as a basis for legislative action.

If our nation wants higher quality and greater affordability from health care, we will need to measure technology by its impact on patients, not its impact on the status of doctors.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift